Success at Any Price (1934)

Toronto Film Society presented Success at Any Price (1934) on Sunday, September 23, 2018 in a double bill with Broadway Bad as part of the Season 71 Sunday Afternoon Special Screening #3.

Production Company: RKO Radio Pictures. Director: J. Walter Ruben. Producer: Merian C. Cooper. Screenplay: John Howard Lawson, Howard J. Green. Cinematography: Henry W. Gerrard. Film Editing: Jack Hively. Art Direction: Alfred Herman, Van Nest Polglase. Costume Design: Earl Luick. Music: Bernard Kaun. Release Date: March 16, 1934.

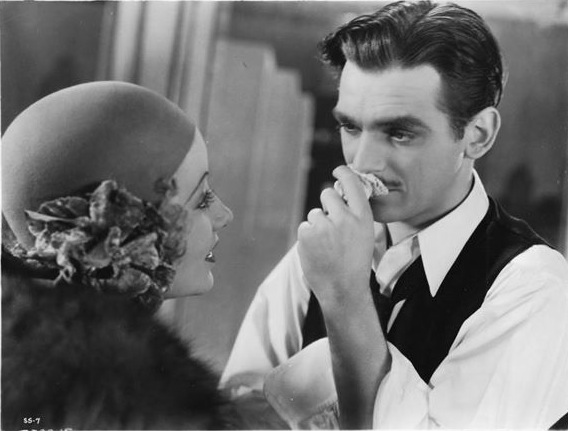

Cast: Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. (Joe Martin), Genevieve Tobin (Agnes Carter), Frank Morgan (Raymond Merritt), Colleen Moore (Sarah Griswold), Edward Everett Horton (Harry Fisher), Nydia Westman (Dinah McCabe), Henry Kolker (Mr. Hatfield), Allen Vincent (Geoffrey Halliburton).

So now that you know who Allen Vincent is—that miserable cad—you can look out for him in this next film. Here, at least, he finished his college education and works at a fairly good-salaried job when we first meet him.

I first saw this film several years ago at Toronto Film Society’s May film weekend and it stuck with me. Although it is a pre-Code, it was the subject matter that I thought unusual for the time, and it was interesting to note that the writer of the play and screenplay, John Howard Lawson, was head of the Hollywood division of the Communist Party for several years and one of the members of the Hollywood Ten during the McCarthy era. It’s definitely something to keep in mind as the story unfolds.

Colleen Moore, who was a huge star in the silent era, has a small role as the faithful love interest and secretary to Douglas Fairbanks Jr. with the unattractive name of Sarah Griswold which seems to go with the unflattering make-up and hairstyle they gave her. She made one more film, The Scarlet Letter, the same year and then retired from films completely. Moore was a shrewd investor and besides writing her autobiography, Silent Star in 1968, she also wrote two books on investing. One of her non-film legacies is the magnificent fairy castle dollhouse she had built between 1928 and 1935, which is housed at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago. It’s well worth the trip just to see it!

Genevieve Tobin was cast in the role of Agnes, the beautiful woman who uses her charm and looks to full advantage. But no matter, both Fairbanks and Frank Morgan, the head of the company, are way off in left field when it comes to understanding her. It’s interesting that regardless if we’re watching a film from 1934 or a modern TV show such as A Handmaid’s Tale, the basic storyline of power between the sexes hasn’t changed all that much.

I always find the ages of the actors interesting. For instance, Doug Fairbanks Jr. did a remarkable job in this role at the age of 25. Colleen Moore and Genevieve Tobin were both 34. We know that Agnes is supposed to be older and wiser than Joe, but I’m not certain whether Sarah was supposed to be older rather than closer to his age. To me, Colleen looked older than 34 possibly due to her plainness, but I also think her unadorned looks are supposed to be juxtaposed against Agnes’s glamor. But, hey, maybe Fairbanks was playing someone older than a 25-year-old.

