Fifty Years in Film: 1947-1997

Fifty Years in Film

1947-1997

Impressions, Perceptions, Memories

Gerald Pratley

First President

and

Benjamin Viccari

Douglas Davidson

Stanley Fox

Edgar Jull

Fraser Macdonald

and

Patricia Thompson

William Sturrup

Dedicated to Eugenia Webb

Published by Toronto Film Society

with Cine-Communications, Toronto

Copyright 1999

A collaboration between

Gerald Pratley and Patricia Thompson

************************************

Presidents of the TFS

1948-50 Gerald Pratley

1951-52 Nola Goldaway

1952-54 Philip Budd

1954-55 Mary Axten

1956-57 Myrtle Virgo

1957-59 Roy Little

1960 Eugenia Webb

1961-62 Myrtle Virgo

1963-70 Ronald Anger

1971-77 Edgar Jull

1978-83 Jaan Salk

1984-88 Barrie Hayne

1989-96 Barry Chapman

1997-99 William Sturrup

Patrons

The Hon. Pauline M. McGibbon

Christopher Chapman

Graeme Ferguson

Norman Jewison

Aldo Maggiorotti

Gerald Pratley

The Many and Varied Cinemas, Theatres, Halls in which TFS has shown its films over the Past Fifty Years …

Royal Ontario Museum

The Christie

New Yorker

The Odeon Hyland

Vaughan

Century

Kent

Towne Cinema

The United Church

Auditorium of the North York Collegiate

Metro Cinema

St. Lawrence Centre

The Town Hall

Ontario Institute in Studies for Education (OISE)

Cinema Lumière

Ontario Film Theatre (Ontario Science Centre)

George Ignatieff Hall (U of T)

Euclid Theatre

John Spotton Cinema (NFB)

Central YMCA

Jackman Hall (AGO)

It is estimated that the TFS has shown over the past 50 years more than 10,000 films of all kinds.

************************************

Toronto Film Society

50th Anniversary – 97/98 Season

by Gerald Pratley

……………………………………………………………………………………

In the beginning we were The Toronto Film Study Group; then the National Film Society – Toronto Branch; then, finally, Toronto Film Society. And in the beginning, I was elected President of the Board of Directors which seemed rather high-flown at the time. I would rather have been known as the Chairman of what was possibly the first hard-working and enthusiastic group of individuals to dedicate themselves to film appreciation in Toronto. We all had a burning desire to bring to the public, and to see for ourselves, the classics from Europe, the best of the Silent Period, the great documentaries. And, of course, Canadian films–what little there were–from the National Film Board and Budge and Judith Crawley. It should be remembered that, in the outside world of movie theatres, the specialised or repertory cinema did not exist in Toronto at this time.

As a continuity writer at CBC Radio in 1948, I began a program of film reviews called This Week at the Movies, the first of its kind on radio, on DJBC. If memory serves me correctly, this brought a telephone call from Dorothy Burritt of the Toronto Film Study Group (TFSG). She and her husband Oscar had moved to Toronto from Vancouver and were determined to start a film society. As one did not “do lunch” in those days, I was invited to her house at 233 Grenadier Road, near High Park, to meet them and other enthusiasts. They discovered that I had been a member of the London Film Society, run by the indomitable Gwyneth Vaughan, and had been to showings by many smaller groups around London, held in libraries and municipal buildings during the darkness of wartime winter nights, and I was received as a celebrity from a faraway paradise of magnificent movies!

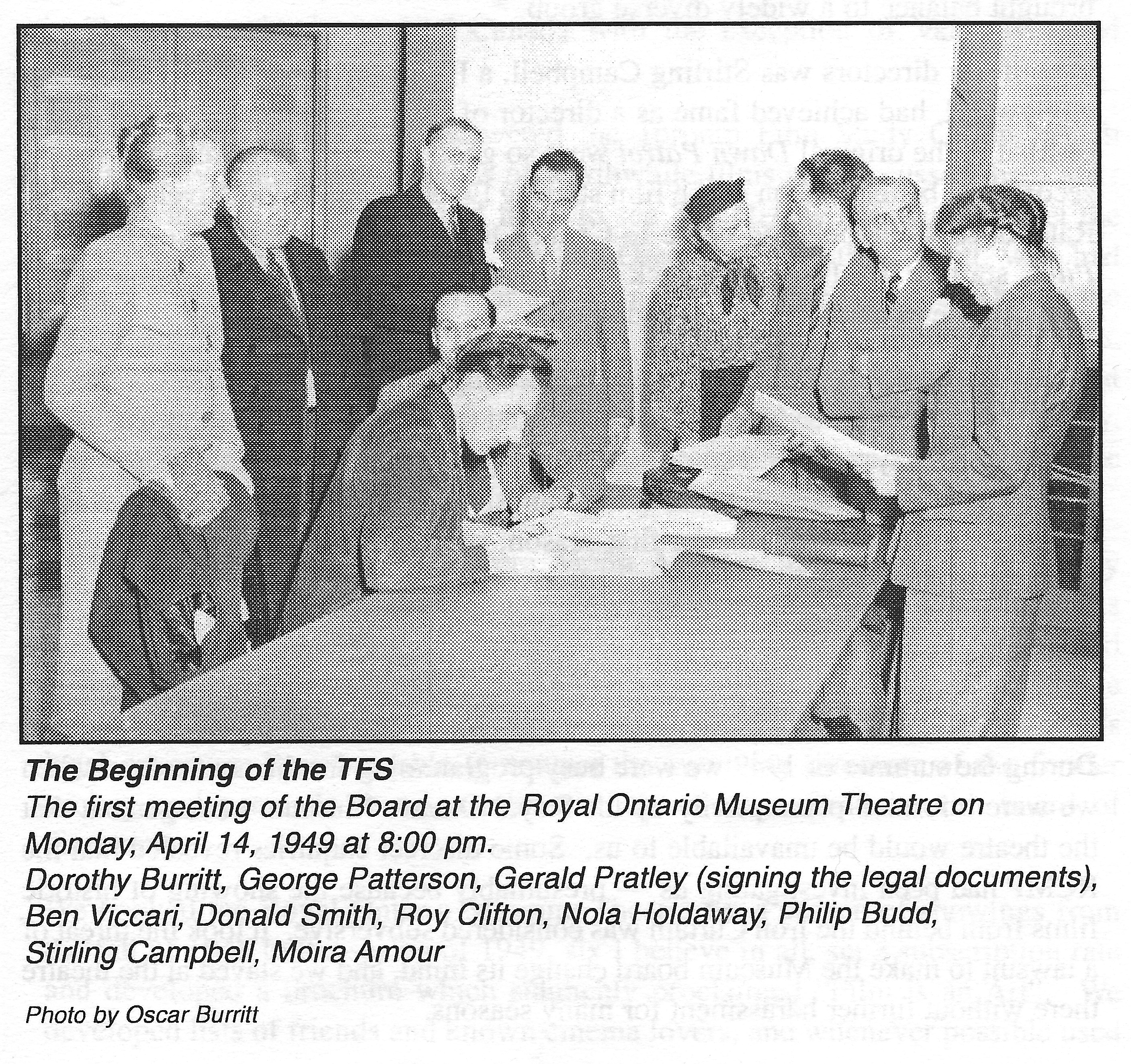

So began my five-year tenure as part of a friendly and knowledgeable group, several of whom also came from the UK. The first summer series of TFSG had been planned in part by Dorothy, to begin on April 25, 1948. The other members of the Board were Roy Clifton, Philip Budd, Moira Armour, George Patterson, Benjamin Viccari, Donald Smith, Nola Holdaway and Stirling Campbell. We all slipped quite naturally into the British tradition of setting up a society in which those involved worked for a cause they believed in, and whose remuneration came in its success. We were being amateurs in the finest sense of the word. Later, in New York City, William K. Everson (coming from London) set up the Theodore Huff society working under the same principles and for the love of film.

This first series of films was a beginning I look back on with pleasure and affection. We were close, harmonious and pioneering. We felt we had a mission to bring the work of famous and unknown filmmakers to the screen. Although I was the “prez” our direction emanated from Dorothy Burritt, on programming, and we met regularly in her spacious home to talk about films we had seen. Among us there was no more ardent filmgoer than George Patterson, who in later years wrote current film notes and reviews as part of the program notes. Dorothy served endless cups of tea, sandwiches and cakes, with wine on very special occasions. Although we were deeply serious about what we were doing we had many moments of merriment. Dorothy was a motherly lady with a subtle sensuous appeal, beautiful eyes and a quiet way of speaking. She loved the cinema and really controlled us all without seeming to do so. Oscar always remained in the background and emerged from time to time to tell funny stories which made him laugh heartily at every telling. He took care of technical matters and was our “official” photographer. Dorothy was very patient with him, and in turn he was a great support to her. Oscar also loved films, and when CBC Television began, he was the first presenter of a movie series. Dorothy would listen to suggestions, contribute her opinions, nod her head in agreement; but when we next met we found that decisions had often been made by her which never had been discussed but they were usually for the best and made “under pressing moments”. As she didn’t “go out to work” and had no children, she devoted most of her time to the society and in helping others across the country.

Our first showing was Jacques Feyder’s La Kermesse Heroique at the Panda Studio at 321 Church Street, demolished to make way for Ryerson students’ residence and the Rogers Communication Centre. These days, when I walk past that building, on my way to Ryerson and my mind goes back to Saturday, April 28, 1947 at 8:30 p.m. when we began. I see us gathered around a 16mm projector with the screen and loudspeakers, brought in by Oscar–the only technician among us, and our projectionist. The running noise of the machines didn’t bother us nor the break to change reels, but these were drawbacks we would not tolerate once we moved to the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) theatre.

