The Eagle and the Hawk (1933)

By Toronto Film Society on June 28, 2025

Toronto Film Society presented The Eagle and the Hawk (1933) on Monday, July 7, 1986 in a double bill with To Each His Own as part of the Season 39 Summer Series, Programme 1.

Production Company: Paramount. Director: Stuart Walker. Assistant Director: Mitchell Leisen. Screenplay: Bogart Rogers and Seton Miller from a story by John Monk Saunders. Cinematography: Harry Fischbec.

Cast: Frederic March (Jerry Young), Cary Grant (Henry Crocker), Jack Oakie (Mike Richards), Carole Lombard (The Beautiful Lady), Sir Guy Standing (Major Dunham), Adrienne D’Ambricourt (Fanny), Forrester Harvey (Hogan), Kenneth Howell (John Stevens), Leyland Hodgson (Kingsford), Virginia Hammond (Lady Erskine), Crauford Kent (General), Douglas Scott (Tommy), Robert Manning (Major Kruppman), Russell Scott (Flight Sergeant), Olaf Hytten, Lane Chandler, Dennis O’Keefe, York Sherwood, Paul Gremonesi.

In 1927, William A. Wellman’s Wings kicked off a cycle of World War I aviation films. Some of the best–1930’s The Dawn Patrol and 1931’s The Last Flight–were written by former World War I flying ace John Monk Saunders. In 1933, however, when Saunders wrote the story on which The Eagle and the Hawk is based, the cycle was beginning to lose its momentum. Variety commented on the film’s release that it was “handicapped by the mass of earlier flight pictures.” This may explain why the film’s writers felt free to give it an unusually grim ending.

The plot of the film concerns a World War I pilot who begins to snap under the strain of losing too many of his fellow crew members. Frederic March plays the role of the pilot, while Cary Grant is his cynical, wisecracking rival for glory. Carole Lombard appears briefly as a girl March meets on leave in London, in what Variety felt was “a laboriously dragged in romantic bit to get a feminine star’s name on the program.” All three were at the start of their careers here and demonstrate both their own talent and Leisen’s skill in directing. They succeed in lifting the film’s melodramatic structure out of the ordinary and creating from it a movie which is tight, compact and compelling. William K. Everson comments: “There are certain cliches in this kind of fare that would be missed were they not there: the toasting of the enemy, the tactless batman, chattering about his ‘gentlemen’ who have been shot down, and that wonderful old professional Englishman Sir Guy Standing underplaying everything. ‘Seems a pity…’ he murmurs after an entire squadron of replacements has been wiped out by one bomb. But cliches or not, the film holds up well, surprisingly so considering the number of World War II films (Command Decision, Twelve O’Clock High) that explored the same situations rather more thoroughly.” The film’s durability may be due in part to its pacifist stance–its ending is distinctly “anti-hero” and tries to exposes war as a dirty business. This outlook seems to have been approved by the audiences of 1933–the New York Times reviewer found the film “devoid of the stereotyped ideas which have weakened most of such narrations” and Variety felt the ending was “neatly turned, unexpected and comes at a point where it gives impetus to an idea which seems to be closing in with a ‘just another’ tag.”

The Eagle and the Hawk was Mitchell Leisen’s second film with Stuart Walker as his co-director and it was this film that finally convinced Paramount to let Leisen begin his solo career with Cradle Song (1933). Leisen was to remain one of the studio’s most consistently successful directors throughout the 30’s and 40’s, when every one of his films made money for the studio. Some critics have attributed Leisen’s unbroken success to an unwillingness to move in new directions or take chances with his material–he succeeded, they argue, because he never aimed very high. John Gillett is kinder in his assessment: “Leisen worked best when surrounded by the finest writing and technical talents, moulding them together into a seamless whole and never apparently obtruding his own personality: yet the films’ very precision and economy testify to the effectiveness of his ‘invisible’ direction.”

Notes by Laurie McNeice

You may also like...

-

News

Thank You from TFS!

Toronto Film Society | July 21, 2025Our matinée on Sunday, August 17th – at the blessedly air conditioned Paradise Theatre – will conclude the Toronto Film Society’s 77th season! But take heart, as we’ll be...

Programming

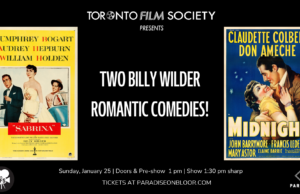

Sunday Afternoons at the Paradise

Toronto Film Society | January 25, 2026Join TFS for Season 78’s Sunday Matinée Series generously sponsored by our good friend, author and documentary filmmaker, Mr. Don Hutchison. Please save this date and visit us regularly...

-

Toronto Film Society | January 25, 2026

Toronto Film Society | January 25, 2026

-

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

-

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Donate to Toronto Film Society – We’re now a Registered Charity!

Copyright © 2017 Toronto Film Society.