The Searchers (1956)

Toronto Film Society presented The Searchers (1956) on Monday, December 3, 1979 in a double bill with Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde as part of the Season 32 Monday Evening Film Buff Series, Programme 4.

Distributor: Warner Brothers. Production Company: C.V. Whitney Pictures, Inc. Executive Producer: Merian C. Cooper. Associate Producer: Patrick Ford. Director: John Ford. Script: Frank S. Nugent, from the novel by Alan LeMay. Photography: Alfred Gilks. Editor: Jack Murray. Art Direction: Frank Hotaling, James Basevi. Set Direction: Victor Gangelin. Music: Max Steiner. Orchestration: Murray Cutter. Title Song: Stan Jones, sung by The Sons of the Pioneers. Sound: Hugh McDowell, Howard Wilson. Wardrobe: Frank Beetson, Ann Peck. Production Supervisor: Lowell Farrell. Assistant Director: Wingate Smith. Locations: Monument Valley, Utah-Arizona; Gunnison, Colorado; Alberta, Canda.

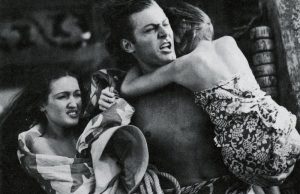

Cast: John Wayne (Ethan Edwards), Jeffrey Hunter (Martin Pawley), Vera Miles (Laruie Jorgensen), Ward Bond (Captain Rev. Samuel Clayton), Natalie Wood (Debbie Edwards), John Qualen (Lars Jorgensen), Olive Carey (Mrs. Jorgensen), Henry Brandon (Chief Scar), Ken Curtis (Charlie McCorrey), Harry Carey, Jr. (Brad Jorgensen), Antonio Moreno (Emilio Figueroa), Hank Worden (Mose Harper), Lana Wood (Debbie, as a child), Walter Coy (Aaron Edwards), Dorothy Jordan (Martha Edwards), Pippa Scott (Lucy Edwards), Pat Wayne (Lieutenant Greenhill), Bill Steele (Ranger Nesbitt), Cliff Lyons (Colonel Greenhill), Beulah Archuletta (Look), Jack Pennick (Private), Peter Mamakos (Futterman), Chuck Roberson (Texas Ranger), Billy Carledge, Chuck Hayward, Slim Hightower, Fred Kennedy, Frank McGrath, Dale VAn Sickle, Henry wills, Terry Wilson (stuntment), Away Luna, Billy Yellow, Bob Many Mules, Exactly Sonnie Betsuie, Feather Hat, Jr., Harry Black Horse, Jack Tin Horn, Many Mules Son, Percy Shooting Star, Pete Gray Eyes, Pipe Line Begishe, Smile White Sheep, and other members of the Navajo tribe (Commaches), Mae Marsh, Dan Borzage.

Shooting from mid-June to mid-August, 1955. Released in USA March 13, 1956.

“It’s the tragedy of a loner. He’s the man who came back from the Civil War, probably went over into Mexico, became a bandit, probably fought for Juarez or Maximilian–probably Maximilian, because of the medal. He was just a plain loner–could never really be a part of the family.” – John Ford

Is there any more American film than The Searchers, any work that more concisely sums up the dichotomy in American consciousness between the pioneer and the businessman, the soldier and the farmer? In its extraordinary economy, its efficiency of technique, the memorable playing of its principals and supporting cast it is perhaps Ford’s most perfect philosophical statement. …The deep thinking of The Searchers is subliminal, carried on in the Ford language of gesture, visual metaphor and action which he uses for his most personal statements.