Our first “professional” series in the theatre was on October 15, 1948 and we showed The Blue Angel mentioning in the programme notes (typed by me!) that it was “TheEnglish Version with an ending different from the German version“. We should remember that to bring a group together to show films to the public was an extremely difficult undertaking at a time when non-theatrical exhibition was almost non-existent. Hollywood companies through Famous Players, controlled the exhibition business. The distributors, some still Canadian then with contracts to distribute the films from various studios, could rent us “old 16mm films if they had prints” but don’t dare ask for new and unusual titles, even if they had failed at the box-office. The Rank organization was an exception, and it was not until after TFS showed Hue and Cry to great acclaim that the Christie booked it. Even though we paid rentals, anyone showing films outside the system was looked upon with suspicion–interlopers trying to make money at the distributors’ expense!

We could not have survived but for the National Film Society of Canada (later renamed the Canadian Film Institute) in Ottawa which obtained films for us and the other 26 societies, which later sprung up across Canada, from the British Film Institute (BFI) and the Museum of Modern Art (MMA) in New York, together with prints from the National Film Society’s own collection, slowly building up without the benefit of grants from government sources.

Print availability was difficult enough, but we also had to contend with the Ontario Censor Board and its two dragons at the drawbridge, O.J. Silverthorne and George Belcher, a pair of civil servants who seemed to have been at the Board for ever and knew nothing about film as an art. They would only grant a license for our showings when we became a registered non-profit organisation–admission by membership only to the entire season, with no-one under 18 allowed to join. We were always petrified that a non-member would get in, and the only exception to this was on special occasions when we made seats available for friends and family of existing members. Their invitational tickets had to be picked up beforehand and never at the theatre. In spite of all this (and continuing through the years) our firs ROM season ending on May 30, 1949 was judged to have been more successful. For years to come we were considered to be an eccentric lot (some of us did wear long hair and sandals) who looked down on Hollywood and craved French pictures!

We announced at our first Annual General Meeting that 250 memberships were sold, monies received amounted to $2,025.00 with expenses of $1,369.50 leaving a balance of $655.50 to begin our second season in the autumn. Need I point out that from then until the present, everyone involved in running TFS has done so on a voluntary basis and no grants have ever been received from the city or other government agencies.

During the first season Sergei Eisenstein died. We showed Ivan the Terrible. The members commented that it was “great art“, “disappointingly uncinematic“, “experimental and exciting“, “theatrical and tiring“. A visitor from Galiano Island “passing through” Toronto was pleased to have the opportunity to see Ivan the Terrible and described it as being the “most ambitious lantern slide projection ever attempted“. Cavalcanti’s Film and Reality was hailed and McLaren’s Fiddle De Dee delighted everyone. We noted that “The display of Books in the Lobby was by courtesy of the Rendezvous Book Shop“.

Throughout that first year our program notes conveyed respectful comments and opinions to and from our members. One evaluation received criticised our policy of showing “ancient films” (a reference to the classics) and chided us for our “impatience” over the suggestion that we should show “modern films“, but obtaining these was next to impossible, even if we wanted to. We agreed to “consider the functions of a Film Society” (which I thought we had already done before we started) and members were invited to meet us at Diana Sweets, 188 Bloor Street, for “informal discussions on the subject.” In February 1949 the NFS published a new monthly magazine entitled Canadian Film News, at an annual subscription of $1.00. (A complete set may be read today at the Film Reference Library of the Cinematheque Ontario).

The program notes continued to be informative: the first Canadian Film and Radio Awards ceremony was held in Ottawa and it was “just possible” that Robert Flaherty would preside over the presentation–he didn’t. In a gesture of support to a companion art we announced that the First Canadian Ballet Festival (“the first of its kind to be held anywhere“) would be staged at the Royal Alexandra Theatre and that the NFB “intended to film it“, and the CBC’s distinguished Wednesday Night radio arts program “would record the proceedings“. Though none of the TFS Board ever sought publicity or attention by attaching their names to any programs (that would not have been in good taste) it was discreetly noted now and then that “Gerald Pratley could be heard each Sunday on the CBC’s Dominion Network.” The Board passed a Resolution calling attention to the need for a “A National Film Archive” immediately, and praised the National Film Society of Canada for its “significant contribution to film appreciation in Canada by creating an archive of classic documentary and feature films.”

Members were kept up-to-date with the swift advance of technology with such notes as “Boundary Lines was photographed in Kodachrome and the print we are using is a Kodachrome duplicate. Steel was photographed in 35mm three-strip Technicolor. The print we are seeing is a genuine 16mm Technicolor print with three superimposed dye images, similar to colour rotogravure in process, while the sound track is conventional black-and-white. It might be of interest to members to take note of the rather different effect due to “the colour balances” of the two films. It should be borne in mind that the sound track of Boundary Lines is in colour and hence renders the sound rather differently to that of the silver image track of the Steel film.” Did we know what we were talking about?

In April 1949 we re-introduced members to “experimental cinema” by showing two of Maya Deren’s works, At Land and Choreography for Camera. These were accompanied by Alexander Hammid’s (Deren’s husband) Private Life of a Cat. I don’t think our audience was ready for this. We sternly announced that “members of the executive and the audience will devote three minutes to the consideration of a single aspect of the films.” Few seemed to know what to make of them. They were of course, part of the new colourful and perplexing period of film in New York City with Amos Vogel, Jonas Mekas, and others, all going in many directions in pursuit of film art. We concluded the 1948-49 season on May 30 with Luciano Emmer’s Zero de Conduite (a warning note: “this version is ten minutes shorter than the original“) and Clair’s A Nous la Liberte (note of assurance: “the absence of English sub-titles presents no obstacles whatsoever to the understanding and enjoyment of this action-filled film“) which was compared favourably with the great Chaplin. Chaplin shorts and Grierson NFB documentaries were a mainstay of every season.

The years following continued the pattern of the first. We were at home in the ROM Theatre although we were limited somewhat by a stuffy staff only one of whom, the sympathetic Ella Martin, didn’t really believe that “movies of our kind” should not be at the ROM; and by a small projection booth (enlarged many years later when the theatre was re-designed) with only one 16mm machine, thus making an uninterrupted performance impossible. However, faithful Oscar lugged in the TFS’s own second projector. We continued our Board meetings; there were differences at times over the titles we selected, but the entire period was a valuable training ground for me as reviewer-critic-writer in learning more about the other side of Film–in this case the complicated business of distribution and exhibition. Getting to know how to book films, finding the distributors, how much rental to pay, transporting the movies, dealing with customs’ officials, finding the right people in the business and explaining TFS and what we were doing, and forming lasting relationships with the British Film Institute and the Museum of Modern Art. All this stood me in good stead in the years to come, not only in critical writing, but in programming the Stratford Film Festival, the AGE Film Society and the Ontario Film Theatre at the Science Centre. In most of these endeavours I was greatly assisted by the ever-reliable and capable Patricia Thompson, now the publisher and editor of Film Canada Yearbook which Hye Bossin stated in 1952 under the title of Year Book of the Canadian Motion Picture Industry (Price $2.50). A complete collection is held in the Film Reference Library.

Our meetings took place mostly at Dorothy’s home but from time to time we moved around to the homes of other members, if they were large and near enough. Ruth and Philip Budd had a roomy house at Carlton and Yonge Streets, long since demolished. As for the big exhibitors, we received no support from Famous Players, but Rank’s Odeon circuit was always sympathetic to our cause from Leonard Brockington down through the ranks including Christopher Salmon, Frank Fisher, Larry Brabourne, Charles Mason, Frank Lawson and Bill Moreland. Decent auditoriums with 35mm projection in which to show films were not available for non-theatrical groups such as TFS, and renting a commercial cinema was unheard of–until 1956 when Aldo Maggiorotii (at Warner Bros.) and Elwood Glover (CBC announcer) and myself (all film enthusiasts) formed the AGE Film Society to show silent and early sound films.

As so many of our prints were 35mm we had to find a suitably equipped auditorium. I went to see Christopher Salmon, who was then the General Manager of the J. Arthur Rank Organisation (JARO) in Canada and whom I had come to know and like during my years of broadcasting. I asked him if we could rent the Hyland on Sundays. It was not then a double cinema and had 2,000 seats. It was new and beautifully kept and dignified in atmosphere–unlike today. I explained our situation and he agreed to let us use the Hyland for a rental of $100.00. The reason we asked for Sundays was simple: All cinemas were closed on Sundays in keeping with the Lord’s Day Observance Act. There was some eyebrow raising in the trade and at the Censor Board when we announced our showings at the Hyland, but there was nothing in the law which said that private non-profit subscription membership groups could not show films on Sundays. A friendly policeman appeared at several screenings to make sure that no tickets were being sold–we even invited him in–and these cheerful afternoons had about them a wonderful sense of occasion. And it was pleasant to work with helpful cinema managers in the persons of Barry Carnon, George Spatley and Victor Nowe, who all loved films, were formally dressed and welcomed our members with good humour and cordiality. Everything went so well for AGE that I then went back to Christopher and asked him if Odeon would also rent the Hyland on Sundays to Toronto Film Society (beginning with the 1957-58 season) and the French Cine Club, both hard-pressed to find suitable screens. He agreed and thus the Hyland Cinema became the home for film society members until 1961 when the laws were modified. Toronto was “opening up” and cinemas could take advantage of the changing times. But for the TFS, this meant the beginning of an almost continuous search through the years to come for a proper venue in which to show its programmes–now in four different series each year.

