Song of Ceylon (1934-35) and Le Sang D’Un Poete [Blood of a Poet] (1930)

National Film Society – Toronto Branch presented Song of Ceylon (1934) on Monday, November 28, 1949 in a double bill with Sang D’Un Poete (1930) as part of the Season 2 Main Series, Programme 3.

NATIONAL FILM SOCIETY TORONTO BRANCH

3rd EXHIBITION MEETING, 1949-50 SEASON

November 28th, 1949 8:15 P.M.

Royal Ontario Museum Theatre

Schedule: – Song of Ceylon – INTERMISSION – Opening Remarks by Roy Clifton – Introduction to the film by Mr. Herman Voaden – Blood of a Poet – Discussion: Mr. Herman Voaden and Mr. Eric Aldwinckle – Members’ Participation.

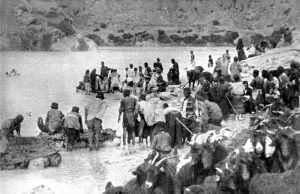

Song of Ceylon (Great Britain, 1934-35) Source: N.F.S. Ottawa Running Time 45 Minutes

DIRECTION: Basil Wright

ASSISTANT: John Taylor

SOUND: Alberto Cavalcanti

MUSIC: Walter Leigh

PRODUCED by John Grierson with the Ceylon Tea Propaganda Board

Asked which of his films was his favourite, John Grierson replied in a letter in the Vancouver Branch of the National Film Society, 1939:

“Song of Ceylon was a sport among documentary films. It was a more personal job than the others. Basil Wright and I had been very continuously occupied for years shaping this and that film to a specific occasion and being altogether practical and sensible. When the Ceylon film came along, we were somewhat inclined to go off the earth. Everyone was howling for speed and they had a case; for English films are inclined to be slow and the medium is a very physical medium with a love for railroad trains in spirit and in form.

We were inclined to go off on the other foot and say for once: “we are going to be as slow as we like and maybe the medium can be contemplative too. Maybe this craving for film speed is only a movie fever or habit, formed by a continuous diet of the brilliant speed and physicalities of Hollywood films.” We realised, of course, that we might be going against nature but nevertheless it was our mood to rest up on a film and, as in poetry, music, painting and the other decent arts, we asked the audience to quieten its spirit and be at peace. We thought an audience might for once sit there in peaceful interchange with the screen, bringing to the screen as much as it was given.

That again might be interpreted as saying: “Damn the public: if they won’t come half way, so much the worse for them.” Certainly you will find a certain rude hammering of the public’s head in Song of Ceylon. But the point to take is that the film was a personal film and essentially one which we made to please ourselves. One should also remember that it was made some years ago and that we were a bunch of experimentalists who had just acquired their first sound recording apparatus. As things go now, it was a primitive mechanism, but we were nonetheless anxious to try out some of the notions and refinements of sound technique which came up in the first fine careless rapture of sound enthusiasm. I have not seen the film for a long time and I only hope that some of our rapture will be audible through the ground noise. The great talent which was with us in our sound experiments was Cavalcanti who has been as great a pioneer and experimentalist in sound as he was a pioneer of the silent film.

You will see that the film of Song of Ceylon reflects our approach. The form is basically a musical one. The theme is Buddhism and the art of life it has to offer, set upon by a Western metropolitan civilization which, in spite of all its skills has no art of life to offer. There are four movements. The first and second indicate the human harmony which an art of life signifies. The third movement indicates the opposition of the two spiritual forces. The fourth movement indicates that whatever the material solution of Ceylon’s problem may be, the spiritual one is certainly in the maintenance of achievements of an art of life. We make our point by re-emphasizing the dignity and even the gaiety of the religious theme. In certain strange boomings of sound we try to say again, with all effect, that the fear of God is the crown of wisdom. You will appreciate of course, that we were not concerned with Buddhism per se as with the art of life per se. It so happened that in Ceylon we found magnificent visual material for making our point.

