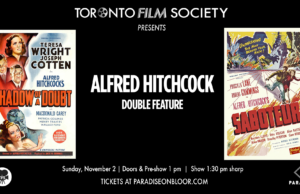

Sabotage (1936)

Toronto Film Society presented Sabotage (1936) on Saturday, February 28, 2026 as part of the Season 78 Virtual Film Buffs Screening Series, Programme 3.

Production Company: Gaumont-British. Producer: Michael Balcon. Director: Alfred Hitchcock. Screenplay: Charles Bennett, based on the book The Secret Agent by Joseph Conrad. Cinematography: Bernard Knowles. Editor: Charles Frend. Music: Jack Beaver. Running Time: 76 minutes. Released December 2, 1936 in London.

Cast: Sylvia Sidney (Mrs. Verloc), Oscar Homolka (Karl Verloc), Desmond Tester (Stevie), John Loder (Detective Sgt. Ted Spencer), Joyce Barbour (Renee), Matthew Boulton (Superintendent Talbot).

Alfred Hitchcock’s 1936 film Sabotage sits in a fascinating and slightly uncomfortable corner of his filmography. Made during his British period, before his move to Hollywood and the global recognition that would follow, the film reveals a director who already understood audience psychology at an almost surgical level, but who was still willing to take emotional risks he would later pull back from. Loosely inspired by Joseph Conrad’s novel The Secret Agent, the film transforms what could have been a conventional political espionage story into something much more intimate and unsettling: a portrait of terrorism that exists not in distant battlefields or secret government rooms, but inside everyday life.

Watching the film today, what feels most striking is not just its suspense mechanics, but how modern its emotional and thematic concerns feel. Sabotage is not really about espionage. It is about proximity to violence. It is about what happens when danger is not “out there,” but already embedded in the spaces we trust the most.

The film was produced during a crucial moment in Hitchcock’s career. By the mid-1930s, he was already one of the most respected directors working in Britain, following the success of films like The 39 Steps. The British film industry itself was going through a complicated transition, trying to compete with the growing dominance of Hollywood while also developing its own identity. Studios like Gaumont-British, where Hitchcock was working at the time, were investing heavily in prestige productions that could travel internationally. Hitchcock had already proven he could deliver commercial hits, but he was also gaining a reputation for pushing stylistic and narrative boundaries. Sabotage emerged in this environment, at a time when political anxiety was rising across Europe, even if the full scale of what was coming with World War II was not yet fully understood by the public.

The source material also matters in understanding the film’s tone. Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent, published in 1907, was already a deeply cynical exploration of political extremism, surveillance, and bureaucratic indifference to human life. Conrad wrote it partly in response to anarchist movements operating in Europe at the turn of the twentieth century. Hitchcock and his collaborators significantly altered the story, stripping away much of the political complexity and focusing instead on the emotional consequences of sabotage. That shift is telling. Hitchcock was never primarily interested in political ideology; he was interested in human behavior under pressure. By reframing Conrad’s story into something more domestic and emotionally intimate, he made the narrative more accessible, but also more disturbing.

The story centers on Karl Verloc, a London cinema owner who is secretly part of a sabotage network, and his wife, who lives inside this reality without knowing it. What makes the film particularly powerful is that Hitchcock is not interested in turning Verloc into a theatrical villain. He is not charismatic in a traditional cinematic way, nor is he written as a mastermind driven by grand ideology. Instead, he is disturbingly ordinary. That ordinariness becomes the film’s most unsettling element. Hitchcock is not asking the audience to fear an obvious monster. He is asking us to confront the idea that violence can live quietly inside normal routines, inside familiar relationships, inside spaces we associate with comfort. In 1936, this was already provocative. From a contemporary perspective, it feels almost prophetic.

Hitchcock grounds the film in environments that feel safe and communal: a neighborhood cinema, a modest apartment, crowded city streets, public transportation. These are not symbolic spaces. They are recognizably lived-in spaces. The choice is crucial because it reframes sabotage not as a political act, but as an emotional and social rupture. The film is less concerned with the logistics of terrorism and more concerned with its ripple effects on ordinary people who have no agency in these larger systems of violence. That shift in perspective gives Sabotage a moral weight that separates it from many thrillers of its time, and arguably even from some thrillers today.

The emotional center of the film is not Verloc. It is his wife. Hitchcock gradually shifts the audience’s alignment toward her experience, turning the story into something closer to a domestic tragedy than a traditional suspense narrative. What we watch unfold is not just the exposure of a crime, but the collapse of trust inside an intimate relationship. Hitchcock would explore themes of guilt, secrecy, and emotional betrayal throughout his career, but here they feel unusually raw. There is less stylistic distance between audience and character suffering. The emotional consequences are not softened or stylized. They are simply allowed to exist.