Returning to our early TFS showings, we began on October 17, 1949 at the ROM not as the Toronto Film Society Study Group, a name not to be used again, but as The National Film Society – Toronto Branch. We had gone through a great deal of prolonged negotiations carried out by our legal expert, Roy Clifton, who announced the TFSG’s change of name from the stage before the showing of Duvivier’s Un Carnet de Bal. The National Film Society – Ottawa was, of course, the original name of the Canadian Film Institute and in 1939 other individuals had formed a Toronto Branch, but which, we had reason to believe, never started because of the outbreak of WWII. But legally changing the affiliation from them to us took a great deal of time and money. A search of Helen Arthur’s comprehensive TFS Library and Archives failed to unearth more details. I remember opening night with Un Carnet de Bal was not the auspicious occasion we had planned and looked forward to: A member, one of several, summed it up in his letter. “A worn print badly spliced, subjected to brutal Québec censorship, lacking English sub-titles, it looked like an exhibition of sleep-walking.” Oh, the agonies we suffered finding and booking prints we could not screen in advance, to make sure they were decent, and then finding they were not when the projection began! We felt like going into hiding when the show was over. But this is a condition which stays forever with those of us involved in specialised cinema.

With this fresh if somewhat disappointing new beginning as the NFS-Toronto Branch, we added colourful covers to our programme notes–which usually ran from three to five pages. In this pre-Xerox era we had to have them “run off” at outside print shops. Our notes always ended with the notation GOD SAVE THE KING referring to the closing after each performance with the national anthem as it was then. All theatres and cinemas closed with the playing of–or a film of–the national anthem. We showed an excellent compilation of shots of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth set against the Canadian backgrounds made by Crawley Films; taking the plunge we decided to buy a print instead of renting it–cost $10.00. I wonder what became of it!

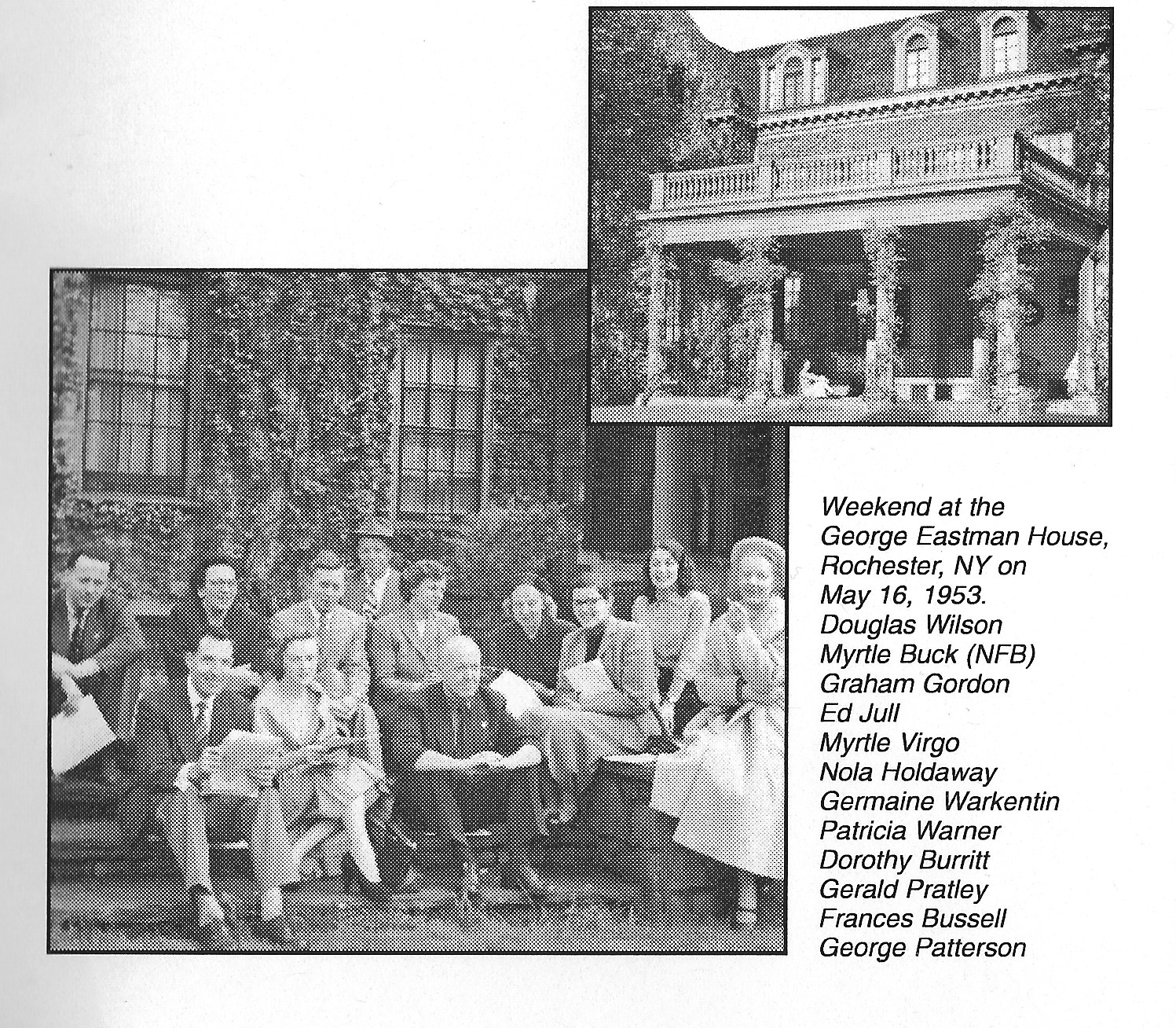

This was time for visitors. We had no money for travel, hotel, or meals and until well into the sixties when our membership was large enough to afford the likes of James Card and Louise Brooks from the George Eastman House in Rochester–where we began to spend our Labour Day weekends watching silent and sound classics from the marvelous Archive collection housed there and shown to us at the Dryden Theatre. We all piled into Ed Jull’s van and drove down in high good humour. On many occasions I took the rive with Clyde Gilmour (who always wrote a column about the TFS programme in the Telegram and later the Star at the start of every new series). Clyde could never find his way on his own so I became the navigator. We all stayed at the Treadway Inn on East Avenue, with its silhouette sign of a Dickens-like character, within walking distance of the George Eastman House. Joan Fox remembers a party we were at with the quiet spoken Thorold Dickinson, so noisy we could barely hear what he had to say! Returning to our visitors however; in these early years Maya Daren caused a sensation. She came with her latest film, Meshes of the Afternoon. Most of us didn’t understand it–or her, although several of our group professed to do so! She hitchhiked her way to Toronto and stayed with friends of a similar taste in clothes, smokes and make-up. We provided meals and drinks–more o the latter than the former! She excited almost everybody with her lively behaviour and outspoken manner. At Dorothy’s reception for her she sang, danced, played some kind of tambourine, drank and smoked copiously and ate very little! This was certainly the first ‘wild party‘ in the history of TFS; whether there were many others I’m not sure. At the opposite extreme was Roger Manvell, historian and critic from London who came through the courtesy of British Council. His Penguin paperback, simply titled film was the first serious consideration of cinema to be published in English and inspired me to begin my life in film. Imagine: as there were no films made then about the history of film, we had shown, with a sense of pride, Roger Manvell’s series of BFI filmstrips (what were they you may well ask) dealing with the history of the silent and sound periods, each one being devoted to a different country. Manvell was learned and distinguished and our discussion from the stage after showing Lubitsch’s Trouble in Paradise was one of my earliest appearances as a moderator and I need hardly say that I was extremely nervous. But all went well and I remember an attractive student from the University of Toronto coming up to the stage and congratulating Manvell for his talk and myself for my radio programmes. Her name was Pearl Sheffy. She left for Europe the next week returning almost forty years later as Pearl Sheffy-Geffen, a writer of considerable talent about stage and screen celebrities. The number of our members who became prominent in film in later life is impressive and pleasing. Later guests were Frances Flaherty, Pare Lorentz, Ernest Reid and Gilbert Seldes.

We always showed up to three or four short subjects before each main film. Our programme notes would carry notices such as Doors will close at 8:15 sharp and open at the end of the first film for latecomers to be admitted and seated. No smoking please. The lobby film was shown between 7:45 to 8:10 p.m. A typical item might be One reel silent in colour of scenic shots of Banff filmed in 1946 by Dr. A.D. Pollock of Owen Sound. And again “Three silent ‘experimental’ films, Fernand Leger’s Ballet Mecanique, Joris Iven’s Rain and Douglas Crockwill’s Long Bodies, will be accompanied by musical scores from phonograph records.” These were arranged by the knowledgeable Fraser MacDonald who had since joined us, also from CBC Continuity, but as I said earlier, we never took published credits for our contributions to the society other than as members of the Board at Annual General Meetings. Oscar brought in and set up the gramophone, plugged into the projector’s speakers, so simple today, so difficult then. We formed a Members’ Participation Committee; in other words, we needed help!

