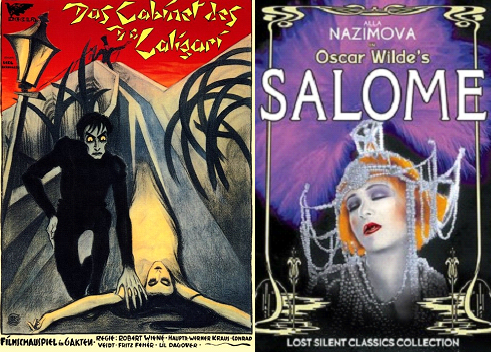

The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari (1919) and Salome (1922) [abridged]

Toronto Film Society presented The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari (1919) on Saturday, October 28, 2023 as part of the Season 76 Virtual Film Buffs Screening Series, Programme 2.

Toronto Film Society presented The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari (1919) on Monday, February 19, 1968 as part of the Season 20 Monday Evening Silent Film Series, Programme 4.

Programme No. 4

Monday February 19, 1968

Salome (abridged) (U.S.A. 1922) (approx 30 min)

The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari (Germany 1919) (1 hour 9 min)

Since our print of Salome is only a condensed version of the original (it’s all that’s available–outside of the Gallery of Modern Art in New York which, unlike the Museum of Modern Art, doesn’t circulate its films) and is therefore not much longer than a short, we are presenting it first. Otherwise we should have preferred to show these two films in their chronological order . . . which is the order in which they will be discussed in these notes.

-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-

We have placed these two films on the same program tonight because of the element which the two have in common: both have highly stylized settings (one might justifiably refer to them as “décors”) inspired by certain art movements still current at the time. Caligari, made in Germany in 1919, derived from Expressionism, a German branch of the Cubism which was the rage and scandal of the years just prior to the outbreak of World War I (though Salome was inspired by the so-called illustrations (“decorations” would be a better word; illustrations they are not) by Aubrey Beardsley for the first published edition (1894) of the play by Oscar Wilde on which the film is based. In this year of grace 1968 there is no need to tell you (as was an artist associated with that fin de siècle rococo movement known as “Art Nouveau” which flourished in the 1890s and early 1900s and was well on its way out by the time Salmoe was filmed in 1922, . . . but which has made an astonishing comeback in the 1960s, answering some current hunger for a combined kookiness, extravagance and nostalgia. (Perhaps, since Art Nouveau is the older of the two movements, we are showing our two films in their proper chronological sequence after all).

The later film may or may not have been inspired by the earlier one, but the use of fantastically stylized sets, though refreshingly new to the screen, derived from examples in the contemporary avant-garde theatre . . itself in turn probably influenced by the Diaghileff Russian Ballet which had had such an impact in Europe in the years between 190 and the outbreak of the War (and indeed afterwards). Diaghileff’s practice of commissioning décor and costume designs from avant-garde painters had an influence on stage design in all branches of theatre, and was bound to affect the cinema sooner or later, directly or indirectly. The makers of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari were not likely thinking of the Russian Ballet but of some of the experimental drama productions that were being done in certain Berline theatres at that time; the makers of Salome on the other hand undoubtedly were thinking of the ballet. But moviegoers of the time these two films were disconcertingly novel, and therein lies the legend of their reputation.

Having stated what these two films have in common, setting them apart from the more ordinary film (whether great like The Birth of a Nation or trivial like The Americano) it remains to be pointed out that the two films are as opposite as can be. German Expressionism was an attempt to “express” the inner feelings of a subject, with an earnestness bordering on hysteria. “An atmosphere of catastrophe in the social sphere, the division of the go in the private sphere, brooding revolt against the false, narrow morality and an ecstatic, almost religious individualism: these are the essential marks of German Expressionism” (Peter Thoene, Modern German Art, 1938). Outwardly a horror-thriller, like the Frankenstein or Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde films, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is a parable of tyranny and of individual responsibility. Art Nouveau, on the other hand, was basically a purey sensuous form of applied art. Oscar Wilde’s play, though outwardly a repulsive story of sexual perversion, is in reality only a colorful fabrication with no intent of reality, for the sake of its own gorgeous display–a product of and for the “hedonism that characterized the revolt of the avant-garde in the 1890s against Victorianism. Its appeal is purely sensual with no message to offer than its bizarre beauty (“art for art’s sake”) and a heady intoxication of the senses. It is pure decoration; and Aubrey Beardsley’s drawings have little or nothing to do with the text but are purely decorative end in themselves. (We can’t speak with authority on the film version which as yet we haven’t seen).

