Whoopee! (1930)

Toronto Film Society presented Whoopee! (1930) on Sunday, June 23, 2019 in a double bill with Wake Up and Dream as part of the Season 71 Sunday Afternoon Special Screening #12.

Production Company: The Samuel Goldwyn Company. Director: Thornton Freeland. Producers: Samuel Goldwyn, Florenz Ziegfeld. Screenplay: William M. Conselman, based on the story “The Wreck” by Robert Hobart Davis, Edith J. Rath, William Anthony McGuire, and adapted play “The Nervous Wreck” by Owen Davis. Cinematography: Lee Garmes, Ray Rennahan, Gregg Toland. Film Editing: Stuart Heisler. Art Director: Richard Day. Choreography: Busby Berkeley. Release Date: October 5, 1930.

Cast: Eddie Cantor (Henry Williams); Ethel Shutta (Mary Custer); Paul Gregory (Wanenis); Eleanor Hunt (Sally Morgan); Jack Rutherford (Sheriff Bob Wells); Walter Law (Jud Morgan); Spencer Charters (Jerome Underwood); Albert Hackett (Chester Underwood); Chief Caupolican (Black Eagle); Lou-Scha-Enya (Matafay); Dean Jagger (Deputy); Marian Marsh (Harriett Underwood); Virginia Bruce, Claire Dodd, Paulette Goddard, Betty Grable, Ann Sothern (Goldwyn Girls).

Today’s film, Whoopee! is Florenz Ziegfeld’s only credited film venture as co-producer, along beside Sam Goldwyn. It appears Goldwyn didn’t let Ziegfeld lend any of his skills in the making of this film; it was more in name only. “Whoopee” (minus the exclamation mark) was Ziegfeld’s very successful stage play about a nebbishy hypochondriac preserved on film. And although Eddie Cantor made two silent films and two shorts prior to Whoopee!, this is the movie that made him a film sensation.

Whoopee! is stocked full of many firsts and the unusual. One of the earliest talkies filmed in two-strip Technicolor it also boasts Busby Berkeley’s film debut. No one had seen anything like Berkeley’s choreographed sequences before. It’s interesting to read how he came up with his camera technique to film all these lovely, barely clad beauties. And speaking of Hollywood beauties, these lovely maids were given the name Goldwyn Girls. Here we’ll see, at the very beginning of their careers, a 14-year-old Betty Grable—leading many of the lineups, so watch for her face—Virginia Bruce, Claire Dodd—who nowadays is a much lesser known name—Paulette Goddard, Jean Howard—who settled down to married life with famous talent agent Charles Feldman and produced a coffee table book in 1989, Jean Howard’s Hollywood—and Ann Sothern. Photography was done by three cinematographer greats, Lee Garmes—think of Shanghai Express—assisted by Ray Rennahan, cinematographer on the 1935 Becky Sharp, the first film to be made in three-strip Technicolor, and Gregg Toland of Citizen Kane fame.

In the 1930s, blackface was a common form of entertainment that dates back as early as 1441. Blackface became popular in the United States with the British play “The Padlock” which premiered in New York City on May 29, 1769. From these roots, in around 1810, blackface comedy arose. White comic actor Thomas D. Rice truly popularized blackface when he introduced the song “Jump Jim Crow” accompanied by a dance in his stage act of 1828. Rice travelled the US performing under the stage name “Daddy Jim Crow”, becoming a star by 1832. The name “Jim Crow” later became attached to statutes that codified the reinstitution of segregation and discrimination after the Civil War in the Southern States. Once blackface became popular, it was used in minstrel shows, then waned and was used by vaudevillians. So, Eddie Cantor, who never directly comes out and says he is Jewish although there are quite a few Jewish gags in the film, is also a minority, and as a vaudevillian, does have a blackface sequence in Whoopee! And just to be inclusive, Native Indians are also featured—but only one of these races or religions is acceptable for intermarriage with Gentiles.