When we showed Drug Addict (1948), a sensational film for its time, by Robert Anderson for the National Film Board, we noted our indebtedness to The Department of National Health and Welfare for permission to show this restricted film. Restricted did not refer to the Censor Board classification which had not yet been introduced, or even thought of, at that time, but to the Department’s restriction of such a “dark subject” as being dangerous for “ordinary audiences”. Again, with the short subject Rodin we assured members that “in order not to spoil the effects of the photography of the statues the film is free from super-imposed subtitles. It can be understood without them, but for those who understand French the commentary is valuable.” After the showing of Intolerance which held most members in thrall, one wrote to say “the misplaced laughter on the part of some members was deeply resented.“Yes, we had our disappointing individuals: Why were they members? Again, In the Auditorium from 7:55 to 8:09 pm a Talk by Robert J. Flaherty on disc courtesy of the BBC. We are proud to present to members the opportunity to hear the voice of the famed documentary director describing in his own words some of his vivid experiences as an explorer-filmmaker. To ensure audibility for early-comers, the doors will be closed for the duration of the recording; members not arriving for the talk may be interested in viewing the display in the lobby of educational film books.” We made weightly decisions in those days! The film shown was Moana.

All Chaplin and McLaren shorts were much praised and appreciated. The Waverley Steps by John Eldridge was “a fine documentary“, “it is not a good documentary“. The People Between (by Grant McLean for the NFB 1949) a controversial film McLean shot entirely in China was warmly praised by Basil Wright, himself a distinguished documentary filmmaker who came to speak to us and said, in part, “Not only is the Canadian public vividly and dramatically informed about the basic problems of China, but also the world at large may benefit from the same film; and that, by the way, is very good propaganda for Canada, let alone China.”

During the end of the 1950 series we were plagued by sound problems which the ROM seemed unable to rectify. We heard from our members, naturally, and one wrote: “The reproduction of sound is deplorable. How much longer is this to continue?” We replied in our notes: “This is not the fault of the films. Unfortunately the position of the new loudspeaker recently installed is not satisfactory. Members’ complaints have been brought to the attention of the Museum and it is hoped that the original high quality sound will return for our last Exhibition of the Season.” And: “Members wishing to rejoin next Season are urged to return the advance application form requesting membership in the Society’s 1950-61 Season. These may either be mailed to 233 Grendadier Road or left in the Reservation Box in the lobby.“

Always concerned about Canadian films, or the lack of them, we urged members to read “An article on Canada’s feature film production compared with the production in other lands” being circulated to members for their information. “This Society is most concerned that Canada is the only country of its size in the world that does not have an industry producing feature films about and for its people.” Sounds all too familiar!

By October 1950 when our Third Season began at the ROM we were now Toronto Film Society (officially registered as a non-profit group) and the National Film Society in Ottawa had changed its name to the Canadian Film Institute in keeping with the change of name of the National Film Society of Great Britain to the British Film Institute. We then became a Member of the CFI paying dues, as did film societies across the country, to support it financially (again, there were no government grants in those years) and to build up its library and archive of prints for distribution to the societies at very low rentals. It’s interesting to look back and see that we obtained our short films (we often had up to five on each programme) and many of our full-length feature films, from four main sources: the CFI, the MMA, the NFB and the J. Arthur Rank Organisation 16mm film library. Later, in the sixties, film societies in this country became members of the Canadian Federation of Film Societies (CFFS), a division of the CFI, and from this position of strength and solidarity we were in a position to book specialised films (then called by the misnomer, art films from the commercial distributors–who were not slow in realising that, small though the returns might be in comparison to those from commercial cinemas, rentals from film society showings were far from being insignificant. In Britain and the U.S., film societies proliferated and became an important source of revenue for the main American distributors whose libraries contained films, many of them new, which had ‘failed at the box office‘, were never shown outside the main cities, and were the kind of films the societies believed in showing and supporting. The Hollywood studios, at first opposed to any showings of films not controlled by them at film societies and festivals, slowly came to recognise the value of our work around the world, in the Commonwealth countries in particular, and that of the cine-clubs which sprang up throughout Europe. But, back to our third season, we noted with regret that the J. Arthur Rank Organisation had closed down the Children’s Entertainment Film group and its director, the distinguished educator Mary Field, had left to become a member of the British Board of Film Censors. Rank made 193 full-length films for children since 1944, all produced by Miss Field. In 1950 she won three first prizes at the Venice Film Festival.

With the showing during this season fo films by Maya Deren we plunged our audiences into the world of experimental film with a vengeance, informing them sternly that “Maya Deren is concerned above all with film as a creative, independent art form, quite distinct from the entertainment, documentary and educational functions which film had to a measure fulfilled. She has attempted to create experiences on the film out of the very nature of the film instrument–that is–its temporal and special and spacial resources. It is the effort of the individual to relate himself to a fluid, apparently incoherent, universe.” That gave them something to think about and later we urged members to join us at the first Joint Discussion Group in the Women’s Union Theatre on the University campus. As the moderator I felt more like a referee as praise and denunciation filled the air–much of it very hot! At our next showing in December it was a pleasant relief to play Santa Clause and hand out programme notes from my sack. This holiday evening was devoted to comedy and music beginning with Chantons Noel, a one-reel collage in Kodachrome made at the NFB by James McKay–a winner in the first Canadian Film Awards; a cartoon from Warner Bros., Inki and the Minah Bird (1943) “the first of a new school of cartoons” and, several additional shorts later, Harold Lloyd’s High and Dizzy and Keaton’s The Navigator both with musical accompaniment by the lively and colourful organist, Ruby Ramsay Rouse, at the ROM’s somewhat out-of-tune piano. Notice–“Found: a dark grey spherical button. Apply at the check room.“

Throughout the seasons we were always anxious to draw the attention of our members to films we considered worthy of our support showing at what few specialised cinemas had opened since we began: “Faust and the Devil at the Towne Cinema following the re-issue of City Lights: The affaire Blum revived at Bob and Lionel Lester’s King Cinema at College and Manning.” This was formerly The Kino devoted to showing of Russian films and managed by Leo Clavir. But with the start of the Cold War and Russia becoming a despised nation, the showing of new films and the classics from the USSR came to a stop. With The Kino being associated with everything “communist” the name of the cinema had to be changed. The Lesters, having no money to spare, changed the last letter to “G‘, thus becoming the perfectly respectable King Theatre. In commercial cinemas (to show how broadminded we were) we recommended Elia Kazan’s Panic in the Streets, John Huston’s “not to be missed” Asphalt Jungle, “the best of current American production“; and John Ford’s “grand and invigorating western” Wagon Master. We were also pleased to show many of the excellent documentaries then being made by the progressive Shell Film Unit in Britain, one being A Tall Order,” a film of great clarity and refreshing sequences showing the making of a fractionating column and its subsequent shipment from the UK to Venezuela.” I wonder if it’s still there, working efficiently one trusts! Later it took almost an entire page in the programme notes to come to terms with Claude Jutra’s Movement Perpetuel, his first film and winner of the Amateur Class in the newly established Canadian Film Awards.

Letter from a member: “I read my copy of the Members’ Evaluations and Talking Back to the Members with avidity. But I take belligerent exception to the suggestion ‘Please do away with announcements from the stage’ which are always of importance to the audience and to our advantage. It is so much warmer for the announcer to appear in our midst. There is a satisfaction in being able to see a member of the board of directors to whom we are indebted. Whoever made that suggestion must be more at home in the commercial theatre.“

One of several brickbats: “Chantons Noel replelled me. The life of Christ and the worship of God are sacred, not subjects for experimentation along the lines of comic strips and Mickey Mouse.“

On the other hand there was nothing but a chorus of praise for Night Mail (1936), the Basil Wright/John Grierson/Harry Watt/Cavalcanti/Benjamin Britten/W.H. Auden “landmark film which has influenced almost all film-making since its inception and even today remains one of the truly great documentaries of our time.” We were also caring about members who for some reason or other found some of our programmes too long (three hours was not unusual) and so “at the conclusion of the main film, house lights will go up so that those who want to leave early may do so.” Then we would show another long short subject! This brought us a sarcastic letter: “The programming hit a new low. Imagine having to sit through 64 minutes of shorts–almost all dispensable–and then a 7-reel full-length film at silent speed! A few more programmes like that and I can see that the artsy-crafty cliquey set running the film society will have the organisation all to itself and then be free to run any number of shorts it wants and perhaps even two full length films in one evening!” At our next showing, which happened to be Greed, there were no shorts, but Stirling Campbell opened the evening on stage by reminiscing about his years in Hollywood working for von Stroheim!

Then came our showing of A Special Programme for Members and their friends, which we, the directors of the board, decided upon after much discussion at Dorothy and Oscar’s home, the purpose being to “raise funds to increase the amount the Society will be able to contribute this Season to the Canadian Film Institute.” But, “as the Society is not permitted to make a charge for this Programme, donations may be accepted, the amount of any donation to be decided by the individual. A 75 cent donation is, however, mentioned as an indication of the Society’s objective.” I think we had a successful evening, again at the ROM, but I don’t remember how much we raised. Under what might be called Helpful Hints, we replied to “Enquiries re Tinting in Greed” with the following: “The yellow colour on the screen of the symbolic “gold” shots was achieved by inserting a “filter” into the light beam of the projector at the appropriate times. After some experimenting, a 5 x 7 frame was used to hold a piece of theatrical “straw gelatine”; this was placed about 2 ft in front of the projection lens. Bruce Young, a member of our House Committee, cued in the gold filter just as records are cued in for music scores. When Greed was first made, the prints had the necessary section printed on positive stock of the correct colour. Such small details as gold teeth, gold bars of the cage, etc. were coloured by hand as 35mm film was slid along a long work table while an assembly line of girls painted various details.“

“Notice: The Annual General Meeting will be held at Wakunbda House.” Where was that?