(It is not our aim to offer here a comprehensive study of Art Nouveau, Aubrey Beardsley and German Expressionism; we’d like to but we haven’t the qualifications. But if you are anxious to do plenty of homework before viewing these two films you might find it worth your while to read up0 on these subjects in whatever reference books you can find. You might also find it helpful to re-read Oscar Wilde’s play).

* * *

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

(Das Cabinet des Cr Caligari)

Production company: Decla-Bioscop

Producer: Rudolph Meinert

Director: Robert Wiene

Scenario: Hans Janowitz and Carl Mayer

Photography: Willy Hameister

Sets: Hermann Warm, Walter Röhrig and Walter Reimann

Released in North America by Goldwyn Pictures Corp. Apr 29, 1921

Original length: 6 reels

(Either they were very short reels, or else there’s something missing from current prints. The available 8mm print, based no doubt on the Goldwyn release, differs in a few slight details from the 16mm print which we are renting from the CFI, which was obtained from England; but substantially they are the same, and both are much shorter–less than 70 minutes even at silent speed–than a normal six-reel film).

CAST:

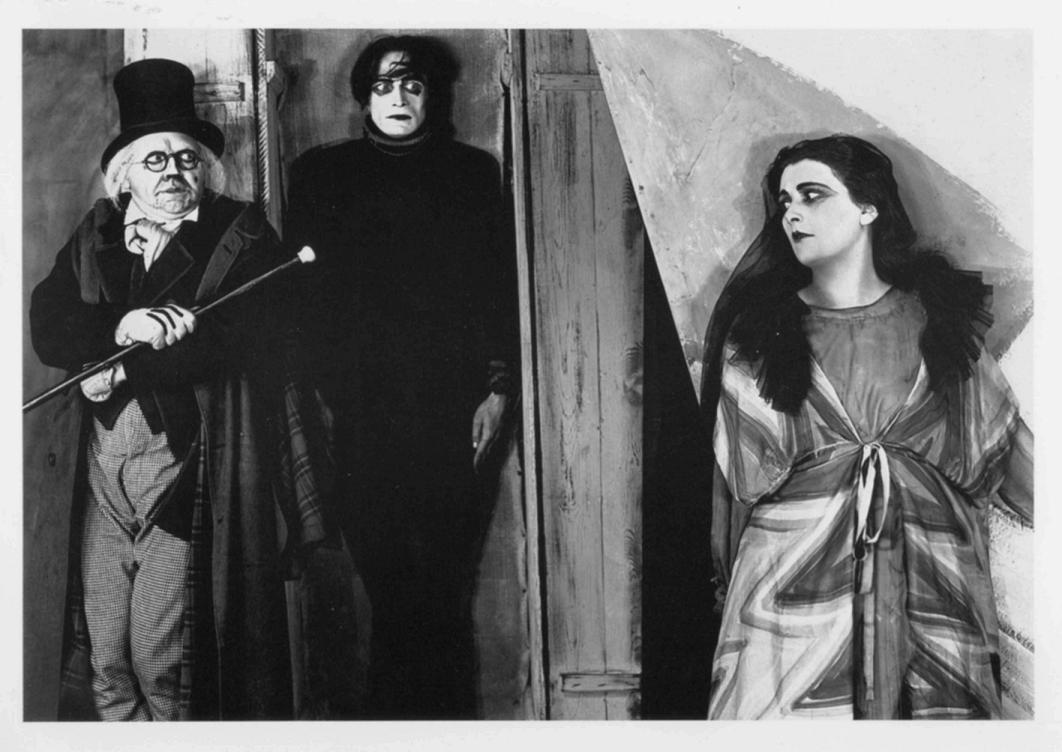

Dr. Caligari…………………Werner Krauss

Cessare…………………….Conrad Veidt

Jane Olsen…………………Lil Dagover

Francis……………………..Friedrich Feher

Alan…………………………Hans von Twardovski

Dr. Olsen……………………Rudolf Lettinger

Criminal…………………….Rudolf Klein-Rogge

One evening in October 1913 this young poet was strolling through a fair at Hamburg, trying to find a girl whose beauty and manner had attracted him. The tents of the fair covered the Reeperbahn, known to every sailor as one of the world’s chief pleasure spots. Nearby, on the Holstenwall, Leder’s gigantic Bismarck monument stood ssentinel over the ships in the harbor. In search of the girl, Janowitz followed the fragile trail of a laugh which he thought hers into a dim park bordering the Hostenwall. The laugh, which apparently served to lure a young man, vanished somewhere in the shrubbery. When, a short time later, the young man departed, another shadow, hidden until then in the bushes, suddenly emerged and moved along–as if on the scent of that laugh. Passing this uncanny shadow, Janowitz caught a glimpse of him: he looked like an average bourgeois. Darkness reabsorbed the man, and made further pursuit impossible. The following day big headlines in the local press announced: “Horrible sex crime on the Holstenwall! Young Gertrude…murdered”. An obsure feeling that Gertrude might have been the girl of the fair impelled Janowitz to attend the victim’s funerla. During the ceremony he suddenly had the sensation of discovering the murderer, who had not yet been captured. The man he suspected seemed to recognize him, too. It was the bourgeois–the shadow in the bushes.

