The Private Affairs of Bel Ami (1947)

Toronto Film Society presented The Private Affairs of Bel Ami (1947) on Monday, July 16, 2018 in a double bill with Mad Love as part of the Season 71 Summer Series, Programme 2.

Production Company: United Artists. Producer: David L. Loew. Director: Albert Lewin. Script: Albert Lewin, based on the 1885 novel by Guy de Maupassant, “Bel Ami”. Cinematography: Russell Metty. Film Editor: Albrecht Joseph. Music: Darius Milhaud. Production Design: Gordon Wiles. Art Design: Frank Sylos. Set Decoration: Edward Boyle. Release Date: April 25, 1947.

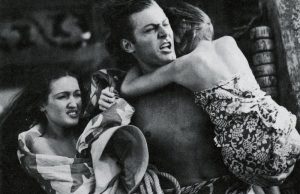

Cast: George Sanders (Georges Duroy), Angela Lansbury (Clotilde de Marelle), Ann Dvorak (Claire Madeleine Forestier), John Carradine (Charles Forestier), Susan Douglas (Suzanne Walter), Hugo Haas (Monsieur Walter), Warren William (Laroche-Mathieu), Frances Dee (Marie de Varenne), Albert Bassermann (Jacques Rival), Marie Wilson (Rachel Michot), Katherine Emery (Madame Walter), Richard Fraser (Philippe de Cantel), John Good (Paul de Cazolles).

There’s an interesting little anecdote how advance publicity was concocted for The Private Affairs of Bel Ami. The director, Albert Lewin, dreamed up an art competition by inviting world-famous artists to submit and display their paintings of the temptation of Saint Anthony, with the winner’s painting to be displayed in the final scene of the film in Technicolor, no less. The final decision would be made by someone from the public, being a contest winner themselves. Max Ernst’s painting won over the other artists, which included Salvador Dali’s version of the Saint’s temptations.

And back on the note of censorship, after Ernst’s picture was chosen, his and the other artists’ paintings were exhibited in New York City. When the exhibition came to Boston, Mayor James M. Curley banned it, arguing that the paintings were offensive on a religious-moral basis. After Loew and Lewin filed a $200,000 suit against the mayor, the local Stuart galleries exhibited the artworks.

Of course, Joseph Breen and the Production Code had much to object to in this film, beginning with the various elements of the film’s preliminary treatment. These included the characterization of Marie Wilson’s “Rachel” as a prostitute; a scene of “Rachel” and “Georges” alone together in her room; a scene in which Georges and Katherine Emery’s character “Madame Walter” swear their love inside a church; and the suggestion that Ann Dvorak’s character “Madeleine” was illegitimate.

In early February 1946, Breen asked Lewin to rewrite the script to eliminate the “flavor of too much emphasis on disrespect for marriage and infidelity.” Then, in April 1946, Breen insisted that the relationship between Georges and Angela Lansbury’s character Clotilde be strictly platonic.

According to the Variety review, Lewin was forced to remove any indication that Georges consorted with prostitutes, as depicted in the novel, and was made to add an ending to uphold the Production Code’s edict that crime must not pay in films.

Despite all the censorship, Bel Ami still proves to be a beautiful film worth viewing.

Sourced from TCM

Introduction by Caren Feldman

Plot: Georges is a womanizer out to increase his social status. He attends a party with his friend Charles and Charles’ wife, Madeleine. There he meets Madeleine’s friend Clotilde, who becomes his lover. But when Charles dies, Georges marries Madeleine for her money. He then frames Madeleine for adultery and marries Suzanne Walter. But his social climbing catches up with him in ways that will not be revealed here.

Production: The film was the swan song of the actor Warren Williams, who was in poor health throughout the filming. Actress Susan Douglas, whose first role this was, had to sign a seven-year contract and was told that, otherwise, she would not be allowed to make any more films. Max Ernst’s painting of “The Temptation of Saint Anthony”, which is one of the focal points of the story, is shown in full colour in an otherwise black-and-white film—a device that Lewin, who was a friend of Ernst, had used in his earlier The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945).

Reception: Variety, acknowledging the censorship problems posed by the source novel, called the film “a scrubbed-face version of the complete scoundrel” depicted by Maupassant, in order to comply with the edicts of the Production Code. The cast, however, is “exceptionally strong” and Lewin’s direction is “skilled”. Sanders plays his role “with the correct hammy touch” and utters de Maupassant’s epigrams effectively, while the five women seduced by him “all show well”. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times, however, found the film “tiresome”, with the actresses performing “as posily and pompously as they are compelled to talk”.

Albert Lewin (1894-1968): After an early academic career and military service during World War I, he went to Hollywood to work for Samuel Goldwyn and became a screenwriter at MGM in 1924. There he became producer Irving Thalberg’s personal assistant and closest associate, and produced several of MGM’s most important films of the 1930s. After Thalberg’s death, he worked for Paramount on such films as Zaza (1939) and So Ends Our Night (1941). The half-dozen films that he scripted and directed himself were often based on literary sources, such as The Moon and Sixpence (1942) and The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945). He retired from film making after suffering a heart attack in the late 1950s.

George Sanders (1906-1972): Born in Russia of British parents who moved to England during his childhood, where he began to act on stage and in films in the 1930s. His upper-class English accent led to his being often cast as a sophisticated, but also often villainous, character in many of his British and later American films. Sanders’ roles as “The Saint” and later “The Falcon”, in B-movie series, alternated with work for Alfred Hitchcock in Rebecca and Foreign Correspondent and various Hollywood titles, such as Confessions of a Nazi Spy; The Moon and Sixpence; The Black Swan; The Lodger; Ivanhoe; and probably his finest role, in All About Eve (1950), for which he won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor. Later roles, and films, were often less distinguished and he began to suffer various health problems and depression and resorted to heavy drinking, all of which culminated in his suicide in a hotel in Spain in April of 1972. His wives included two of the Gabor acting sisters, Zsa Zsa and Magda.

Angela Lansbury (born 1925): Born in England to an Irish mother and an English father who was an active politician in the Communist party, she became obsessed with theatre and film when she was young. Her father died when she was nine. She moved to New York with her mother (a film and theatre actress) in 1940 to study acting, then joined her mother in Hollywood. There she met the playwright and scriptwriter John Van Druten, who recommended her for a role in the film of the play Gaslight, directed by George Cukor, for which she received a nomination for Best Supporting Actress. This was followed by a small role in National Velvet (1944) and then a major role in The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945), for which she again received a nomination for Best Supporting Actress and a Golden Globe Award. But this led only to a series of mediocre films for MGM, who treated her simply as a B-list actress, to her increasing dissatisfaction. When her MGM contract ended, she worked in some better received films; most notably, The Manchurian Candidate, in 1962, but moved more frequently to the theatre and achieved stardom for the musical Mame in 1966. She achieved her greatest fame in television, however, for a long-running drama series, Murder, She Wrote, from 1984 to 1996. She won numerous nominations and awards for both film and television, and received an Honorary Oscar Award in 2013. She was married twice and had two children with her second husband. She has been a generous supporter of several philanthropic charities.

John Carradine (1906-1988): A prolific actor who appeared in over 200 films and is probably best known as a member of John Ford’s stock company; he made 11 films for Ford, including The Prisoner of Shark Island; The Grapes of Wrath; Stagecoach; and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. He also appeared in dozens of low-budget horror films from 1940 onwards.

Notes by Graham Petrie

Leave a Reply