Forever contemporary and Cheers for the Empire: The NFB’s Look to the Forest (directed by Donald Fraser with Special Forest Consultant, Major General Howard Kennedy) was described in our notes as “This powerful film, set against the dense forests and barren wastes, where forests once stood in B.C., was designed to emphasize the vital need to halt careless exploitation…the director just misses producing a masterpiece.” A film from the other side of the world, Daybreak in Udi (directed by Terry Bishop, UK 1949) was described as being “A re-enaction of a project undertaken by native Nigerians. The film shows how some of the more enlightened people of Umana build a maternity home with local voluntary labour and overcame by themselves, opposition headed by an influential reactionary called Eze. The film’s release was timed to coincide with the officially sponsored Colonial month organised to develop the interest of the British public in their colonial responsibilities. The U.S.A. gave it an Academy Award in 1950.“

Our 1951-52 season started badly with the ROM letting us down with its projectors. After opening with Renoir’s La Regle due Jeu (The Rules of the Game), our notes for the following programme began with this statement: RE SOUND QUALITY AND PROJECTION OF FILMS–All films are tested for clarity of sound and for picture before every Exhibition Meeting. Warning has always been given in the programme notes on the few past occasions when it has been necessary to accept a faulty print rather than miss the chance to see an important film. The distorted sound and difficult-to-read subtitles at the first meeting of the season were most unfortunate but not the fault of the prints used. The Museum has since had its projectors corrected. It should be made clear also that the projectors are NOT operated by Members of the Society but by professional projectionists. Members are invited to send in suggestions and comments about projection and are assured that they will be passed on fort he guidance of those concerned.” About Rene Clair’s Le Million we quoted Grierson, who said “The story is a delightful trifle, a mixture of satire, slapstick and fantasy. In lesser hands Le Million would have been a comedy. In Clair’s it has become a fairy tale. There is magic in it.” The MMA wrote: “The use of sound in counterpoint rather than in supplement to the images was revolutionary in 1930, and its full implications have yet to be acted on by today’s craftsmen. A truly international sound film it dispenses with over-printed English subtitles because none are needed to clarify its story.“

Current films meeting with our approval were Seven Days to Noon (Roy and John Boulting) “as close to being the most perfect movie you’re likely to see in some time“, A Place in the Sun (George Stevens) “A skilled and moving attempt to film Dreiser’s tragedy“; The Big Carnival (BillyWilder) “a bitter, sardonic examination of American sensationalism“; Teresa (Fred Zinneman) “searching, compassionate movie about contemporary humanity’s problems“; Chance of a Lifetime (Bernard Miles) “an agreeable modest but enterprising story of workers who take over a factory and find out how difficult it is to run a business.” How times change: we showed an impressive documentary from Great Britain called The Undefeated by Paul Dixon, “an intelligent and extremely competent film designed both to show the achievements of the Ministry of Pensions and the problems of the disabled.” Roger Manvell described it as the best film shown at the Edinburgh Film Festival that year.

“ANNOUNCEMENTS: Applications for membership in the Society and programme plans for the next Season are being mailed to all members. To be sure of Membership in the Society, members are urged to pay the dues now or reserve memberships. Fees remain at $10.00 double, $6.00 single, $3.00 students (50 only available) for Nine Exhibition Meetings.” Screenings or projections were terms not then used. We were a “Society of Members who attended Exhibition Meetings.” The fact that our purpose was to show films was never made to appear as being our major objective. This was always considered by the Establishment to be a commercial undertaking. “Art” as someone once said, “had nothing to do with it!” A note accompanied the showing of Cocteau’s The Eternal Return: “It is unfortunate, but we think not catastrophic, that in the print of this film, the only one available to us (due to inexplicable actions variously attributed to the New York Censor Board, the Legion of Decency, and the Quebec Censor Board) some of the earlier love scenes have been shortened, and the end of the film, in which Nathalie dies beside Patrice’s body, has been eliminated.” What with bad prints, censor boards, faulty projectors, poor sound, it was enough to send one home with a headache! But–Ruby Ramsay Rouse’s piano accompaniment to The General evoked cries of “Hurrah, Hurrah“, “Bravo“, “Wonderful“, “A Large Orchid“, “Just the Right Touch“, “Special Thanks” and “The music seemed to add words to the picture.” At times like this we felt much better. Ruby, like her contemporary Horace Lapp, actually played in cinemas when films were silent. In regular cinemas we recommended three Italian dramas, Without Pity, The Girl From the Marshes and Angelo. “A real celebrated Italian film, To Live in Peace, which Toronto has been waiting to see for years, has finally been booked into the International Cinema” (Yonge at Manor Road) to follow the “inexplicable and seemingly interminable run of Laughter in Paradise.” (This comment revealed our somewhat snobbish side. Did it never occur to us or anyone else that Laughter in Paradise was still being shown because people were going to see it?) We also took issue with the Uptown because it had been advertising Mark Robson’s Bright Victory “a moving account of a blind veteran’s readjustment to life“, for months but was continually “putting it off in favour of routine releases.” Later comment: To Live in Peace ran for only eight days at the International prompting us to say, “Let’s face it, you and others who didn’t go to see it are one of the reasons why foreign films fail so disastrously and quickly at this house!“

However, we were delighted to receive unexpectedly from the National Film Board’s Library in Ottawa the 10-minute Loony Tom, in which the California poet, James Broughton, “devotes himself to the sprightly cause of spreading joy throughout the world,” and F.R. Crawley’s Newfoundland Scene was described as “Canada’s finest achievement in the documentary field to date.” We ended our fourth season with a tribute programme to the artist and poet Humphrey Jennings and showed Words for Battle, Listen to Britain and I was a Fireman. We opened our notes with these lines:

I see London

I see the Dome of Saint Paul’s

like the forehead of Darwin

I see London stretching away North and North-East along dockside roads

and balloon-haunted allotments

Where the black plumes of the horses precede

and the whole helmets of rescue-squad follow…

I see the green leaves of Lincolnshire carried through London on the

wrecked body of an aircraft

As well as the art and history of film, we were it seems, now looking back, always determined to tell our members more about techniques than they might have wanted to know. After showing films whose method of presenting their stories was not in the direct manner, they heard a discussion o why and how it was done. Some members didn’t want to know, but most did, as with the talk following Cocteau’s Orphee, “a wonderful idea to follow a most intriguing film.” I cannot remember who all the speakers were but Oscar Burritt liked to talk about his and we frequently asked local filmmakers and film enthusiasts to take part. George Patterson, a film devotee of the highest order (he never missed a single film opening in Toronto) began to write Current Film Notes as part of our programme notes–the length of which we had to frequently curtail due to the high cost of printing them. In October 1952 his long list of comments included William Wyler’s Carrie “A film of considerable merit and poignance…the period atmosphere is splendidly evoked and the acting of Laurence Olivier and Jennifer Jones is simply splendid.” On looking back over the many short films we included in our programmes one is struck by how great were the artists who made them, including Arne Sucksdorf, Joris Ivens, Henri Storck, Basil Wright, Norman McLaren, Cavalcanti, and so many others. So much of what we see today under the description of documentary is but a pale shadow of what is past with no-one achieving the greatness of those who made them. In Critic and Film, a series designed by the British Film Institute to experiment in furthering film appreciation in film societies, we showed No. 3, Odd Man Out, in which Basil Wright analyses the dramatic construction of Carol Reed’s film with reference to editing, camerawork and sound effects.

Toward the end of 1952 we received the following letter from the Secretary of the Irish Film Society of Dublin which makes interesting reading today:

“Yours is our first communication from Canada; glad you are operating so successfully. We have shown most of the films on your list including all the Norman McLarens available. Fiddle Dee Dee is a great favourite and we have shown it again and again. You are very fortunate to have McLaren so close at hand. We have not seen Newfoundland Scene and the other Canadian films you suggest; we will certainly contact the Canadian Embassy about them. It is difficult to answer your question regarding The Quiet Man. I like Ford and found the film most enjoyable. I was actually there when it was being shot. It is, of course, a glorious farce and so outrageously ‘stage Irish’ as to be recognizable as such. It was a great box-office success here; the audiences rocked with laughter except the self-conscious nationals who feared the outside world would take it seriously. A company has since been formed here and Ford is coming back to make another film. As you probably know we have no film industry here, producing only a few documentaries each year. The Government is now considering a plan for a film industry that I have placed before them. It is surprising you are not producing feature films in Canada. Surely after your experience in documentary, you could compete even to a small extent with Hollywood. Apart from artistic and patriotic considerations, it would have great international and economic advantages.” The Secretary goes on to discuss No Resting Place, a feature made in Ireland by Paul Rotha. He did not like it and felt that “Rotha lacked experience in scenes involving synchronized dialogue. Cutting was slow and awkward and characterization sightly phoney. As an admirer of his documentaries I respect and hope Rotha will become more accustomed to dialogue in time. I must add that his picture of wandering, impoverished, quarrelsome ‘tinkers’ is quite accurate. They are a source of great worry to the farmers and others who happen to be close to their temporary resting places.” An earlier statement pointed out that “the story has no basis in fact from our point of view and was most unreal.” Mr. Patterson, your Current Film Editor, who must admit to not having been in Ireland, cannot refrain from adding that he saw No Resting Place in New York, found it most moving and seemingly quite realistic, certainly more so than The Quiet Man, and thought the acting of Eithne Dunne of the Abbey Theatre quite unforgettable. We received a copy of the Irish Society’s Annual Report which gives a comprehensive and absorbing account of their activities. We are placing it on the Bulletin Board at the Exhibition Meeting on November 10th.

