Escape (1940)

Toronto Film Society presented Escape (1940) on Monday, January 14, 2019 in a double bill with Five Came Back as part of the Season 71 Monday Evening Film Buff Series, Programme 4.

Production Company: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Producers: Mervyn LeRoy, Lawrence Weingarten. Director: Mervyn LeRoy. Screenplay: Arch Oboler, Marguerite Roberts, based on the novel by Grace Zaring Stone (under the pen name Ethel Vance). Cinematography: Robert H. Planck. Music: Franz Waxman. Release Date: November 1, 1940.

Cast: Norma Shearer (Countess von Treck), Robert Taylor (Mark Preysing), Conrad Veidt (General Kurt von Kolb), Alla Nazimova (Emmy Ritter), Felix Bressart (Fritz Keller), Albert Bassermann (Dr. Arthur Henning), Philip Dorn (Dr. Ditten), Edgar Barrier (Commissioner), Bonita Granville (Ursula), Elsa Bassermann (Mrs. Henning), Blanche Yurka (Nurse), Lisa Golm (Anna).

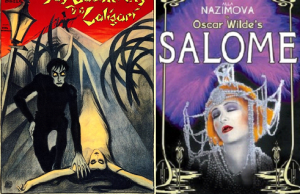

Alla Nazimova was a world-famous actress, and a superstar in films from the mid-teens until the mid 1920s. She was born on June 4th, 1879 in Yalta, Crimea, in the Russian Empire to Jewish parents, Sonya Horowitz and Yakov Leventon. They named her Miriam Edez Adelaida, calling her Adel until her mother decided that Alla was prettier. Sonya adored this second daughter and third child partially out of guilt for having tried to miscarry when she was pregnant. Her parents had a tumultuous relationship which affected the household, and one night Sonya stole away, taking three-year-old Alla with her to live with her new lover in another town. Yakov sabotaged this relationship, divorced his wife and brought Alla back home. Sadly, Yakov was also an abusive parent who seemed to relish exercising his wrath against his youngest child. So, Alla had to learn to live in a household without a loving mother, an abusive parent, and a step-mother and siblings who were less than supportive.

Nazimova’s life changed when she discovered drama at her boarding school at the age of 15.

Her brother Volodya was the oldest sibling and became her guardian when her father was sent to a sanatorium after suffering a third stroke. However, she rebelled against this timid brother, especially once their father died as a feeble old man and who could never beat his youngest daughter again. Her other sibling was an older sister, Nina, who was envious of her youngest sister’s relationship with their mother when they were very young and seemed to carry on this feeling of jealousy throughout their adolescence. Nina was treated kindly by their father, which didn’t help the sisters’ relationship. However, as Nazimova’s star rose, she was there for her sister, sending for her once she was established in the US, allowing Nina and her children to live with her. Nina’s son, Nazimova’s nephew, incidentally, grew up to become Val Lewton.

But by the time tonight’s film, Escape, was in pre-production, Nazimova was no longer a household name. She hadn’t made a film since 1925 and when she was even considered for a role, Maria Ouspenskaya usually won out over her. But both screenplay writer Arch Oboler and original director George Cukor wanted Nazimova to play the actress Emmy Ritter, and in early March she went to LA to make a test, directed by Cukor. Cukor eventually called Nazimova to say that producer Lawrence Weingarten decided to replace him, first with Alfred Hitchcock who turned the offer down, worried that MGM would want too much control over him, then with director Mervyn LeRoy, who accepted the job. Cukor also warned her that another writer, Marguerite Roberts, had been hired to develop a subsidiary character as a leading role for Norma Shearer, a role which was not in the original novel by Grace Zaring Stone, and who wrote the book under the pseudonym Ethel Vance. A second screen test was called for, this time directed by LeRoy, with Oboler giving her advice to underplay. With her hair dyed black, the makeup man confided that Judith Anderson, who was also in the running for the role, “tested too sinister…and looked too, what you think? Jewish! That tickles me pink, considering she hasn’t a drop of it.” Nazimova won the role while Anderson, who also hadn’t been in a film since 1933’s Blood Money, went on to become the immortal Mrs. Danvers in what also was Hitchcock’s American debut as director, Rebecca.