The foregoing, though it may sound like something inspired by Blow-Up, was in fact the germ of the story that eventually emerged as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. The “young poet” was Hans Janowitz, a visitor from Prague–“that city where reality fuses with dreams, and dreams turn into visions of horror” (according to Seigfried Kracauer, from whose book “From Caligari to Hitler” the above paragraph was taken). At that time Czechoslovakia was still part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the World War that broke out the following year, Janowitz served as an officer in the infantry. By the war’s end he was a confirmed pacifist with a violent hatred for the authoritarian powers that had sent millions of people to their deaths. He settled in Berlin, where he made the acquaintance of one Carl Mayer, an Austrian who had similar embittered views resulting from his wartime experiences. Mayer had apparently been given a hard time by the military psychiatrist to whom he had been sent for mental examination during the war. Janowitz was a writer, Mayer had a theatrical background, but the two young men were caught up in the currently rising enthusiasm for the cinema as a serious art form with unlimited possibilities.

One night, on a visit to a Berlin fairground, they attended a sideshow in which they watched a man do feats of strength while in an apparent stupor, as if hypnotized, all the while uttering statements that sounded to the fascinated spectators like delphic prophecies. This at once set their creative juices flowing, and that very night the two friends worked out a Hoffmannesque story that incorporated elements of Janowitz’s prewar Hamburg adventure, his postwar hatred of authoritarianism, and Mayer’s hatred of his wartime psychiatrist. They worked on the manuscript for six weeks and then submitted it to the Decla-Bioscop film company in Berlin.

Their story (as you’ve probably heard even if you’ve never seen this film before) involved a sideshow operator named Dr. Caligari (the authors found the name in a book of Stendahl’s letters and appropriated it) who keeps a somnambulist (Cesare) under his hypnotic spell and sends him off to commit murders on Caligari’s behalf. To the authors, this symbolized the German military authorities conscripting the ordinary German citizen and sending him out to kill or be killed. The story (as Janowitz and Mayer wrote it) ended with the forceful overthrow of this authority.

(Kracauer’s whole book is a thesis that this film was a foreshadowing of Hitler; but of course its symbolism is applicable to any form of authority that uses its guiltless but sheeplike citizens as a weapon of offense. You can find your own examples, even at the present day).

The general manager of Decla-Bioscop (a company which later merged with Ufa) was Erich Pommer. This unsolicited manuscript from two unknown writers evidently caught his fancy, and he accepted it. Originally Fritz Lang was assigned to direct it, but pressure of other duties compelled him to be replaced by Robert Wiene. According to Kracauer, it was Wiene who had the bright idea of adding a prologue and epilogue so that the main story became an “as told to” flashback–a device as old as literary history. Much to the annoyance of Janowitz and Mayer, however, Wiene in the epilogue also gave the film a twist ending which completely negated their anti-tyranny theme. Whether Wiene did this on purpose, to tone down these revolutionary sentiments, or whether he merely took the story at its face value and introduced the new ending as a brilliant surprise gimmick (which it is) is not known.