We also took up two entire pages telling members how we went about experimenting with sub-titles on filmstrips to accompany foreign films which came to us without sub-titles. I cannot believe we did it, looking back on such a complicated procedure.

By January of 1953 God Save the King was now God Save the Queen and as part of our shorts programme of the Fifth Meeting we screened the NFB’s stereoscopic interpretation of Canada’s national song, O Canada, drawn by Evelyn Lambert. We apparently liked it better than the Left Eye Version and decided to purchase it as a companion piece to God Save the Queen. We were “grateful to Guy Glover of the NFB for allowing us to show Douglas Wilkinson’s Land of the Long Day before its general release. Following in Flaherty’s footsteps Mr. Wilkinson spent eighteen months in the North and returned with enough footage to complete three films.” We also used up a page to write a few notes, after Paul Rotha in The Film Till Now, entitled The Expressive Capabilites of the Camera. Later, the comments came in about O Canada. Most applauded; but one said: “I resent very much this standing to “O Canada routine”; another, “To have the Canadian anthem is a laudable aim but must we have it in the abstract? What a dull, unimaginative work. Give us the Queen any day. She’s far more glamorous.” I may not have mentioned that we always played classical music before the evening began and during the intermission. A work by Raymond Scott was described as “utterly horrible“.

After showing A.E. Dupont’s Variety (which, like Pabst’s The Love of Jeanne Ney, is seldom seen these days) we held a fascinating discussion in Falconer Hall with Gilbert Seldes. “Three scenes were re-screened to illustrate how brilliant camera work and direction can portray character studies and create group atmosphere by means of thumbnail sketches.” The opinions expressed were thoughtful and introspective, and the effect of the film and its interpretations on the audience was gratifying. Our more formal discussion meetings with members began in 1958 the first film being I Vitelloni.

For the final showing of our Fifth Season we moved to the Towne Cinema on Bloor Street (now demolished like the International) on Sunday, April 12, 1953. We left the ROM that night because our films, all by Robert Flaherty, on that evening were 35mm. Certainly this was our first time in a commercial, albeit also in art house cinema, programmed by Yvonne Taylor, the wife of distributor and exhibitor, N.A. (Nat) Taylor, but it was a pleasant change from the often stony darkness of the ROM.

During these early seasons the Society attracted thousands of film enthusiasts, and others, who, while not following films quite so avidly, wanted to see the thoughtful and lasting side of filmmaking from around the world–films which opened new vistas, new societies and imaginative interpretations of human endeavour with its sorrows and triumphs. Considering the difficulties of the time I think we did exceptionally well, and there were many other knowledgeable individuals apart from Board members previously mentioned, who gave their time and enthusiastic support to keep us going; amongst those who come to mind are Frances Bussell, Gerry Morses, Douglas Wilson, Ed Jull, Helen Cowan, Myrtle Virgo, Beatrice Trainor, Diana Southwood, Eugenia and Peter Webb, Myrtle Buck, Culry Posen, Germaine Warkentin, Ted Hall and Bryan Barney. Amond our members were bright and enquiring individuals who later made their names in critical writing, including Joan Fox, Wendy Michener, Doris Mosdell, Nathan and Gloria Cohen, and so many others; while many more including Joyce Weiland (“I was inspired to make films by what I saw at the TFS“) and Christopher Chapman, Graham Ferguson, Imax, Don Shebib, became filmmakers. And the invaluable Douglas Wilson, who created and maintained the TFS Film Archive, as throughout the years, a faithful member. However, he spent so much time talking on the telephone with us we sometimes wished the instrument had never been invented!

With the start of Season Six in September 1953 we were back at the ROM. At the Annual General Meeting, some weeks previously, I chose not to stand for re-election to the Board. I felt that five years was enough. My broadcast work at the CBC together with many other film activities limited the time I had to give to TFS. I also felt that the many newcomers joining us should have an opportunity to bring fresh approaches and new ideas to the programming and running of the Society. In the years to come new arrivals rejuvenated activities, among them Patricia Thompson, Clive Denton, Jaan Salk, Bruce Martin, Frances Eastman, Donald Swoger, Peter Poles, Barry Chapman, Warren Collins, Arne Ljungstrom, Frances Blau, Helen Arthurs, Laurence Dabin, Bill Sturrup, Don Sangster, Juliette Wheten, Erju Ackman, Harry Purvis and so many others. In Ottawa at the CFI we worked with Charles Topshee, Chris Wilson, Gordon Noble and Peter Morris and out West with Marshall Gillilaud, Talbot Johnson, Dick and Aneke Shoemaker, Ed Abramson, Stanley Fox–to name a few.

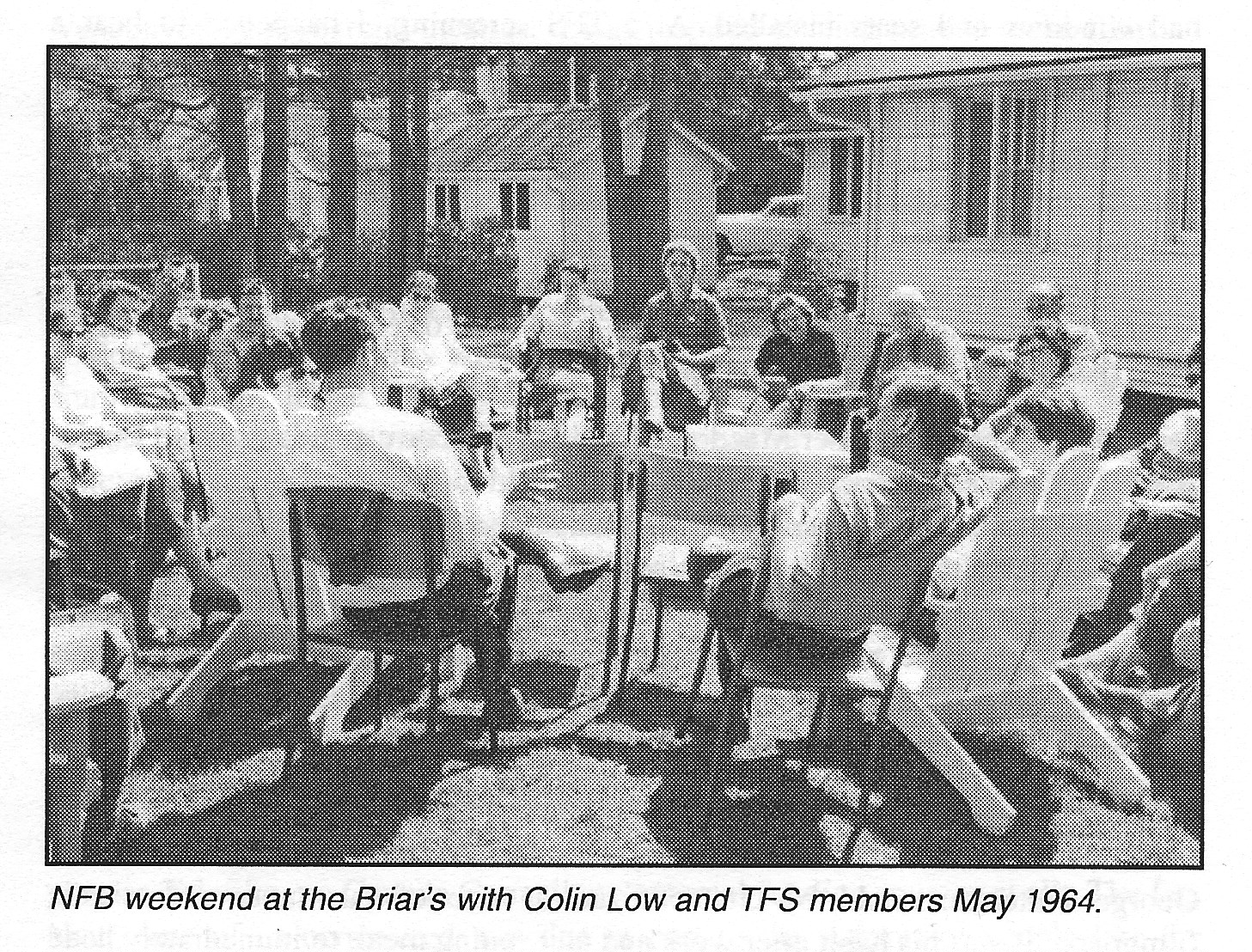

In the years that followed the Fifties, Toronto Film Society doubled and tripled its membership and its programmes became four each season. Visits by filmmakers and historians such as Stanley Kramer, William K. Everson, Aldo Maggiorotti and Elwy Yost became more frequent. They brought with them prints we might not have obtained without their assistance. The annual retreat at The Briars Inn in May, (now held at Kempenfelt Bay) became famous for the meeting of members lost in the enjoyment of wonderful old films, many that never made history. Many members such as the Feldman family–Dolores, Morris and later Caren and Ronda, have been going to this weekend since it began in 1955. There were scandals too, such as the weekend when one lady member ran away with another member’s husband!

