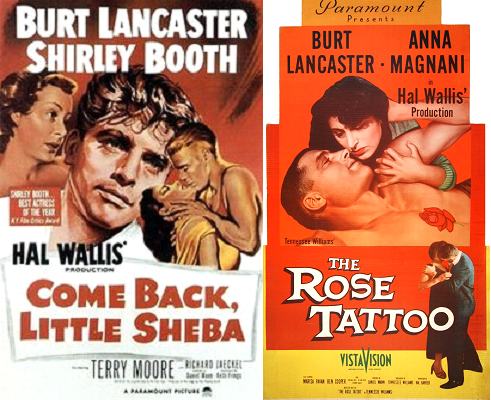

Come Back, Little Sheba (1952) and The Rose Tattoo (1955)

Toronto Film Society presented Come Back, Little Sheba (1952) on Monday, October 8, 1986 in a double bill with The Rose Tattoo (1955) as part of the Season 39 Monday Evening Film Buffs Series “B”, Programme 1.

Come Back, Little Sheba (1952)

Production Company: A Hal B. Wallis Production presented by Paramount. Producer: Hal B. Wallis. Director: Daniel Mann. Screenplay: Ketti Frings, from the play by William Inge. Photography: James Wong Howe. Editor: Warren Low. Music: Franz Waxman. Art Directors: Hal Pereira, Henry Bumstead. Sets: Sam Comer, Russ Dowd.

Cast: Burt Lancaster (Doc Delaney), Shirley Booth (Lola Delaney), Terry Moore (Marie Buckholder), Richard Jaeckel (Turk Fisher), Philip Ober (Ed Anderson), Liz Golm (Mrs. Coffman), Walter Kelley (Bruce), Edwin Max (Elmo Huston).

The Rose Tattoo (1955)

Production Company: A Hal B. Wallis Production presented by Paramount. Producer: Hal B. Wallis. Director: Daniel Man. Screenplay: Tennessee Williams, fro his play; adaptation by Hal Kanter. Photography: James Wong Howe. Editor: Warren Low. Music: Alex North. Art Direction: Hal Pereira and Tambi Larsen. Set Decoration: Sam Comer, Arthur Krams.

Cast: Anna Magnani (Serafina Delle Rose), Burt Lancaster (Alvaro Mangiacavallo), Marisa Pavan (Rosa Delle Rose), Ben Cooper (Jack Hunter), Virginia Grey (Estelle Hohengarten), Jo Van Fleet (Bessie), Sandro Giglio (Father De Leo), Mimi Aguglia (Assunta), Florence Sundstrom (Flora), Dorrit Kelton (Schoolteacher).

Tonight’s double feature brings together two screen adaptations of hit Broadway plays of the 1950s. Both films, directed by their original stage director, Daniel Mann, provided Academy Award-winning roles for their leading actresses, both of them co-starring with Burt Lancaster in two of his most off-beat assignments. Both films share as well the same cameraman, the same editor, and the same art director. The films possess, as a result, a similar look and style which should at least partly be accredited to the producer who assembled this gifted team of craftsmen. Hal Wallis was one of those few Hollywood producers of the golden Studio Years who against all odds managed to maintain his independence–and individuality. Come Back, Little Sheba and The Rose Tattoo were among his favourite projects, he tells us in his autobiography, Starmaker.

In Come Back, Little Sheba, Shirley Booth (born in 1907) was repeating the role she had most successfully created in the Theatre Guild production on Broadway. For this, her first film, she received instant and unanimous rave reviews for her performance as a middle-class housewife whom the various critics described as “dowdy”, “slovenly”, “immature”, “lazy”, “earnestly pleasant”, “pathetic”, “foolish”, and “a dull and bulky shadow of a 1920s vamp”. While the picture clearly belonged to her, most critics allowed that the relatively young Lancaster (born in 1913) was a worthy partner as her chiropractor husband who had given up his medical studies when forced to marry her many years before. The film centres on the husband’s violent return to a supposedly controlled drinking problem when the presence of an attractive roomer arouses dormant desires in his aging body. Lancaster had to beg Wallis to let him play this part which seemed so far removed from his tough-guy or athletic screen persona of the period. He would be replacing Sidney Blackmer from the Broadway production. Wallis recounts the problem–and its solution.

“It was difficult for this huge virile man to look like a weakling. We dressed Burt in a sloppy, shapeless button-up sweater, padded his figure to flab out his trim waistline, and gave him baggy trousers that made him look hip-heavy. He wore pale makeup over a stubble of beard, but we still had a problem hiding his magnificent physique. We made him stoop a little, hollow his chest, and walk with a slow scuffle in bedroom slippers.”