The film is most famously associated with its bus sequence, which has become central to discussions about Hitchcock’s evolving philosophy of suspense. Hitchcock often described suspense using what became known as the “bomb under the table” principle: if a bomb suddenly explodes under a table where characters are sitting, the audience feels shock for a few seconds. But if the audience knows the bomb is there and watches characters talk around it, tension builds over time. In Sabotage, Hitchcock pushes this idea into morally dangerous territory. Instead of using audience knowledge to create prolonged tension followed by safe release, he allows the worst possible outcome to occur. The result is not simply suspense. It is emotional devastation.

At the time of its release, this moment deeply divided critics and audiences. Some reviewers praised the film’s intensity and realism, while others found it excessively cruel. British critics in particular were split, with some arguing that Hitchcock had sacrificed narrative pleasure for shock value. The controversy was significant enough that it followed Hitchcock for years. He later spoke openly about feeling that he had made a mistake, suggesting he had broken the unspoken agreement that audiences expect some level of moral protection in mainstream storytelling. Yet that same choice is part of why the film has remained so critically interesting. What may have felt like a miscalculation in 1936 now reads as a daring refusal to soften the emotional consequences of violence.

Commercially, the film performed solidly but was not considered one of Hitchcock’s major hits at the time. It did not have the same broad appeal as some of his more straightforward thrillers. However, it helped solidify his reputation as a director willing to experiment with tone and audience expectations. This reputation ultimately contributed to the growing interest from Hollywood studios, who saw him as both commercially viable and artistically distinctive. Within a few years, he would leave Britain and begin the Hollywood phase of his career that would produce many of his most famous films.

Another aspect that feels remarkably contemporary is how the film treats ideological violence as something that ultimately destroys personal lives more than political systems. Hitchcock is not interested in giving the saboteurs grand speeches or complex ideological frameworks. Their motivations feel abstract and distant compared to the very tangible emotional damage their actions create. The focus remains firmly on the human cost. This is one of the reasons the film resonates differently than many propaganda-adjacent thrillers of the 1930s. It does not try to convince the audience of a political position. Instead, it asks us to confront emotional consequences.

From a craft standpoint, the film is fascinating because you can see Hitchcock in transition. The visual storytelling is already precise. His understanding of spatial geography, crowd tension, and environmental storytelling is clearly developed. His editing rhythms already demonstrate an instinct for psychological pacing rather than purely narrative pacing. At the same time, the film still carries some of the rawness of his British period work. It is less polished than his later Hollywood films, but arguably more emotionally volatile. There is a sense that Hitchcock is testing how far he can push audience discomfort before it becomes alienating.

What also makes the film compelling today is how it reflects an anxiety that feels incredibly current: the fear that violence is not an external threat but something woven into daily life. Modern audiences are, unfortunately, very familiar with this emotional reality. The idea that public spaces, transportation systems, and entertainment venues can become targets is no longer abstract. In that sense, the film has aged not as a historical artifact, but as a strangely relevant emotional document. It reminds us that the psychological impact of terrorism is not only about destruction, but about destabilizing our sense of safety in ordinary environments.

Within Hitchcock’s larger career, Sabotage feels like a bridge between two creative identities. It has the visual discipline and urban realism of his British films, but it also hints at the emotional manipulation and psychological layering he would later perfect in Hollywood. What it lacks in polish, it makes up for in daring. It is a film that is willing to make the audience deeply uncomfortable without offering easy emotional recovery.

Nearly ninety years after its release, Sabotage remains a powerful reminder that suspense is not just about plot mechanics. At its best, suspense is about emotional investment, moral tension, and the fear of irreversible consequences. Hitchcock would go on to become synonymous with technical mastery and narrative control, but films like Sabotage reveal another side of him: a filmmaker willing to take creative risks that challenge not just characters, but audiences themselves.

If Hitchcock’s later masterpieces represent the perfection of suspense as entertainment, Sabotage represents suspense as emotional confrontation. It asks viewers to sit with discomfort, to question their assumptions about narrative safety, and to recognize that the most frightening threats are often the ones that exist closest to home. That willingness to disturb, rather than simply entertain, is what ultimately makes Sabotage one of the most fascinating – and quietly radical – works of Hitchcock’s early career.

Notes by Leandro Matos

Virtual Saturday Night at the Movies

Toronto Film Society will be screening Sabotage (1936) straight to your home on Saturday, February 28, 2026 at 7:30 p.m. (ET)! Directed by Alfred Hitchcock, starring Sylvia Sidney, Oscar...