We have had this comfort from the film that many have said that it is one of the few truly religious films ever made. If you are quiet with the film (Operator, please pile up the great gong crashes at the end to deafen their ears and quieten off the sound to nothing the moment the final leaves open on the screen) you too may find it so. Your operator must also guild up the savage drums at the beginning and quieten off on the idyllic passages and build up again on the religious drums at the end. Playing the film in this way is important, for as I said, it is one of these films you can feel personal about and in which you can make your own emphasis.

Some technical points may be interesting to know. Walter Leigh was the composer and, technical roughness of sound apart, you may find an element of distant beauty at the beginning of the last movement where the little man comes in from the horizon to pray and Wright’s deliberation of cutting waits on the music. We were interested then in the capacity of sound to make ironical comment on the images. You will find this in the radio signals which overlay the face of Buddha. You will find it again in the commercial sequence where the chatter of financial and commercial rigmarole overlays idyllic Ceylon. You will find it again where the voice attendant on the native who prays to his god before climbing for copra is saying: “Yours faithfully, yours faithfully, yours faithfully.”

There may be a point of interest too in the commentary, for it was taken solidly from one of the most ancient accounts of Ceylon, and it is spoken as we thought right by a voice which added a slightly exotic or abstract note to the already archaic style of the prose. Psychological distance seemed important when we made this film and we sought its terms assiduously. We were very conscious then that, whatever sound had brought to the film in new vitalities and powers of expression, there was a deep virtue in the silence of the silent film for which a sound equivalent had to be found. You will see one highly ambitious image of distance in the dawn sequence, where the clatter of religious gongs wakes the bird from the tree and it flies swooping and fading, swooping and fading, across the whole of Ceylon. You will find the same search for an image of distance in sound where, in creating a leit motif for the Buddha and religion, we caught the note of a gong in another close by, trucked in the microphone and made the boom of the dying reverberations louder than the crash. The full effect was obtained by doing this twice and reversing the first sound track so that, as we thought the sound might seem to come out of the stomach of the audience, pass the screen, crash, and come back again. This was done on different notes. I have not heard the effect for a long time but when we first presented the film, and the sound projectionists played it really high, it did to the Film Society at the Tivoli in London what we wanted it to do. It put them physically beyond criticism. This may not be a bad thing to do, occasionally, with any Film Society. The grasshopper twitterings of the critical mind, the local chatterings in the grass are by no means the deepest form of experience.”

INTERMISSION 10 minutes

Mr. Roy Clifton will introduce Mr. Herman Voaden who will introduce the film.

Le Sang D’Un Poete (Blood of a Poet) France, 193? Source: N.F.S. Ottawa Running Time 55 minutes

DIRECTION: Jean Cocteau

MUSIC: George Aurie

EDITOR: Jean Wiedmer

SPECTACLE MONTAGE: Jean Cocteau

TECHNICAL DIRECTION: Michel J. Arnaud

PHOTOGRAPHY: George Perinal

SOUND ENGINEER: Henri Labrely

ASSISTANT: Louis Page

ASSISTANT OPERATOR: Preben Engeberg

DECORATOR: Jean Gabriel D’Eaubonne

ORCHESTRA LEADER: Edouard Flament

PLASTER DESIGNS by Plastikos

TRANSLATION OF PREAMBLE which appears on title at beginning of film–“Every poem is a coat of arms. It is necessary to decipher it. What blood, what tears in exchange for these axes, faces, unicorns, torches, these martlets, for these star-studded fields of blue.

Free to choose the faces, the shapes, the gestures, sounds, acts, places which he likes–with them he creates a realistic documentary of unreal happenings. The musician will underline the sounds and the silences.

The author dedicates this film of allegories to the memory of Pisanello, Paola Uccelo, Piero della Francesco, Andrea del Castagno, painters of crests and enigmas.”