The script of Sheba remained largely faithful to the stage production’s, although it did open up the action occasionally to locations other than the couple’s home. A new upbeat ending did not dissuade reviewers from speaking of the overall depressing qualities of the film. Audiences were not deterred, though, and even Wallis was astonished by the film’s box-office success.

Shirley Booth’s career on the big screen would not outlast the 1950s. Her most memorable work was probably in two other Daniel Mann-directed films, About Mrs. Leslie (1954), and Hot Spell (1958). Hard to cast in starring roles, she eventually attracted her largest audiences and pay cheques as Hazel on the small-screen (1961-66).

Like Booth, Anna Magnani (1909-1973) was making her American film debut in the role that won her a Best Actress Oscar. Internationally known since the success of her performance in her friend Rossellini’s Open City in 1945, Magnani was the very actress for whom Tennessee Williams had conceived the role of Serafina in The Rose Tattoo. Hampered by her inadequate English from creating the role on Broadway, she was persuaded nonetheless to undertake the film version. (Wallis considered Maureen Stapleton who did play the original Serafina too young and too American for the film). Williams volunteered to coach Magnani in English, and a special script was prepared written in Italian on one page with an English translation opposite it. Her resulting dynamic performance as the banana trucker’s widow who mourns her he-man’s death until she meets a second trucker with a rose tattoo like her husband’s was unlike anything ever previously seen in an American film. The awards were inevitable.

This time, Lancaster (replacing Eli Wallach from the Broadway cast for box-office appeal) fared less well with the critics. Fulfilling a contractual obligation with Paramount, he attempted an Italian accent which is at times almost hilariously inadequate. But at least his portrayal of the good-natured if dull-witted suitor contained a physical vitality which almost matched Magnani’s. A decade later, Lancaster chose to play a Frenchman in John Frankenheimer’s The Train without the slightest attempt at a French accent. The result was even more disastrous. One only wonders why he didn’t stick to roles as the anglophone American which he so unequivocally is and which he so strongly can portray!

Tennessee Williams purists may tend to deplore the changes which censorship pressures of the period imposed on the film’s script. As Maurice Yacowar points out in his Tennessee Williams and Film, “Where the play exalted passion, the film values marriage.” Yacowar complains that in the film everything is reduced, including the tonnage of the trucks, the lustfulness of the rampaging goat, the unseen mystery of the deceased husband (never seen in the stage version), and the Freudian symbolism of the bananas. At least the rampant symbolism of the ubiquitous roses, tattooed and otherwise, remains untampered with, representing desire more clearly than any conceivable “Streetcar”. And as if a husband named Rosario Delle Rose were not enough, Williams blessed the second trucker with the name of “Magiacavallo” or “Eat-A-Horse”. Attentive viewers may, by the way, glimpse both Williams and Wallis as extras in the casino scene.

Magnani’s post-Oscar career in American films parallels Shirley Booth’s. Equally difficult to cast–and far more difficult to direct!–Magnani made only a few more films before returning to the European career from which she had come.

As for director Daniel Mann, he would direct some more filmic adaptations of Broadway plays such as Teahouse of the August Moon (1956) and Five Finger Exercise (1962), and direct yet another actress to an Oscar (Elizabeth Taylor in Butterfield 8) before declining into a series of poorly chosen vehicles. His reputation appears to rest primarily on tonight’s two films which the Oscar nominators clearly admired. Sheba was nominated for three, but with Booth the only winner. Tattoo, on the other hand, was nominated in eight categories, including Best Supporting Actress (Marisa Pavan), score, editing, costumes, and Best Picture. In addition to Magnani, cameraman Howe and the art directors were actual winners. There is some irony in the art direction award, for this was a category for which the Sheba voters of 1952 could not even cough up a nomination for the same designers. Tonight’s viewers, with the opportunity to view these classic films back to back, may delight in an unusual shock of recognition. For in spite of some atmospheric location shooting for The Rose Tattoo next door to Tennessee William’s property in Key West, both films use some identical studio sets. Mann was nominated for neither film, but curiously enough, the winner of the Best Director award in the year of Tattoo was yet another Mann, Delbert, the director of Marty. Despite several coincidences in taste and style, and much public confusion in sorting out their respective careers, these two Manns are not related.

Notes by Cam Tolton

TORONTO FILM SOCIETY MEMBERS may be interested to know that our founders, Oscar and Dorothy Burritt, received mention in Canada; From Sea Unto Sea, published by The Loyalist Press Limited, 2233 Argentia Road, Suite 302, Mississauga, Ontario L5N 2X7. ($65.00 up to October 16, 1986; $85.00 thereafter)

Leave a Reply