As for George Patterson, he was truly our most filmminded individual. Born in Winnipeg in 1909 he moved to Toronto in 1947. He was one of our founding incorporators and he served as a Board Director for 25 years, stepping down in 1973, the year in which he later died. He wrote 25% of TFS Program Notes over a 26-year period and his life was devoted to Film–he saw every new release and never missed a TFS showing.

As the years passed the Society varied its screenings between international films, the classics, silent movies, and entertaining “B” pictures. Prints and censorship became problems of the past. I look back over the 50 years of the Society and marvel over what it has achieved and how it all happened and what wonderful times we had. In 1951 I took on additional responsibilities by accepting the Chairmanship of the Toronto and District Film Council–the organisation started by John Grierson during the war years to bring NFB films to the people. It outlived its usefulness in the late Sixties. With the approach of the millenium, the same fate seems likely to befall film societies. Happy anniversary TFS.

************************************

The Beginnings of TFS

by Ben Viccari

……………………………………………………………………………………

I came to Toronto in late 1947 from London, downsized from a career in the film industry by the Attlee government’s emasculation of the Rank Organization. Looking back fifty years, I can describe the Queen City in four words: Belfast on the Don. I supposed I stayed only because, within three weeks, I found a job more or less compatible with my abilities and was able to live in relative comfort.

The city’s artistic life was circumscribed by such comfortably safe ventures as the Toronto Symphony and Mendelssohn Choir; the Toronto Art Gallery; the ROM; occasional visits of worthwhile plays and entertainers to the Royal Alexandra Theatre and the Eaton Auditorium; the Earle Grey Shakespearean company; the Dora Mavor Moore Players and Yvonne Taylor’s International Cinema which, to her credit did book British and sub-titled European films at every opportunity. With the exception of the CBC–regarded by the city’s strong conservative element as highly subversive–little artistic risk was taken in Toronto, as in the rest of Canada with exception of Vancouver and Montreal.

In the summer of 1948 I discovered the Toronto Film Study Group, which occasionally rented 16mm copies of worthwhile films and discussed them after the showings. I attended one of these to see The Oxbow Incident and met the driving forces behind the group: the late Oscar and Dorothy Burritt, who had come from Vancouver due to Oscar’s posting to the CBC in Toronto. During the discussion, I learned that the Burritts together the late Julia Christensen, editor of the now defunct Magazine Digest, Harold and Tina Smith, students at the University of Toronto, musicians Philip and Ruth Budd and Gerald Pratley, were planning to develop a film appreciation society on a larger scale. Because of my background in the British film industry I was asked to join.

Other members of our group were Moira Armour, Maureen Balfe and Roy Clifton, teacher at the Crescent School and law graduate. Roy’s presence was invaluable, since on applying to incorporate Toronto Film Society, we learned from provincial authorities that such a society had been incorporated before the war but although it had ceased to function the charter was still active. With his legal expertise, Roy was able to contact the surviving directors of the former society and persuade them to relinquish the charter to an interim board of directors.

We booked the Royal Ontario Museum Theatre for a season of showings from the fall of 1948 to the spring of 1949, six I believe in all, set a subscription rate and developed a brochure which staunchly proclaimed “Film is an Art”. We developed lists of friends and known cinema lovers, and whenever possible used the mailing lists of other organizations. I remember going to see Dora Mavor Moore and humbly asking for the use of her list. With a generous gesture she said, “Yes, indeed. After all, we’re all travelling the same road, aren’t we?” Little did she know she would live to see so much professional theatre in Canada and have annual awards given in her name.

Good films were available on a rental basis from New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) and we booked a double bill of the Dietrich classic The Blue Angel and John Steinbeck’s The Forgotten Village. We addressed the envelopes, licked stamps, pleaded with editors to run notices about the formation of the society and by the time we opened in October 1948, had a nucleus of paid-up members, with subscriptions available at the door.

On the morning of the opening we still hadn’t received the two films from MOMA, and a frantic search revealed they were being held at customs and nobody had notified us. They were retrieved and rushed by cab to the projection room only minutes before the doors were opened. The audience’s reception was overwhelming and we signed up enough members that evening to guarantee a season of six showings. By the end of the year we had duly elected board of directors with Gerald Pratley as our first president. His air of quiet authority brought balance to a widely diverse group.

One of our directors was Stirling Campbell, a First World War US flyer who, in Hollywood, had achieved fame as a director of flying sequences. His scenes of combat in the original Dawn Patrol were so good that they were retained for the second and better version of the film starring Errol Flynn, David Niven and Basil Rathbone. Campbell had come to Canada to direct flying sequences for Bush Pilot, starring Austin Willis, Jack LaRue and Rochelle Hudson, arguably the worst film ever produced in Canada.

While one couldn’t accuse Stirling of supporting the notorious House Committee on Un-American Activities which persecuted the Hollywood Ten, he was a true product of Hollywood and couldn’t seem to get it into his head that there was an audience in North America for European classics like Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin. We showed it in the first season, set to a magnificent taped score of Russian music assembled by Oscar Burritt. At every board meeting Stirling would come up with gems like this, spoken in his New York accent, “Why do we have to show all those Russians mugging into the camera when we can show Canadian films like Bush Pilot?“

During the summer of 1949 we were busy programming for the next season when we were informed peremptorily by the Royal Ontario Museum management that the theatre would be unavailable to us. Some discreet enquiries revealed that the RCMP had been investigating us–presumable because the showing of historic films from behind the Iron Curtain were considered subversive. It took the threat of a lawsuit to make the Museum board change its mind, and we stayed at the theatre there without further harassment for many seasons.

We were also responsible during the 1949-50 season for hosting a showing of Hans Richter’s Dreams that Money Can Buy as an “extra”. This famous expatriate Dadaist painter had assembled a surrealist film in six episodes, each inspired by works of such avant-garde artists as Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Man Ray, Fernand Leger and Richter himself. The three performances were near sell-outs; Richter, a delightful old man with a mischievous sense of humour, attended all three and introduced his film. We were able to supplement the film with a small exhibition of Ernst’s works in the Museum Theatre lobby. I remember Hans’ pleasure at a headline in the Globe and Mail which proclaimed that Duchamp’s famous abstract Nude Descending a Staircase was one of the episodes. Of course, the treatment had as little to do with figurative nudity as did Duchamp’s original painting. But Richter, the eternal prankster of art, loved the headline and the publicity it gave us.

After a couple of years I dropped off the board but was delighted that Gerald Pratley remained for so long and left his stamp on TFS, as he has done on so many programs and institutions that have advanced the cause of Cinema in Canada.

************************************

The Burritt Influence

by Douglas Davidson

……………………………………………………………………………………

This piece might have been written by any number of young film lovers whose lives were influenced by Dorothy and Oscar Burritt although the personal impressions are, of course, my own.

I was one of those people who, from the time I was maybe 11, was seriously interested in film–a film buff. But I felt reasonably unusual in this until I got to the University of Toronto in the fall of 1948. Some time during that year–I think it was cold–there was a notice in the University newspaper, The Varsity, announcing the time and place of a meeting for people who were interested in film. The person we met there was Dorothy Burritt, who proceeded to give us a pitch on the glory of film societies, and encouraged us to start one at U of T. I’m not sure who else was there that night, but I do have pictures of some of the executives of the U of T Film Society when it was rolling including Roy Little (who now lives in Western Australia), Graeme Ferguson (a co-inventor of IMAX), Bernice Grafstein, Doris Mosdell, Sam Levene, Rae Direnfeld, plus more whose names I can’t at the moment recall. The first year of operations was spent learning the ropes and getting to know each other, and in our second year, I believe, I became program director.

From the early programs I have glanced at, it seems to me that I became a member of Toronto Film Society in 1949-50, although a lot of the TFS programming was recycled into the U of T Film Society showings. And that was through Dorothy, who encouraged us; she made suggestions, and I used to meet at her house out in High Park to co-ordinate the programs of the two societies. That’s where I met her husband, Oscar, who would be floating around in the background. Then we would knock off for half-an-hour, Dorothy would make coffee, and Oscar and I would fall into conversation about something we were both interested in–say, vaudeville. Oscar loved to reminisce about vaudeville, the Marx Brothers, and other performers. And that’s how we met.

Time rolled along and I was used to going to the Burritt’s place pretty regularly for meetings and screenings, though by the time I graduated they had moved downtown, (first, I believe, to a place on the south side of Bloor St. over near Sherbourne, and then to 130 Carlton St.) I seem to remember seeing many films for the first time not at TFS, but in the Burritt living room. You saw all kinds of things there that might or might not turn up on programs, and as a matter of fact, that’s where you met everybody and where I met Gerald. We have been friends ever since. If Stan Fox came into town he would turn up at the Burritts; if the Mekas brothers came to Toronto they would turn up there, so did Marshall MacLuhan–it was sort of Film Central. Anyone who knew anything about film, or wanted to find out anything came to the Burritts.

Oscar used to have a little projection booth there, built right into the living room. Later, as a television producer at CBC Toronto, I devised and produced a children’s series called Passport to Adventure and chose Elwy Yost as the host, who introduced and screened feature films shown in segments. I sketched out what was wanted on the permanent set, and it included Oscar’s projection booth, fitted in under the stairway of our set–so Elwy’s projection booth was really Oscar’s!