The Cinema of John Ford by John Baxter, Zwemmer/A.S. Barnes, 1971

The Searchers has that clear yet intangible quality which characterizes an artist’s masterpiece–the sense that he has gone beyond his customary limits, submitted his deepest tenets to the test, and dared to exceed even what we might have expected of him. Its hero, Ethan Edwards (John Wayne), is a volatile synthesis of all the paradoxes which Ford had been finding in his Western hero since Stagecoach. A nomad tortured by his desire for a home. An outlaw and a military hero. A cavalier and a cut-throat. Ethan embarks on a five-year odyssey across the frontier after his brother’s family is murdered and his niece taken captive by the Comanches. Like Ulysses, he journeys through a periolous and bewitching landscape. Even more than in Ford’s earlier Westerns, the land is felt as a living, governing presence.

John Ford by Joseph McBride and Michael Wilmington, Da Capo, 1975

What Ford had been evolving all through his career was a style flexible enough to establish priorities of expression. He could dispose of a plot quickly and efficiently when he had to, but he could always spare a shot or two for a mood that belonged to him and not to the plot. A Ford film, particularly a late Ford film, is more than its story and characterizations; it is also the director’s attitude toward his milieu and its codes of conduct. There is a fantastic sequence in The Searchers involving a brash frontier character played by Ward Bond. Bond is drinking some coffee in a standing-up position before going out to hunt some Comanches. He glances toward one of the bedrooms, and notices the woman of the house tenderly caressing the Army uniform of her husband’s brother. Ford cuts back to a full-faced shot of Bond drinking his coffee, his eyes tactfully averted from the intimate scene he has witnessed. Nothing on earth would ever force this man to reveal what he had seen. There is a deep, subtle chivalry at work here, and in most of Ford’s films, but it is never obtrusive enough to interfere with the flow of the narrative. The delicacy of emotion expressed here in three quick shots, perfectly cut, framed, and distanced, would completely escape the dulled perception of our more literary-minded film critics even if they deigned to consider a despised genre like the Western. The economy of expression that Ford has achieved in fifty years of film-making constitutes the beauty of his style. If it had taken him any longer than three shots and a few seconds to establish this insight into the Bond character, the point would not be worth making. Ford would be false to the manners of a time and a place bounded by the rigorous necessity of survival.

The American Cinema by Andrew Sarris, Dutton & Co., 1968

The dramatic struggle of The Searchers is not waged between a protagonist and an antagonist, or indeed between two protagonists as antagonists, but rather within the protagonist himself. Jeffrey Hunter’s surrogate son figure in The Searchers is the witness to Wayne’s struggle with himself rather than a force in resolving it. The mystery of the film is what has actually happened to Wayne in that fearsome moment when he discovers the mutilated bodies of his brother, his beloved sister-in-law, his nephew, and later his niece. Surly, cryptic, almost menacing even before the slaughter, he is invested afterwards with obsession and implacability. We in the audience never see the bodies or the actual slaughter, only the smoke passing across Wayne’s contorted countenance at the moment of discovery, a cosmic composition of man ravaged by revenge-seeking emotions in the aftermath of an atrocity; but that cosmic composition, reprinted so often in specialized film magazines, never breaks the flow of action, but instead accelerates the development of characters, and cracks open, as violence traditionally does in drama, all their massively encrusted psychological secrets.

The John Ford Movie Mystery by Andrew Sarris, Secker & Warburg, 1976

Not since The Quiet Man (1952) had Wayne taken on a part which really displayed his acting abilities, …Wayne liked his part of Ethan Edwards so much that he has named one of his sons Ethan, and his affection is fully understandable. It was an extremely difficult assignment to fully realise the character: it goes beyond Wayne’s basically powerful screen presence, beyond what he says, the way he looks and acts most of the time, and demands a communication of interior feelings that have to be sensed burning inside the man even while he appears open and relaxed. The result is unforgettable.

John Wayne and the Movies by Allen Eyles, Tantivy Press/A.S. Barnes, 1976

Wayne is fascinating for his sheer hardness. There’s no kindness in his nature–he is crafty and arrogant, and his eyes are cold as ice.

New York Herald Tribune by William K. Zinsser

Leave a Reply