TRANSLATION OF FIRST SUBTITLE (which occurs midway through the opening sequence)–“Snatched out of a picture like a leper by the naked hand, the drowning mouth seemed to dissolve into a little zone of white light.”

TRANSLATION OF THE SECOND SUBTITLE and also of the THIRD which follows immediately, in Cocteau’s own handwriting. The second title reads–“The close-up of the sleeper or the surprises of photography.”

The third title reads: “….or of how I was trapped by my own film–Jean Cocteau”

______________________________________________________________________

Blood of a Poet is a mystifying film yet it has practically played stock at the 5th Avenue Playhouse in New York for many years. As an example of the avant-garde film movement in France, it is considered to be “required reading” for film societies.

It was the first film of Jean Cocteau–playwright, novelist, draughtsman, sculptor, choreographer, essayist, philosopher and poet–as well as film maker. It is not in the least resembled by his film Beauty and the Beast, now on view at the International Cinema.

Cocteau himself called the film a poem on celluloid and about it he says, “I am trying to picture the poet’s inner self.”

The film opens with a scene showing the start of the collapse of a huge smokestack. It closes with a similar scene showing the completion of the downfall. All that occurs in the film is supposed to transpire in the time taken for the chimney to fall. The film is divided into four episodes:—

- THE WOUNDED HAND, or THE POET’S SCARS.

- DO WALLS HAVE EARS?

- THE BATTLE OF THE SNOWBALLS.

- THE PRFANATION OF THE HOST.

Some of the symbols would seem to admit of reasonably straightforward interpretations. Two which do not, are the star on the poet’s left shoulder and the suit of balls worn by the child in the second episode. The star is Cocteau’s personal habitual sign. As for the suit of bells, in past times it was the custom when training children to be thieves to make them wear such a suit so that they would learn to move silently. The incident in which this occurs shows the cruel stepmother giving such a lesson. Interpretation of this is left to the audience.

THE BLANK pieces of film accompanied by sound track: We do not know if Jean Cocteau designed the sequence in this way or if it is an example of French censorship. It is certain that it has nothing to do with American censorship, as this print was purchased in Paris. If anyone wo has seen the film in Europe can help us with this point, we would be grateful.

Cocteau’s statement concerning his own interpretation of the film will be distributed to the members after the showing. (Notes Page #5.)

______________________________________________________________________

THE DISCUSSION on Blood of a Poet will be by Mr. Herman Voaden, Canadian dramatist and play-producer and Mr. Eric Aldwinckle, Canadian artist.

Mr. Voaden will defend the film as a work of art while Mr. Aldwinckle will challenge the validity of the surrealist and naturalist aspects of art as exemplified in this film. (If possible this discussion will be recorded on tape for use by other Branches.)

______________________________________________________________________

IN THE LOBBY 7.45 TO 8.10 p.m. EXPLORING GEORGIAN BAY by Dr. A. D. Pollock (Ontario, 1941) 1 1/2 reels silent colour film. Records a trip from Owen Sound along the coast of Bruce Peninsula to Tobermory. The film contains unusual scenes of natural life.

DISPLAY OF PERIODICALS on the film. It will be possible for members to subscribe to WEQUNCE, IMPACT, CANADIAN FILM NEWS this evening.

MUSIC FOR TONIGHT–from the sound track of Indian Films: before performance. Darius Milhaud – PROTEE Symphonic, Suite No. 2: at Intermission.

BEAUTY AND THE BEAST: As the International Cinema has obtained a 35mm print of this film, the Programme Committee feels that the members would see it to better advantage there, in the large size and with English titles, and therefore propose to spend the Society’s funds on a different programme instead.

NEXT EXHIBITION MEETING: December 13 – Harry Watt’s Bush Christmas – Charlie Chaplin’s The Bank – Norman McLaren’s Boogie Doodle, Hoppity Pop.

Leave a Reply