Just whose idea it was that the settings for Caligari be “expressionistic” rather than realistic is still a matter of dispute. Janowitz had originally requested that the sets be designed by the Prague-born painter and illustrator, Alfred Kubin, “who, a forerunner of the surrealists, made eerie phantoms invade harmless scenery and visions of torture emerge from the subconscious”. Erich Pommer reports that he rejected this as being too costly and impractical, but as an alternative conceived the idea of doing them in the Expressionist style which would make a virtue of necessity: money and materials were scarce in Germany in 1919, and settings made of painted canvas would not only be cheap but could be turned into a daring artistic advantage. Robert Wiene, however, claims that this was his idea. But according to still another claim, it was the Director of Production, Rudolph Meinert, and not Pommer, who simply turned the assignment over to the designer Hermann Warm. Warm called in two friends, Walter Röhrig and Walter Reimann, both of whom were employed by the studio as painters, and the three of them studied the script together. According to Warm, it was Reimann who proposed that the sets be done in the Expressionist manner. Since all three were Expressionists in their own paintings, this idea appealed to them and they began at once to make sketches. The next day they showed them to Wiene who accepted them at once. Meinert asked for a day to think it over, then said “Go ahead and make your sets as mad as possible!”

The distorted, angular sets, deliberately artificial with obvious painted shadows, have always been interpreted as a clever reflection of the madness of the narrator, a satisfactory explanation for those many literal-minded persons who like to have a logical explanation for fantasy–like “it was all a dream”. But the fact remains that even the framing story has the same fantasy sets. The Expressionism was applied to the whole film not just to the inner story; just as was done later in such German pictures as The Golem (1920), Genuine (1920), Crime and Punishment (1923), Waxworks (1924) and others.

(Incidently, Caligari was not the first film in which obviously painted sets were used deliberately. We recall the American film Prunella (1919) with Marguerite Clarke, directed by Maurice Tourneur, with stylized sets by Ben Carré that imitated artificial stage sets, even to a painted moon).

One wonders, however, why only two of the actors, Werner Krauss and Conrad Veidt, adapted themselves to the Expressionism of the sets. The rest gave naturalistic performances (within the convention of the somewhat florid screen acting of the period, especially in Germany). Why didn’t the director have all the actors give stylized performances?–or were Krauss and Veidt acting on their own initiative?

For all its audacity in its use of far-out sets, Wiene’s film was strangely primitive in many other respects, and for this it has been severely criticized by later (not contemporary) critics. It is as if the technical advances of Griffith had never existed (and indeed it is possible that in 1919 The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance–both made during the war years–had not yet been seen in Germany). As is the old Méliès films, the camera takes up its stolid position and grinds away till the end of the scene, the actors entering and exiting as if on a proscenium stage. There is little imaginative use of either camera or cutting–and theoretically therefore this film isn’t cinematic and shouldn’t work; but it does–largely of course because its strong assets outweigh its defects. A few years later its Expressionism would have been achieved as much by camera effects as by sets. But in 191 these weren’t necessary; the Warm-Röhrig-Reismann sets and the Janowitz-Mayer macabre melodrama with its symbolical overtones made the film a dazzler, and no one then was concerned with what it should have been.

After a big publicity build-up The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was released in February 1920 in Berlin, and critics all praised it as the screen’s first work of art. Samuel Goldwyn bought the American rights and the New York premiere took place in April 1921. It ishardly surprising that in America (as in Germany too, for that matter) the general public failed to respond to this off-beat film–though its failure here was partly due to the still lingering anti-German sentiments; in fact the filmwas actually banned in some quarters for this very reason. But on critics and intellectuals it had a great impact, and was widely discussed, and brought a new respect and prestige to the screen. We don’t know that Nazimova’s decision to film Salome with sets inspired by Beardsley was influenced by the example of Caligari, but in a view of the fact that Salome was made in 1922, the year after Caligari was first seen in North America, it is a not unreasonable assumption.

