The Kennel Murder Case (1933)

Toronto Film Society presented The Kennel Murder Case (1933) on Monday, September 26, 2016 in a double bill with The Last of Mrs. Cheyney as part of the Season 69 Monday Evening Film Buff Series, Programme 1.

Production Company: Warner Brothers. Director: Michael Curtiz. Screenplay: Robert N. Lee, Peter Milne, from the story “The Return of Philo Vance” by S.S. Van Dine. Adaptation: Robert Presnell. Dialogue Director: Arthur Greville Collins. Photography: William Rees. Art Direction: Jack Okey. Editor: Ed McLarnin. Gowns: Orry-Kelly. Supervisor: Robert Presnell.

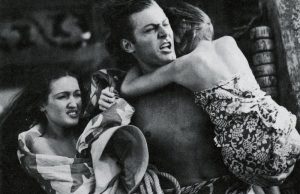

Cast: William Powell (Philo Vance), Mary Astor (Hilda Lake), Eugene Pallette (Sergeant Heath), Ralph Morgan (Raymond Wrede), Etienne Girardot (Doctor Doremus), Paul Cavanagh (Sir Bruce MacDonald), Helen Vinson (Doris Delefield), Arthur Hohl (Gamble), Henry O’Neill (Dubois), Frank Conroy (Brisbane Coe), Robert McWade (D.A. Markham), Jack LaRue (Eduardo Grassi), Don Brody (Quackenbush), Spencer Charters (Snitkin), Robert Barrat (Archer Coe).

Writer S.S. Van Dine spent two years writing his best novel, The Kennel Murder Case, which was published in 1933. He also joined Warner Bros. as a scriptwriter, and the studio hired William Powell to star as Vance in the film version of The Kennel Murder Case (1933), the best film adaptation of a Van Dine novel. Both the film and novel scenarios were situated at the Long Island Kennel Club.

Ron Backer writes the following about the film in his book Mystery Movie Series of 1930s Hollywood:

Michael Curtiz’s direction of The Kennel Murder Case is superb, as he uses a number of cinematic techniques to move the story forward. In order to maintain a variety of shot compositions so as never to allow the film to become static, there are camera shots from low-and high-angle perspectives, shots of characters’ reflections in mirrors, and shots of characters speaking with an extra, inanimate object in the frame. There are the passing camera shots of a train station’s clocks which establish one character’s alibi for another’s murder, which require the viewer to pay close attention. There are quick camera pivots within and between scenes as the camera moves from one party to the other, dissolves and wipes between scenes and even a split screen employed during a telephone conversation. There is a striking shot of a body through the bedroom door keyhole, with the camera somehow moving through the keyhole to focus in on the corpse. All of these cinematic tools transform a story which is essentially a talkfest into a story that is always moving and never boring.

But cinematic technique alone cannot make a great detective movie. In the end, a mystery needs a great plot and The Kennel Murder Case has it. The story is one of the most complex ever filmed and yet the viewer can easily understand the denouement, as Vance explains the crimes through the use of building models and a brilliant flashback sequence describing the murders. The flashback sequence is silent except for the narration of Vance and some important sounds such as falling bodies and gunshot. The camera seems to prowl through the house as the murders and other strange goings-on occur. Many other mystery films simply have the detective explain the solution to the murder to a group of suspects gathered at the end of the film, in a very boring manner. Curtiz demonstrates the better way to handle the denouement of a movie whodunit, using cinematic techniques rather than long speeches to explain the situation. The flashback sequence from The Kennel Murder Case is one of the highlights of the mystery movies of the 1930s.

Interestingly, the film has more suspects than the novel, as Sir Thomas McDonald does not appear in the book and Doris Delafield is only mentioned therein. Another difference is that the dog who heads into the mansion and then is severely injured was a Scottish terrier in the novel but a Doberman pinscher in the film.

The mystery in the book makes more sense than in the film, as Vance explains how he knew who the killer was by a convincing analysis of the clues. There is no guesswork on the part of the great detective in the novel, as there seems to be in the film. However, the movie is far more entertaining, as the audience does not have to be bored by Vance’s tedious monologues on Scottish terriers, Doberman pinschers and Chinese antiques. Also, the flashback sequence gives a visual explanation to the crimes that is hard to replicate in print.

Introduction by Caren Feldman

The Kennel Murder Case, the fifth film to be based on S.S. Van Dine’s Philo Vance novels, is one of the very best films of its genre and William Powell, flawlessly cast as Vance, was by far the most satisfactory of the ten players who took on the role between 1929 and 1947. Not only was Powell facially and physically ideal and at the right age to play the debonair Vance but, also, since he had specialized in villain roles in silents, he was able to suggest without overstressing it the very faint hint of cruelty that existed in the character as written by Van Dine. In the novels, Vance was always right, but somewhat longwinded and pompous, as he expounded his theories on the psychology of crime.

In the movies, the essence of the character remained, but Powell’s charm managed to translate the pomposity into a kind of amiable smugness. Robert McWade, a good character actor from Warner’s stock company, made an ideal District Attorney Markham—peppery, a bit quick to jump to conclusions, but basically as intelligent as a man in that position should be. Eugene Pallette as Sergeant Heath was the inevitable dumb assistant, used mainly for (mild) comedy relief, but with the saving grace (rare in such a stereotyped role) of being hard working and dedicated to his job.

The beauty of the film is that it succeeds despite the limitations of its breed, and without really departing from a formula which was then very popular. Van Dine’s novel is beautifully constructed and, unlike most movie adaptations, this one follows its parent novel to the letter.

Although the film is inevitably talkative, it manages to avoid the static, ponderous quality which had marred Powell’s earlier Vance films at Paramount, The Canary Murder Case and The Greene Murder Case (both directorially dull and overlong), and which would likewise mar many later Vance essays. From its impressive opening titles of a flashlight beam on a shuttered window, The Kennel Murder Case has real zip and pace. Potentially slow scenes are broken up via camera movement, interesting lighting, and a stress on low-angle compositions which seem to put the audience into an eavesdropping position. There are some unusually good miniatures of the adjoining houses, which figure so prominently in the action, and Curtiz frequently resorts to swish pans to keep the tempo lively. The foreground dialogue is suave, polished, and informative, as it should be in those mystery circles, while the background dialogue, all but thrown away, is both naturalistic and crackling.

The Detective In Film by William K. Everson

(Original Notes for Summer Series of August 25/26, 1975)

Leave a Reply