A big question here is, at least to me: Does Eddie Cantor have sex-appeal? It’s hard to say and even harder to know if he’s supposed to. He is the love-interest for his nurse, Mary Custer, played by stage actress Ethel Shutta who reprised her role for the film. And then there’s the very odd scene between Cantor and Spencer Charters where they are looking down each other’s pants while rolling around on the floor together, supposedly comparing scars.

Interestingly, Cantor’s stage and film persona were somewhat licentious, but in reality he was a happily married man with five daughters, living, unlike many of his contemporaries, a quiet life which did not include nightclubs, drinking, other women or consorting with mobsters.

The humour is slapstick, the jokes are what you imagine you might hear in the Catskills back in the day, there’s singing and dancing and a degree of wackiness. It’s beautiful to look at even when the Goldwyn Girls are not in sight, and so I hope you enjoy this comedy from another era.

Sources: The Eddie Cantor Story: A Jewish Life in Performance and Politics by David Weinstein (2017), Wikipedia

Introduction by Caren Feldman

The Play:

William Anthony McGuire’s libretto for the new show, a musical version of Owen Davis’s play The Nervous Wreck, cast Cantor as Henry Williams, a helpless hypochondriac sent out West for his health. Cantor knew that he could play the role, after his recent illness. Ziegfeld though so, too, calling it a case of “one hypochondriac playing another.” The show would be called Whoopee. Whoopee started as a story called “The Wreck,” written by Edith R. Rath in collaboration with Robert Davis, that began serializing in the Argosy-All Story Magazine of December, 1921. Producers Albert Lewis and Max Gordon had the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Owen Davis adapt it for the stage under the title of The Nervous Wreck in 1923, and a 1926 film version had (the original) Harrison Ford, Phyllis Haver, and Chester Conklin in the leads.

Cantor was not yet involved in the show’s preparations. He spent six weeks, that summer, in the famed Battle Creek Sanitarium, recuperating from the remnants of his pleurisy, doing what amounted to role research for Whoopee, and working on his autobiography, My Life Is in Your Hands, with the writer David Freedman. Ziegfeld was now busy casting Whoopee in New York. He had already signed Ethel Shutta to play Eddie’s nurse/love interest, Mary Custer; Frances Upton for the ingenue role of Sally Morgan; Ruby Keeler for the role of Harriet Underwood; and Ruth Etting for the singer Lesley Daw. William Anthony McGuire, Walter Donaldson, and Gus Kahn, in the meantime, had gone to a retreat in the Adirondacks to do further work on the score and libretto. Donaldson and Kahn then went to Chicago to complete the songs in company with Cantor.

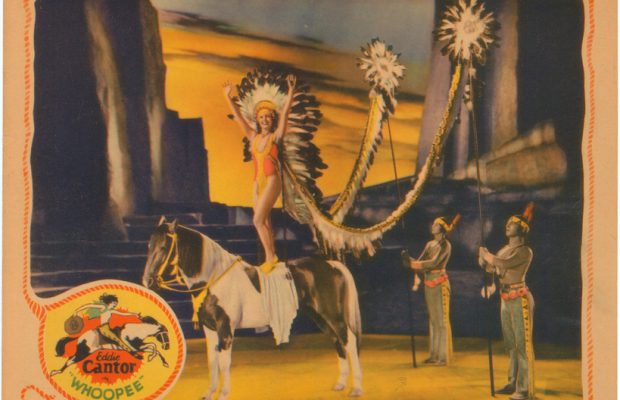

Rehearsals started early in October. Whoopee was more than simply a vehicle for Eddie Cantor’s talents. Based on a hit comedy, it boasted a fine score and was mounted with all the care and lavishness for which Ziegfeld was famous. Flo, in fact, spent hours going through hundreds of hats before he found the ten-gallon Stetsons that Ziegfeld Girls would wear. The sets were by Joseph Urban, whose great scenic work had transformed the Follies from a well-produced topical revue and girl show into a work of art in 1915. Seymour Felix did the dances, and George Olsen’s band augmented the pit orchestra. Whoopee epitomized what 1920s audiences demanded from musical comedy. From the semi-nude showgirls parading as Indian maidens to the resplendent “Halloween Whoopee Ball,” the show was breathtaking, tuneful, and, above all, funny, appeasing all the muses in a complete entertainment. Ziegfeld thought of all finales, then a most important part of any Broadway show, in terms of color. Whoopee had a pink and silver finale that even impressed the color-blind Cantor.