We conclude as we began, with a quotation from Kracauer:

..While the Germans were too close to Caligari to appraise its symptomatic value, the French realized that this film was more than just an exceptional film. They coined the term “Caligarisme” and applied it to a postwar world seemingly all upside down; which, at any rate, proves that they sensed the fim’s bearing on the structure of society. The New York premère of Caligari, in April 1921, firmly established its world fame. But apart from giving rise to stray imitations and serving as a yardstick for artistic endeavors, this “most widely discussed film of the time” never seriously influenced the course of the American or French cinema. It stood out lonely like a monolith.

* * *

(Some FOOTNOTES: Werner Krauss, who also appeared in Waxworks, remained in Germany throughout his career; but Conrad Veidt moved to Hollywood in the latter part of the twenties and became a very popular star. He was active in American and British films until his death in 1943. His role in Caligari (he was 26 at the time) gives little inkling of the magnetic personality he displayed in his later films. Lil Dagover is said to be still active in German films. Carl Mayer, who had never do any writing before he collaborated on the script for Caligari, went on to write such screen plays as The Last Laugh, Tartuffe, and Sunrise. He died in 1944. Erich Pommer became head of Ufa (Germany’s biggest film company) and produced such films as Dr. Mabuse, Variety, The Last Laugh, Metropolis, The Blue Angel and Congress Dances. During a brief sojourn in Hollywood in the mid-1920s he produced some good films for Paramount including Hotel Imperial. In the thirties he was in England where among other things he produced and directed Charles Laughton’s The Beachcomber (1938) and produced Laughton’s The Sidewalks of London (1939). After the war he returned to Germany where he still lives.

Salome

From the play by Oscar Wilde

Produced by Alla Nazimova

Directed by Charles Bryant

Scenario by Alla Nazimova (under the penname “Peter M. Winters”)

Photography by Charles Van Enger

Design and Costumes by Natacha Rambova

Copyright by Nazimova Productions, Inc., Dec 15, 1922

Released by Allied Producers and Distributors Corporation

Original length: 6 reels.

The present print is about half this length. It is not an excerpt but an abridgement. We don’t know its history).

CAST:

Salome……………………….Alla Nazimova

Herodias……………………..Rose Dione

Herod…………………………Mitchell Lewis

Jokanaan…………………….Nigel de Brulier

Young Syrian………………..Earl Schenek

A Page……………………….Arthur Jasmina

Naaman, the Executioner….Frederick Peters

Tigellinus…………………….Luis Dumar

A few years after the disastrous box-office failure of Salome, Adela Rogers St. Johns (in an interview for Photoplay Magazine) asked Nazimova why she had made it. Nazimova explained that she had become so fed up with all the trashy films she had been making that she wanted to take the taste out of her mouth by doing something completely artistic. It proved an expensive mouthwash. She had financed the film with her own money, and it cost her her life’s savings.

Alla Nazimova was born in Yalta, Crimea, on June 4, 1879. She went to school in Switzerland, returned to Odessa and studied violin, gave it up at 17 to become an actress, and went to Moscow where she studied under Stanislavsky and eventually became a member of his famous Moscow Art Theatre. In 1904 she joined a company that toured Europe and the following year visited New York. In spite of the barrier of a foreign language, the critics were enthusiastic about her performances, and the interest of Broadway producers was aroused; and eventually the Shuberts offered her a contract, provided that she could learn English. On November 13, 1906, Nazimova made her English-speaking debut in “Hedda Gabler”. Its success was followed by a succession of plays by Ibsen, Chekhov and others. (My father saw her on the stage during this period, and he reports that her accent was so thick that you couldn’t make out a word she said . . yet so great was her acting that you understood her perfectly). In 1916 she was touring the Keith vaudeville circuit in a one-act play “War Brides” (with Richard Barthelmess as her leading man) when Lewis J. Selznick offered her $30,000 to make a screen version of it. (This was in the days when Hollywood was busily signing up all the important stage stars it could get). The film (in which Barthelmess made his screen debut) proved a great box-office success, and the Metro company signed her to a long-term contract; and with her exotic beauty she became one of their most popular stars.