There is a scene where Nazimova’s character is put into a coffin, and while the lid was being nailed shut, she found herself reflecting on the fact of how fortunate she was to be alive after having beaten the cancer she had been ill with only three years earlier. She felt grateful for her new chance in life.

With regards to Norma Shearer, she was a gracious person, especially noted considering her role in Escape was thin and poorly developed, and she suggested on one occasion in particular to build up Nazimova’s part. However, Blanche Yurka, who had lobbied for Nazimova’s role and settled for the much smaller part of a nurse in the concentration camp, was what Nazimova described as a “sour puss”. Apparently, there was a scene that was later cut in which actress Emmy Ritter plays the dying Camille for a group of fellow prisoners because it was ruined by Yurka muffing the best take. I think that would certainly have been fun considering that it was still probably a well-known fact that she had made the famous silent version with Rudolph Valentino in 1921.

Depending on which biography you read on Norma Shearer, Laurence J. Quirk’s take on the actress’s role is different than Gavin Lambert’s. Quirk interviewed a number of Hollywood people who felt that Norma’s energies were zapped due to a lack of a full personal life during the time of making Escape. Irving Thalberg had died in September 1936 and she didn’t marry again until 1942. Although Norma was financially secure, a millionaires many times over as well as holding a large amount of MGM stock in her portfolio, she still worried about her reputation as an actress. Robert Taylor, in this first of two films he made with her—the second was Her Cardboard Lover in 1942—claimed, “She was a perfectionist and while that can be fine, and often helps other performers reach the same standard, I always felt she was nit-picking and fussy about lighting and angles and all the rest of it because she was compensating for something—some lack in her life. I don’t think she cared much for the picture, wanted to get it over with, but oddly enough she was, I felt, quite fine in it.”

Taylor remembered that Shearer went out of her way to be kind to Alla Nazimova and insisted that “Nazimova could be very testy and temperamental: I don’t think she had faced, even past sixty, the fact that she was no longer the star and the centrepiece of whatever environment she found herself in. I found her a drag at times; in fact, she got on my nerves no end, but Norma was just wonderful with her.” Others agreed that Norma was a kind soul especially when she sensed tragedy or failure in another’s life.

Reviews for Escape were no worse than it deserved, or surprisingly good, depending on which biography you read, but for Nazimova, so it is written, rather better than she deserved, although it’s not entirely her fault if the performance seems exaggerated. As originally written, Emmy Ritter is a vain, superficial actress whose first request, after being rescued, is for a makeup kit. All she wants, after experiencing the darkest of realities, is to get back to the theatre. It was the story’s ironic edge, lost on the cutting-room floor, that attracted Cukor, and Nazimova cannot be blamed for playing one aspect of a character that was later eliminated. But at times LeRoy allowed her to overreact in silent-movie style, something that Cukor would surely have restrained.

You and I will certainly have our own thoughts on Nazimova’s skill as an actress, as well as whether Norma Shearer’s role feels superfluous or not.

The most interesting aspect of this film for me, is the fact that it’s one of the earliest of the many Hollywood films made about WWII during WWII, with Nazism and Hitler being a huge world-concern.

Sourced from Norma: The Story of Norma Shearer by Lawrence J. Quirk (1988); Norma Shearer by Gavin Lambert (1990); Nazimova: A Biography by Gavin Lambert (1997)

Introduction by Caren Feldman

A June, 1939 article in the film industry magazine Boxoffice tells the damning story of MGM Studios hosting a contingent of Third Reich newspaper editors on a “goodwill tour”. The Hollywood Anti-Nazi League (founded by communist spy Otto Katz with Donald Ogden Stewart and Dorothy Parker as the figureheads) “fumed” afterwards, but the whole affair was handled so surreptitiously that there was no time to organize a protest. In a separate article on the same page of this issue is a statement from Jack L. Warner, brashly declaring his “revolutionary type of picture” Confessions of a Nazi Spy to be “one of the most successful pictures Warner Bros. has produced this year” despite protests by those sympathetic to the Nazi cause. In 1933, Warner Bros. had boldly cut all ties with the German market when their Berlin branch manager, Phil Kaufman, had, according to Variety, “His automobile stolen by Nazis, his house ransacked, and himself beaten, despite the fact that he’s British.” Kaufman was Jewish, however, and Warner Bros., putting their morals over German money, became the first major studio to make openly anti-Nazi movies. On the other hand, MGM cautiously maintained their German market—they even employed Reich Minister of Foreign Affairs Konstantin von Neurath’s nephew in their Berlin headquarters. But the situation eventually became untenable, and by 1940, MGM had joined the propagandistic front by releasing The Mortal Storm, thus barring the studio from Germany. Escape continued this mode—shedding light on the Nazi menace in the studio’s imitable glossy sheen.