The ending of this film is not what you might anticipate, and the 180-degree shift in Fairbank’s character’s attitude is quite sudden. It also feels like a throw-away, censored ending. The simplest reason may be that not only the title but possibly the ending of Lawson’s play, Success Story, was changed for the filmed version, as Hollywood was wont to do.

Although there are some films from this period that don’t have a musical score, I think you will find it quite noticeable that Success at Any Price had none notwithstanding the music played in the opening and closing credits.

I hope you enjoy this film with its rather mature, sometimes flirty dialogue which occasionally refers to topics taboo in films made after 1934.

Introduction by Caren Feldman

Success at Any Price: A

This picture, for the most part, is a faithful transcription of the stage play, “Success Story”, which set forth the tragedy of a man who sacrificed everything for cash and power. Most of it is hard-hitting drama in which Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., as the success-ridden principal character, does the best work of his career. It concludes with a forced happy ending that is as affrontingly inappropriate as a Bronx cheer in church. The film follows the play script faithfully to the point where Joe Martin (Mr. Fairbanks) reaches the pinnacle of success and shoots himself. Thereafter, take it from the optimistic movies, he recovers to live happy ever after with his long-faithful and long-neglected girlfriend (Colleen Moore). There ought to be a law.

A fine case has something into which it can get its teeth. The story is ruthless and shrill, and Mr. Fairbanks’ development, or deterioration, from a cocksure, sullen boy into an overstrained magnate is worth going miles to see. Genevieve Tobin plays a nitwit woman with a perfect balance that keeps her from being either hardboiled or sentimental, and Ralph (sic) Morgan is a convincingly sleek executive. This is a distinctly worth-while picture, despite its sloppy conclusion. High Spots: The discharged Merritt (Mr. Morgan) and the discarded Sarah (Miss Moore) trying to hide their hurts by laughing. Aggie (Miss Tobin) coming home tight at 5 a.m.

The New Movie Magazine: First Nights on Broadway by Frederic F. van de Water, Jul-Dec 1934

While all films, to a degree, reflect the times in which they are made, certain key films, especially when the dominant contributing artist is the writer rather than the director, become especially interesting as mirrors of their era. Sometimes, indeed, that importance and interest transcends their value as film. Tonight’s two films [Bill Everson also screened To The Victor (1948)] are linked, in that both are somewhat sour views of the times in which they were made—the Depression and the post-World War Two period. The earlier Depression films (I Am A Fugitive From a Chain Gang) tended to be screams of outrage and protest; by 1934, however, it had become clear that the corner around which prosperity lurked was still many blocks away. Films shifted gears somewhat and romanticized the Depression, kidded it, or as here, sullenly lambasted what is always ambiguously referred to as “the system”. It’s a strange film of the period, yet lacking the humor that Warners would have injected, via Frank McHugh or Allen Jenkins, as an antidote. It was one of the earlier screenplays written by John Howard Lawson and, since it is based on his own quite well received play, can be considered very much a personal point of view.

Lawson, of course, as one of the “Unfriendly Ten”, achieved some notoriety during the McCarthy era as an alleged Communist propagandist, and his career was aborted thereby. While one always tends to feel sympathy for the artist at the mercy of the political witch-hunter, the suspicions concerning Lawson are not entirely unfounded. His screen-writing career was not prolific, and was quite liberally dotted with war stories like Blockade, Counter Attack, Sahara, and Action in the North Atlantic, where the odd political lines could be slipped in casually. Apart from its underlying theme of revolution against the ruling classes almost for its own sake, there is no real Communist thrust to Success at Any Price, but as in Lester Cole’s screenplay for The House of Seven Gables, while it may not be pro-Communist it is most certainly anti-American, at times! Success at Any Price, in any case, is a strong, powerful little picture with mature situations and dialogue and a commendably unsympathetic performance from Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.—quite a departure for him at a time when he was coming into his own as a very likeable young leading man. Genevieve Tobin is, as always, elegant and sophisticated; a perfectly understandable reason for anyone to leave his wife or fiancée. In the latter role, Colleen Moore has practically a carbon copy of her role in the previous year’s The Power and the Glory, but she isn’t kindly treated by the camera, or indeed by the writing of the role itself. And Frank Morgan, though in a (for him, at that time) stereotyped role, reminds us again what a good dramatic actor he was before MGM turned him into a comic buffoon.