Well, four years zipped by. I’d been doing various things at U of T–acting and directing on stage, assisting on a couple of amateur movies, writing film reviews for Varsity, as well as studying literature & philosophy–then I graduated in 1952 and had to go out into the wide world–ideally suited for nothing! The University placement service gave me three slips of paper for job interviews. The only interesting one for me was the Assistant Editor of The CBC Times, so I went and had a 20-minute interview and I said I had written film reviews, and had a film society background. The interviewer later told me that the job had already been taken! But he added, “With your background, why don’t you try to get into television.” (I knew that television was coming to Canada, but imagined it was being planned in some secret underground silo in Red Deer, Alberta.) I said that I wouldn’t know what to apply for, or where, and he said, “Do you know anybody who works for the CBC?” and I said, “Yes, actually I know Oscar Burritt!” So he said, “Go and talk to him, maybe he can give you some advice.” So I did, and Oscard said, “Why don’t you apply as a studio director” (a floor director in television). I took Oscar’s advice and I ended up in the world’s most intellectual stage crew, almost none of whom had ever been stagehands before.

Five months’ later CBLT was on the air, with 80% of the programming on film and, unknown to me, the Film Dept. was frantically looking for staff. During camera rehearsal for an hour-and-a-half live television drama in Studio 1 (Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People), on which I was, by this time, Stage Crew Leader, in came Mavor Moore, the Program Director, to ask, “How would you like to work in the Film Dept.?” And this was again due to Oscar Burritt, who was Senior Editor there. It was he who told the TV brass, “Look, we are not going to go on the air next week unless we get somebody else in here.” And when they asked, “What do you expect us to do, walk out on Jarvis St. and buttonhole the first person who goes by?”, Oscar replied, “No, there’s a guy right downstairs who’s always hanging around up here. Ask him.” So that’s how I got into the Film Dept. and Oscar was my first boss in film.

Things moved fast at CBLT in those days and one night, when I had been in the Film Dept. for about a month, I was sitting there–feeling like a veteran by this time and holding the fort while Oscar was on a supper break–and a young woman stuck her head around the door and asked for Oscar. She had worked at Shelley Films with Oscar and others, and through Oscar had been offered a position as film editor. Her name was Cay Thomson, and I didn’t know I was looking at my future wife! Later on she got into film programming, one being CBLT’s International Cinema, a late-night show that Oscar Burritt used to introduce–maybe in the late fifties or early sixties. It had a striking introductory musical theme that people may recall taken from Jeux Interdits (Forbidden Games).

Getting back to the TFS…I left the U of T Film Society but stayed in TFS, where I saw many of the film which influenced my life; A Diary for Timothy, Rhythm of a City, The River, Muscle Beach, Listen to Britain, Begone Dull Care–and by the time I was Program Director of TFS around 1952-53, I had definite ideas. There were some people, I think, who joined film societies because it was “the thing” to do. There were no Sunday cinemas at that time and there were lots of reasons to join a film society besides being seriously interested in film. My unfavourite motivation of all was that of the kind of person who considered themselves, and even used the word: “discriminating”–they were ‘discriminating’ viewers. I hated that word because to me it meant they discriminated against everything they were prejudiced against. I recall one TFS member whose advice to the program director in an end-of-the-season questionnaire was; “Don’t waste time with American films.” Well, this immediately raised my hackles, the way it does at York University when students who like Hollywood cinema say, “I can’t stand those boring European films.” So, I was the kind of program director who was more into giving the members what I thought they ought to be exposed to, than what they thought they might like.

In those days the only serious book about film that I can remember was Paul Rotha’s The Film Till Now. There were, of course, the BFI magazines Sight and Sound, and Monthly Film Bulletin; and Sequence (that was my favourite among them), the latter edited by Lindsay Anderson and various other alumni of the Oxford University Film Society. And they were not discriminatory in the pejorative sense, and included good Hollywood films as well as European films in their consideration. All through the 1950’s new film societies and also new TV stations were springing up across Canada but I am convinced that Toronto Film Society and CBC-TV were the leaders, not only in programming, but technically and in terms of presentation. If I did anything notable while I was programming at TFS, it was to try to break down this prejudice against Hollywood genres and contemporary American films. We would devote complete evenings to theme programming, especially on such then “lowly” and disreputable genres as the Hollywood Musical or the Western. Both of these seemingly innocuous and politically uncontroversial genres–safe as far as Hollywood was concerned at the time–were entering a golden period during the McCarthy era.

In the “theme” showings we occasionally included extracts from feature films and even double-features if running times permitted. The idea was to demonstrate the celebratory thesis with a knock-out program of irrefutable quality. For the Western program, we expanded the program notes and, in addition to the films, I chose a group of historical still photographs for a slide presentation. Oscar shot all the slides using a macro-lens attachment on his 35mm still camera, and I wrote a voice-over commentary. These slides still exist, and I think the presentation was repeated a few years ago. Harry Purvis (still a TFS member) ‘read’ the commentary, but adlibbed a lot of new comments prompted by his encyclopaedic movie memory.

When films couldn’t be brought to Toronto we would arrange to go to where they could be seen, such as the Annual General Meetings of the Canadian Federation of Film Societies, following its establishment by Dorothy Burritt (Toronto), Dorothy McPherson (Ottawa) and Guy Coté (Montreal). Here, program directors form societies across the country could view interesting films not distributed in Canada, and decide whether their society would be interested enough to pledge to rent some of the films, for a fee set according to membership size. Program schedules were co-ordinated so that a single print could be bicycled around the country-wide CFFS circuit, with each committed society sending it on in time for the next scheduled exhibition date.

The two Dorothys (Burritt and McPherson)–kept track of the pledges, arranged the screening schedules, negotiated with foreign distributors and customs officials, generated and distributed information on the films for use by CFFS members before their screenings, and received and published program evaluations after the screenings.

Committed enthusiasts, of course, are often insatiable and in the early fifties we started a series of periodic TFS jaunts to the George Eastman House Archives in Rochester, NY., for weekends totally devoted to screenings in the adjoining Dryden Theatre–an enjoyable practice continuing to this day. There was a definite holiday exuberance to leaving your workaday world behind to join a congenial group of like-minded film buffs for a virtual orgy of historical screenings. One bright morning, in the exhilaration engendered by this excitement, and with the fortification of a good night’s sleep and a satisfying breakfast, I was impelled to utter to a car-full of fellow fanatic’s a stirring maxim that seemed to sum up our collective mindset: “Movies! They’re the only thing that’s real!” There was, of course, an undertone of deliberate ironic parody to this pronouncement bu nevertheless it still managed to express our perhaps too solemn commitment to film.

I remained a member of TFS for quite a few years; and I remember, when Dorothy Burritt was admitted to the Toronto General Hospital in 1955, I was walking along to see her and there was Christopher Chapman, with a movie camera, shooting a weed coming up through a crack in the concrete for his film The Persistent Seed! And I only knew him because of the Burritts and Toronto Film Society. I recall that we all went up to his place in the country after he’d won a Canadian Film Award for his film, The Seasons.

I loved Toronto Film Society and when it first started there were all kinds of reasons why it had to be–the films it showed could not be seen anywhere else during this pre-video and television age; however, it seemed to me there was much less daring and much less messianic commitment in programming. I lost the thrill, but I stayed on with the Silent Series which I still enjoyed, particularly if I could see films that were new to me. Fraser Macdonald was then programming it and preparing the scores. That, too, was probably one of the many things I learned in Toronto Film Society: to appreciate the scoring of films, silent and sound. I remember the first time I saw Broken Blossoms, one of my all-time favourite movies: Dorothy and Oscar had prepared a score that included the Benny Goodman Sextet’s version of Limehouse Blues as a motif that played over and over again. It sounds a bit improbable, but the counterpoint in mood and rhythm worked beautifully.

Dorothy and Oscar were creators who set standards in both the Canadian film society movement and the early days of English-language television in Canada. They served as teachers, mentors and models for a generation of film-minded people, myself included. I feel fortunate to have met them and privileged to have had them as friends.

************************************

Memories of Film Societies

The Pioneers – Dorothy & Oscar Burritt

by Stanley Fox

……………………………………………………………………………………

I hope that the role of Film Societies in the development of creative filmmaking in Canada will be recorded somewhere. I would have never considered that I could become a filmmaker in Canada if the Vancouver Film Society had not existed. It showed me great films that I would never have experienced in Vancouver’s commercial theatres. I was inspired to learn how to make films by those examples and by the creative atmosphere surrounding two of the pioneers of the film society movement, Dorothy and Oscar Burritt.

The first film society in Canada was incorporated in Vancouver in 1936. One of its founding members was Oscar Burritt. The society operated in 35mm in the Stanley Theatre on Sundays and had a membership of over five hundred.

My involvement with film societies began in 1946 with the chance finding of a folder in the public library advertising the founding of a group called The Film Survey Group. It was actually a re-birth of the original Vancouver Film Society which had suspended operations at the outbreak of war in 1939. I joined and quickly became friends with the executive, which included Dorothy Burritt. Dorothy allowed me to prepare musical accompaniments to the silent films from her large collection of records. After she discovered that I was interested in cinematography she offered me the loan of a very expensive 16mm Bolex camera which belonged to her husband Oscar, who was still in the Navy awaiting demobilization. It was the experience of using that camera which made me decide to make cinema my life work.

Filmmaking in Canada was a very exotic activity in the 1940s. Outside of the National Film Board there was almost no support for aspiring filmmakers. There was no Telefilm, no Canada Council, no external funding sources at all. The fact that some of us persevered was due in part to the support of people like the Burritts.