Seven Days to Noon (1950)

By Toronto Film Society on September 26, 2016

Toronto Film Society presented Seven Days to Noon (1950) on Sunday, September 25, 2016 in a double bill with The Spy in Black as part of the Season 69 Sunday Afternoon Film Buff Series, Programme 1.

Production Company: London Films. Produced, Directed, and Edited by John Boulting and Roy Boulting. Screenplay: Frank Harvey and Roy Boulting. Based on an original story by Paul Dehn and James Bernard. Photography: Gilbert Taylor. Music Composed by John Addison. Played by The London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Dr. Hubert Clifford. Made at London Film Studios Shepperton.

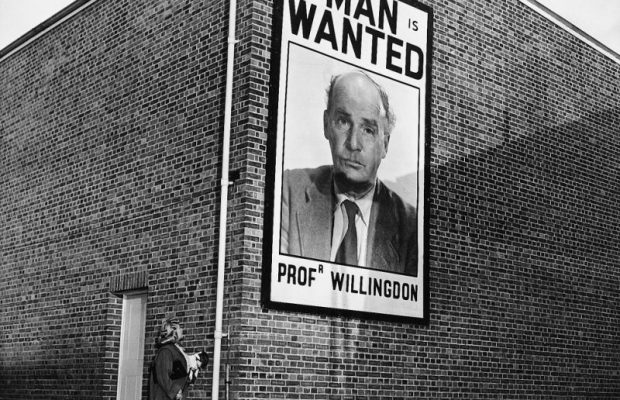

Cast: Barry Jones (Professor John Willingdon), Olive Sloane (Goldie Phillips), André Morell (Superintendent Folland), Sheila Manahan (Ann Willingdon), Hugh Cross (Stephen Lane), Joan Hickson (Mrs. Peckett), Ronald Adam (Prime Minister Arthur Lytton), Marie Ney (Mrs. Willingdon), Goldie Wyndham (Rev. Burgess).

Tonight’s second film duo are directors John Edward and Roy Alfred Clarence Boulting, identical twins born on December 21st, 1913 in Bray, Berkshire, England. Educated at Reading School, they showed an early interest in film by forming a school film society as well as acted as extras in Anthony Asquith’s 1931 film Tell England. In 1937 they created their own production company, Charter Film Productions, where they were able to produce many of their films.

The brothers worked together, alternating between the roles of producer and director, working on scripts whenever necessary along with making films separately from each other. This looks to be the only film they jointly directed. In 1947, prior to Seven Days to Noon the brothers made the classic Brighton Rock, starring Richard Attenborough, with John directing and Roy producing.

Each brother was married nine times between them. In 1966 Roy directed Hayley Mills in her first adult role in The Family Way, and although there was a 33-year difference in age, they married in 1971, producing a son, Crispian Mills, divorcing in 1978.

Coming into the world together, they died 16 years apart. John, at the age of 71 and Roy at the age of 88, both from cancer.

Introduction by Caren Feldman

Producer-directors John and Roy Boulting consolidated their reputations with this gripping, apocalyptic thriller, the relevance of which remains undiminished today. Shot in the summer of 1949 (just as the Soviet Union detonated its first nuclear bomb) and released in September 1950, Seven Days to Noon was praised by Time & Tide as “the most intelligent film so far to touch upon one of the problems confronting an atomic age,” while Picturegoer drew attention to its other great achievement, that it “brings London to the screen more realistically than has ever been done before.”

Utilising some 70 locations around the city, the film remains a vivid snapshot of postwar London and its populace, particularly in its astonishing scenes of mass evacuation. “This complete exodus of the world’s largest city is being carried out coolly, resolutely, and without panic,” observes a US radio correspondent, referencing the kind of community spirit recently called upon in the Blitz. And the Boultings’ scenes of a deserted city have an eerie potency faithfully reproduced in much later films like 28 Days Later (directed by Danny Boyle in 2002).

Ingeniously simple yet thought-provoking in its contemplation of scientific responsibility, the story was the work of critic Paul Dehn and composer James Bernard, who shared an Oscar for it. The film is also distinguished by Gilbert Taylor’s crystalline photography and expert performances from Oliver Sloane, Andre Morell (whose Superintendent Folland was revived for Roy Boulting’s 1951 solo film, High Treason), and, above all, Barry Jones as the anguished Professor Willingdon. Though the Boultings cover their backs by emphasising Willingdon’s derangement, he is nevertheless given the film’s most eloquent and moving speeches, when he observes that “All over the world, people are moving like sleepwalkers towards annihilation.”

Though set in the future–a Daily Express headline places the action in August, 1952–Seven Days to Noon, for all its overtones of Armageddon, is not a science-fiction film. It did, however, exercise a profound influence over several sci-fi/horror hybrids turned out by British filmmakers in the years to come. Its troop movements, church interiors, city-wide searches, and noirish mood of suppressed hysteria would be echoed, for example, in both The Quatermass Xperiment (directed by Val Guest, 1955) and The Children of the Damned (directed by Anton Leader, 1963). The former even incorporated the Boultings’ military dragnet footage into its climactic search for a mutating astronaut.

Notes by Peter Poles

You may also like...

-

News

Frances Blau

Toronto Film Society | February 27, 2024On Monday, February 26th, 2024, Toronto Film Society lost longtime friend, supporter, and board member Frances Blau. Known for her sense of humour, her love of film, her generosity,...

-

Special Events

The Ladykillers (1955) at the Paradise Theatre

Toronto Film Society | March 9, 2024Toronto Film Society presents Targets (1968) at the Paradise Theatre on Sunday, April 7, 2024 at 2:30 p.m. Ealing Studios arguably reached its peak with this wonderfully hilarious and...

Programming

Virtual Saturday Night at the Movies

Toronto Film Society | April 11, 2024Toronto Film Society is back in the theatre! However, we’re still pleased to continue to bring you films straight to your home! Beginning Season 73 until now we have...

4-

Toronto Film Society | March 9, 2024

Toronto Film Society | March 9, 2024

-

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

-

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Donate to Toronto Film Society – We’re now a Registered Charity!

-

Copyright © 2017 Toronto Film Society.

Leave a Reply