The show was still in need of work when it opened at the Nixon Theatre in Pittsburgh on Election Night. Added to the usual headaches was the sudden departure of Ruby Keeler, who left Pittsburgh to join Jolson, her new husband, in Los Angeles. Mary Jane Kittel, an attractive young blonde tapper, was put into Ruby’s part, and Whoopee moved on to Newark, Washington, and finally, New York, opening at the New Amsterdam on Tuesday night, December 4, 1928. That the show was a resounding hit is quite beyond dispute. Cantor, Ethel Shutta (a forgotten but truly delightful performer who returned to Broadway in the musical Follies in the 1970s), and Ruth Etting (whose three spoken lines drove The Gimp into ecstasies) came in for the critical raves, with Frances Upton and Paul Gregory almost wasted as romantic leads. Ziegfeld’s breathtaking production, Urban’s sets, and the score—“Makin’ Whoopee,” “Love Me or Leave Me,” “I’m Bringing a Red, Red Rose,” “Stetson”—all came together to create what would be the Roaring Twenties’ last great show. The Broadway critics offered little except praise, but were not oblivious to the production’s faults. “It is not, of course, a perfect show,” reported Richard Lockridge. “Even with such cutting as has no doubt already been done, it stretches out lengthily through the evening. Now and then its plot, based on Owen Davis’ The Nervous Wreck, seems a little flat and we are left with the sad spectacle of Indians calling, solemnly and with much hitting of wrong notes, for justice. Now and then, the funny lines are not so very funny; a little dismally fell the discovery that the tenor was not part-Indian, after all. With malice, one searches for defects and brings up these. And Whoopee rolls over them.”

Whoopee closed on Broadway on November 23, 1929, four weeks and two days after “Black Thursday.”

The Film:

Samuel Goldwyn had already bought the movie rights from Ziegfeld, and plans now called for Cantor to tour in the show through March 15. Goldwyn, and not Ziegfeld, was now firmly in command. Cantor, fearful and resentful, began bombarding Goldwyn with demands in much the same way he had pestered J.J. Shubert, nine years earlier. BELIEVE IT BEST FOR SUCCESS OF PICTURE THAT I HAVE A HAND IN WRITING OF SCRIPT, he wired from Chicago, where Whoopee had begun a six-week run. Goldwyn calmly sent his writers, who had yet to put a word on paper, out to visit Cantor. They listened to his numerous suggestions and answered every question with the key word “motivation.” Every song or dance or sequence, as they saw it—anticipating Rodgers and Hammerstein by thirteen years—had to grow organically from the show’s plot and characters. That, of course, was not how Whoopee was created. Cantor also insisted that Goldwyn hire Busby Berkeley, choreographer for Earl Carroll’s Vanities, as the picture’s dance director. Checking up on Berkeley, Goldwyn learned he had a drinking problem. Nonetheless, he soon gave in to Cantor’s wishes. Berkeley was hired, beginning a career that would revolutionize the American film musical.