Her films for Metro included Revelation, Eye for Eye (1918); Out of the Fog, The Red Lantern, The Brat (1919); The Heart of a Child, Madame Peacock and Billions (1920). Some of these films were quite poor (we are told), and some of the roles, in her determination to prove her versatility, were unsuited to her; at any rate, her box-office appeal was fading by this time. Her last film for Metro (or one of the last, at any rate) was Camille, directed (like most of her films) by her husband, Charles Bryant, (not to be confused with another contemporary director, Charles Brabin, who was Theda Bara’s husband). Her art director by this time was Natacha Rambova; and the up-and-coming young actor, Rudolph Valentino, fresh from his triumph in The Four Horsemen, was cast as Armand. (With fatal results for him, for he fell in love with the beautiful Miss Rambova and eventually married her; her well-meaning attempt to manage his career nearly wrecked it).

Natacha (sometimes spelled Natasha) Rambova was born Winifred Shaunnessey in Salt Lake City in 1897. Her mother later married Richard Hudnut (the cosmetics king), which Winifred in the wealthy leisure class, resulting in much travel throughout Europe, where she became interested in painting and sculpture; and she went to school in England. She became interested in ballet, and in New York she studied under Theodore Kosloff, a former member of the Russian Imperial Ballet (and a member of Diaghileff’s first ballet company in 1909), and became a member of his little ballet group which toured the country in the Keith vaudeville circuit. For this purpose she adopted the professional name of Natacha Rambova. (It was the practice of English and American dancers at this time and for many years later to take Russian names when they joined a ballet company; it seemed to give the public more confidence in them). When the Kosloff Group arrived in Hollywood, Kosloff met Cecil DeMille, who put him into many of his films (and he remained in Los Angeles where he operated a dance studio until his death in 1956). Natacha, having by this time decided that she was more interested in designing than in dancing, looked around the Hollywood studios for a possible outlet for her talents. Nazimova met her and was impressed.

To what extent Rambova exerted an influence on Nazimova, or merely happened along when Nazimova was headed in the same direction, we don’t’ pretend to know, not being possessed of enough information. In view of her later artistic ambitions for Valentino, it is quite conceivable that it was she who instigated Nazimova’s desire to wash the taste out of her mouth; at the very least she obviously encouraged her. When the actress’s contract with Metro expired, soon after Camille (released Sept 1921), Nazimova formed her own company, financed by herself. (This was the practice in those days; the present custom of getting bankers and other financiers to angel your films didn’t come till later). Her first production was A Doll’s House (released by United Artists in February 1922), and when the public failed to respond, she decided to go for broke with the bizarre and outré Salmone, which must have been very satisfying to make, but which she must have known would never go over with the paying public.

With all her money gone, she returned to work as an actress for other companies, making such films as Madonna of the Streets (1924) and My Son (1925) for First National, and The Redeeming Sin (1925) for Vitagraphy, and also resumed her stage career, appearing with the Civic Repertory Theatre and the Theatre Guild in productions of Ibsen, O’Neill, Chekhov, et al. Not until 1940 did she return to films, by which time she was in her sixties. She played character roles in such films as Escape (1940), Blood and Sand (1941; the Tyrone Power remake), The Bridge of San Luis Rey and Since You Went Away (1944), until her death froma heart attack in 1945 at the age of 66.

Natacha Rambova divorced Valentino in 1926, a few months before his death. She never remarried but lived at home with her widowed mother. She became interested in Egyptology, and helped produce a number of books on Egyptian archeology, mythology and history for the Bollingen series. She died less than two years ago, June 5, 1966, in Pasadena, California, at the age of 69.

That Salome didn’t fare well with the public at large is not surprising. The more perceptive critics appreciated it, but it never became the legend that Caligari did. You can read many a book on film history without finding a single reference to it. (Probably because it had absolutely no influence on any other film; historians can never forgive this). What references there are frequently contradict one another, leaving the reader curious and puzzled. Was Salome pretentious artiness, or was it really years ahead of its time? Or years behind its time, founded as it was on the already old-fashioned Art Nouveau? This indeed may have been the barrier. (In 1938 we find the French writers Bardèche and Brasillach, in their “History of Motion Pictures”, dismissing this part of Nazimova’s career with the statement that under Bryant’s direction she “made some mediocre films–a Salome after Wilde with settings that looked like the cheapest kind of art pictures sold by the big stores, and an agitated and feverish Doll’s House“). Today, however, when we once more respond sympathetically to Art Nouveau and especially to Beardsley, it is significant that there has also been a renewed interest in the Nazimova-Rambova Salome.

