Act of Violence (1949)

Toronto Film Society presented Act of Violence (1949) on Sunday, April 15, 2018 in a double bill with The Third Man as part of the Season 70 Sunday Afternoon Film Buffs Series, Programme 7.

Toronto Film Society presented Act of Violence (1948) on Monday, September 26, 1988 in a double bill with The Big Clock as part of the Season 41 Monday Evening Film Buffs Series “D”, Programme 1.

Production Company: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Producer: William H. Wright. Director: Fred Zinnemann. Screenplay: Robert L. Richards from a story by Collier Young. Cinematography: Robert Surtees. Music: Bronislau Kaper. Release Date: February, 1949.

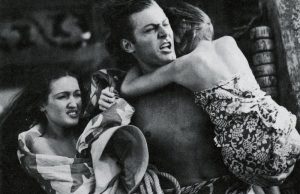

Cast: Van Heflin (Frank R. Enley), Robert Ryan (Joe Parkson), Janet Leigh (Edith Enley), Mary Astor (Pat), Phyllis Thaxter (Ann Sturges), Barry Kroeger (Johnny), Harry Antrim (Fred Finney), Connie Gilchrist (Martha Finney), Will Wright (Pop).

Act of Violence is an impressive noir that uncovers the darkness and violence hidden behind the curtains of brightly lit streets of American suburbia. It explores, through the characteristic noir themes of revenge and guilt, the lasting effects of wartime experience on people.

Protagonist Frank Enley harbours a dark secret about his war service that the arrival of a wounded comrade in his idyllic suburban home threatens to expose. Joe Parkson, the damaged man seen limping into Frank’s small Californian town in the film’s credit sequence, is a symbol of the psychic wounds of war. Similarly, the darkness that comes to envelope the home Frank shares with his wife, Edith, is an image of the persisting shadow cast by the war over postwar American life. And this story takes place over two days and nights.

In its visual style, Act of Violence efficiently evokes the contradictions of postwar America. Pride in war service is symbolized by a military parade of veterans in progress on the day Joe arrives in town, but its positivity is undercut by the sight of him limping counter to the rhythm of their healthy march. A housing project opening, which salutes Frank’s dynamism, represents postwar promise which counters the darkness that becomes visible in Frank’s house as the story progresses. You will notice the lighting change depending on the action of the characters.

The film comes from a first story by Collier Young, the former husband of Ida Lupino and at the time of this film, married to Joan Fontaine, with a tough, tight script written by Robert Richards, done economically and effectively while doing its damaging bit to present a real Americana, crowded with weak people and desperate compromises.

The film is typical of director Zinnemann’s detached, dispassionate tone but that it is still very subjective in such scenes, when drawing the audience inside the mind of Frank. It is an unusual picture of the slow stain of war.

Sources: Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style by Alain Silver and Elizabeth Ward (1988); Encyclopedia of Film Noir by Geoff Mayer and Brian McDonnell (2007); “Have You Seen…?”: A Personal Introduction to 1,000 Films by David Thomson (2008)

Introduction by Caren Feldman

Our first film of Series “D”: Films of 1948 is graced by the presence of a couple of top-flight actors who never received as many choice roles as they deserved, but always turned in solid, well-crafted performances—Van Heflin and Robert Ryan. Both are cast in roles which typified, to some extent, their careers: Heflin the devious and high-strung loser; Ryan the charismatic, forceful man with a very definite plan of action—in this case, to avenge himself on Heflin for betraying his men while in a POW camp.

This was one of the first films directed by Fred Zinnemann, who went on to helm some of the top films of the 1950s. Zinnemann, already displaying signs of his great talent, created an atmosphere of harsh realism and kept things moving at a brisk pace.

Two of the female parts are played by actresses with contrasting degrees of experience: Mary Astor, in films since the 1920s and Janet Leigh, in one of her earliest outings. (Incidentally, in her recent autobiography, Ms. Leigh mentioned that she had taken the spelling of her stage name from Vivien Leigh, about which the British actress was not amused.) Mary Astor, who, for most of her career, played major supporting roles (with The Maltese Falcon a notable exception), was cast as an ageing, sleazy, world-weary prostitute (although never identified as such, due to censorship rules). Although her part was small, she prepared for it with gusto. Ms. Astor wore a dress bought in a bargain basement (complete with cigarette burns and coffee stains); bracelets that rattled and jangled; chipped nail polish; and an excess of makeup.

For fun, Mary, so attired, dropped in on director Mervyn Leroy, who was shooting Little Women on an adjoining soundstage. Leroy, startled at her appearance, exclaimed, “You look like a two-bit tart!” Astor was very pleased.

Notes by John D. Thompson

Leave a Reply to Anonymous Cancel reply