Berkeley, William Conselman, the chief scenarist for Goldwyn, and Thornton Freeland, who would direct the film Whoopee!, met with Cantor when the show played Cleveland, the last stop on its tour. Cantor and Berkeley went to Child’s after the final performance, and “Bus” sketched designs for the dance numbers on the backs of menus. The next day, he entrained for Hollywood with Conselman and Freeland. Cantor returned to New York and spent the next two weeks in conference with Ziegfeld. Eddie had little time to spend with his family on this trip to Hollywood. The film version of Whoopee was scheduled to shoot and wrap in thirty-six days. Indoor sequences were shot first, in Hollywood, with the outdoor scenes filmed later, in Palm Springs. The principal Broadway cast of Whoopee was used for the movie version, with one notable exception: Frances Upton, who failed to pass Goldwyn’s screen test. Eleanor Hunt was jumped up from the chorus to play Sally Morgan. The cast rose at 4:30 on the desert to start work at six. “This was June,” remembered Cantor, “and by eleven a.m. you were falling down with the heat.” Director Freeland had a crew “planting” poppies in the desert at five o’clock in the morning. As Eddie came onto the set, Eleanor came rushing up with a hundred poppies she had picked for him, her “leading man.” Freeland almost died.

Whoopee! is not so much a movie as a filmed stage show. Unlike similar such efforts, there is not even the pretense of an “adaptation” to the screen, only a judicious pruning of some dialogue and most of the Kahn-Donaldson stage score. There is the distinct feeling of being on a sound stage—Whoopee! almost seems to be on tape rather than film—and the primitive, two-color technicolor is so effective that one can practically see blue, a color that this process was unable to produce. Busby Berkeley more than vindicated Cantor’s choice of him as dance director. While his production numbers are not the isolated worlds within themselves that they would be in his coming days at Warners, Berkeley’s imaginative use of the sound camera included overheads (first seen in The Cocoanuts) and—a Berkeley original—the spotlighting of each individual beauty in his chorus (including Betty Grable) in a fast-paced series of charming head shots. Cantor’s performance is delightful, his timing perfect, and his rendition of a new song, “My Baby Just Cares for Me,” provides some of the most inspiring, spontaneous moments in the history of film. Rivaling him is Ethel Shutta, whose comedy and singing of the rousing “Stetson” number make one wonder why she made no other pictures. Shutta would return to Broadway forty years later, introducing the song “Broadway Baby” in the Stephen Sondheim musical Follies.

Goldwyn, notwithstanding, was aghast at the dailies. The scenes and jokes that seemed so funny when he saw the show onstage now seemed corny and flat. His star remonstrated. “How can it be funny here with three of us sitting a room? In a theatre, it plays to an audience of hundreds, and they laugh.” Cantor’s answer pacified Sam Goldwyn, but it only hints at the main problem. Like the material of stand-up comics, which is crafted toward small rooms, large rooms, television, or convention centers, the jokes and bits that made up 1920s musicals were conceived in terms of a particular size audience. Whoopee!, as Cantor predicted, would prove funny and play well before large audiences in motion picture theatres. The same holds true for the film now. Audiences at the Museum of Modern Art howled at its comedy—both topical and otherwise—and cheered at the film’s ending in the 1970s. On small-screen television, played before an audience of ten or fewer people, the jokes and gags seem leaden and banal. (One becomes aware of pauses after lines and bits, as actors wait for laughs unlikely to come from audiences of two or three people watching TV in a living room.) All of Eddie Cantor’s movies suffer on television; Whoopee! simply dies.

The picture was completed by late-June, only seven days behind schedule, and previewed in San Diego in July. Ziegfeld, virtually ignored during the filming, accompanied Cantor to the theatre, saying Hollywood was not the place for Eddie and urging him to return to Broadway. “Wait till we see the picture, Flo. If I squeeze your hand, we’ll talk about another show.” There was no squeeze; the film was good. Cantor’s personal contract with Goldwyn, calling for one more picture if the first one proved successful, was replaced on July 19 by a new, three-film contract. Eddie had now cast his bread on the Pacific Ocean.

Banjo Eyes: Eddie Cantor and the Birth of Modern Stardom by Herbert G. Goldman (1997)

Notes compiled by Caren Feldman

(to read more notes on Whoopee! click here)

Leave a Reply