Will the film be exciting to us, or just ridiculous? Is it great? or poor? or is it just a noble effort that doesn’t quite come off, to be admired more for its brave aim than its accomplishment? Was Natacha Rambova an unappreciated genius or a horrible perpetrator of bad taste? Stills from Salome (and from her Camille too) have always been tantalizing. She was obviously an artist of very unusual and origianl ideas, but presumably they are so extreme that inevitably one either loves them or hates them according to one’s own aesthetic chemistry. (“What is truth?”)

But be it beautiful or just silly, artistic or just arty, the film has one other claim to our consideration quite apart from the question of its own merits: it seems to be the only Nazimova film available, our only chance to see this once more celebrated screen star in her prime.

I have called Nazimova an actress, but the word is badly chossen. Pauline Frederick, in the same age, was an actress–and what strong sure acting hers was, with what a passionate acceptance of screen dimensions! Litlle Mae Marsh, at the time of The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance, had in her the bones of great acting. But Nazimova was a dancer. Her face was always a fine mask, beautiful but impenetrable, changing slightly with her changing films, but never allowed to become mobile. It was her body that was her language, and a body trained and persuaded to the limits of the camera. Her gestures had been shaped in the lfat, not in the round, and always with a sense of pattern; she knew every poses and poise of expression in two dimensions–how to use limbs and throat and tilted head to strengthen and complete the design on the screen. Thinking of Nazmova now, back through the years, I can always see her poissed and balanced, on the tip of movement like some Hermes in bas-relief, her bare face curiously masked, every line of the body composed for the cameras in a fine consciousness of its own validity and grace.

(C.A. Lejeune, Cinema, 1931)

* * *

(FOOTNOTE): We have been told that one of the costumes worn in Salome was used again many years later in Kenneth Anger’s film Pleasure Dome).

* * *

A NOTE ON THE MUSIC FOR Caligari

Because our accompanying musical score was made over a year ago for the TFS North York season in 1966, we are in the unusual position of being able to tell you ahead of time what the music is going to be. (If you’re interested). The musical counterpart of the Expressionist movement in Germany at that period was the nerve-stretched music of Arnold Schoenberg and his two pupils, Alban Berg and Anton Webern, so not surprisingly the score makes considerable use of compositions of Schoenberg and Webern (nothing by Berg, as it happens). We thought of limiting ourselves to music that was in existence in 1919, but this proved too confining–though actually all our Webern pieces are pre-1919 and all but one of the Schoenberg,–and the exception was his “Begleitungsmusik” (1930), his film score for an imaginary film, of which we made extensive use (so that it has at last become a score for a real film). We also used Debussy (“Jeux” and the flute solo “Syrinx”) and a Charles Ives piece; but the rest was post-1919 (much of it however by composers who were already established by then: Stravinsky, Prokofiev and Respighi), including some of the unsung by valuable composers who provide music for the various “mood music” recordings issued exclusively for the use of broadcasting and film studios. The barrel-organ was actually recorded in Hamburg, which is rather appropriate.

(We won’t know what music we’ll be using for Salome until we’ve had a chance to see the film. The score used by the live orchestras for the original presentation of the film was based on Richard Strauss’s opera, and the print prepared for the Gallery of Modern Art has a sound track with Strauss’s music played on a pipe organ. We doubt if we can follow these examples; orchestras and organs can use special arrangements of the music, but for us, restricted as we are to recordings, operas usually have too much singing to be practical. We’ll just have to wait till the film arrives and see what it’s like).

Notes by Fraser Macdonald

-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-

NEXT SHOW: Monday March 25: The White Hell of Pitz Palu (Germany 1929), starring Leni Riefenstahl; directed by Arnold Fanck and G.W. Pabst.

Leave a Reply