The New School Film Series by William K. Everson, March 17, 1978

Then I accepted the only offer on my immediate horizon and started homeward again. This job was several notches below what I’d hoped for. To be called Success at Any Price, the film was hardly more than a fancy Hollywood potboiler. It would be saved by the immensely popular Colleen Moore. …Neither Colleen nor I can any longer recall a single thing about the plot of Success at Any Price, but I do very clearly remember the many good wishes offered me for a long-contemplated campaign to find the backing needed to form my own producing company.

The Salad Days by Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. (1988)

The moral equivalence between crime boss and capitalist executive is schematic in Success at Any Price (1934), directed by J. Walter Ruben from the play by John Howard Lawson. The narrative follows a heartless moneygrubber from 1927 to 1934; the Jazz Age to the Great Depression. Go-getter Joe Martin (Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.) works for an advertising company whose main client is “Glamour Cream”, an expendable consumer product of the 1920s rendered extravagant in the 1930s. The communist screenwriter Lawson laces the play with a venomous hatred for his antihero and the system he prospers under. Compared to Joe Martin, even Rico Bandello enjoys a warm personal life. The film opens with a Jazz Age prelude, a headline from 1927: Joe has just buried his gangster brother before setting out on a parallel career track in business. He is a dynamic workaholic, but a pathological one, betraying mentor, girlfriend, and business partners. In the last unpersuasive seconds of the film, the likable Fairbanks reveals the kind heart under his sinister skin, but Joe Martin has been a witting tool of capitalism too long to pull off a deathbed conversion.

Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema 1930-1934by Thomas Doherty (1999)

There was more than a hint (of social revolution) in Success at Any Price (1934), based on the play “Success Story” by John Howard Lawson (later blacklisted as one of the Hollywood Ten). It presented a man’s phenomenal rise in business as a consequence of his stunted moral and emotional nature. It was, in a way, a transparent, leftist diatribe. Yet it crystallized the era’s antibusiness sentiment and was precisely the sort of movie that could not be made once the Code was enforced. The Code arrived just three-and-a-half months after the release of the picture.

Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., in one of those young tough-guy roles he excelled at, played Joe Martin, who, on the day of his gangster brother’s funeral, decides to go straight and make his fortune within the system. His girlfriend (Colleen Moore) gets him an entry-level job in an advertising company, where she works as a secretary. When Joe, a lout with a chip on his shoulder the size of a piano, finally gets a chance to make good, his talent is recognized, and he begins his climb.

Joe is driven. He has nothing but his work, his anger, and his hunger. He meets his boss’s mistress (Genevieve Tobin) and decides he wants her—just like Scarface wanted his Boss’s mistress—as a symbol of his arrival. “If I had a million dollars, I’d buy you,” he says. She understands. She is all about money, too, and sold her soul long ago. “I know how you feel,” she tells him. “Anything you can’t get makes you sick and sour.” To make his million, he buys stock and sells short; rides employees to the breaking point; and ultimately pulls a power play, squeezing out the boss who gave him a chance in the first place. “We cleaned up on Wall Street with tricks that would make a gunman blush,” he says. “There are no ethics in this town. It’s kill or be killed. Get what you can.” It’s not until his expensive, worthless wife (Tobin) betrays him that he sees his harsh life as having no meaning, no connection, no value, and no hope. It’s for these kinds of moments that characters in movies always keep a revolver in their desk. Success at Any Price ends with a tableau of male fragility; Fairbanks is resting his head on Moore’s lap as they wait for the ambulance to arrive.

In their depiction of the business world, pre-Code movies were turning their gaze on the arena in which most men spent their working lives. “Something is missing here,” these films were saying. “Something about this is antithetical to life.”

Dangerous Men by Mick LaSalle (2002)

Notes compiled by Caren Feldman

Leave a Reply