For the story of a man trying to smuggle his mother out of a concentration camp, MGM hired a screenwriter who was both familiar with suspense and fearlessly political. Arch Oboler is best known as the radio pioneer behind the horror series Lights Out (and specifically the bizarre episode “Chicken Heart”, wherein an exponentially-growing chicken heart engulfs the world) and the

producer/director of the Bwana Devil (which engulfed the world in 3-D movies). Besides a fantastic imagination, the Chicagoan born to immigrant Latvian Jews was passionately political. Prior to Pearl Harbor, he gave a fiery speech at Ohio State University, advocating violence against the Axis powers. He later recalled his insistence that the soldiers: “…must pull triggers and spill blood. And we at home needed the anger and the determination and the hate to enable us to endure the coming death of our sons and our fathers and our husbands.” The outlet for the dogmatic side of Oboler came out full bore in his radio series Arch Oboler’s Plays and later, Everyman’s Theatre, which featured performances by Escape stars Norma Shearer, Nazimova, and Conrad Veidt. Escape, based on a best-selling and serialized novel by Grace Zaring Stone, was his first screenplay in a fascinating, albeit uneven, foray into the film world.

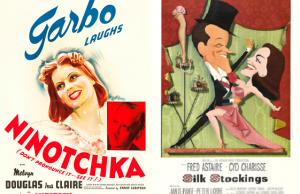

Norma Shearer, “The First Lady of MGM”, and Robert Taylor are the headliners, but it’s the rest of the cast that give Escape its emotional power. Nazimova had not appeared on screen since 1925—this was her first talkie performance, and it was memorable. Motion Picture Herald praised her: “Mme. Nazimova has not much to do but lie abed and manifest anguish, but in the few moments of activity allotted to her, …she displays her superb histrionic training.” Several escapees of the totalitarian Nazi state appear. In 1933, Conrad Veidt was faced with the ultimatum: divorce his Jewish wife and continue working in Germany, where he had been one of the most popular actors since the vivacious days of expressionism, or leave forever. In defiance of Joseph Goebbels dictums, Veidt claimed himself Jewish and fled with his wife. Escape was his first American film since 1929’s The Last Performance. Hedda Hopper described his appeal in the film: “…A walking menace, sex appeal, subtlety, and manhood wrapped up in one package if I ever saw it.” Felix Bressart would probably not get the same assessment—the gawky, Jewish-German émigré found a second life in the Hollywood community by playing charming roles by fellow ex-pats Henry Koster (Three Smart Girls Grow Up), Ernst Lubitsch (The Shop Around the Corner), and Fred Zinnemann (The Seventh Cross).

In 1933, the Militant League for German Culture issued the statement: “We likewise decline to tolerate on the German stage all those people who are still friendly with Jewish circles or are more or less married to them—be they ever such great talent.” Like Veidt, Albert Bassermann—a student of Max Reinhardt—resigned from the German stage when his Jewish wife, Elsa, was barred from performing based on this command. Despite arriving in the U.S. without speaking a word of English, he carved out an impressive career, including playing the kidnapped diplomat Van Meer in Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent and playing opposite Veidt in Cukor’s A Woman’s Face. Elsa made five more brief appearances in films alongside her husband before he died, in 1952.

The Los Angeles Times was slightly critical of the film, opining that it didn’t meet the level of the “bellwether examples” of the current slate of topical melodramas, Foreign Correspondent and Arise My Love. But Variety called it “excellent, suspenseful material” and complimented Mervyn LeRoy’s direction in creating “…a tense atmosphere of impending danger.…” The Washington Post’s Nelson B. Bell said Escape “…is perhaps the most shrewdly devised of all pictures that have assailed tyranny through the medium of tense and exciting entertainment.” Bosley Crowther concurred, “…This is far and away the most dramatic and hair-raising picture yet made on the sinister subject of persecution in a totalitarian land.”

Notes by Adam Williams

Leave a Reply