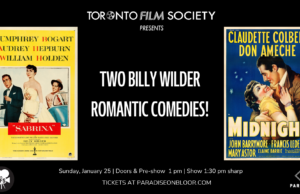

Midnight (1939)

By Toronto Film Society on October 20, 2025

Toronto Film Society presented Midnight (1939) on Monday, July 28, 1986 in a double bill with Murder at the Vanities as part of the Season 39 Summer Series, Programme 4.

Production Company: Paramount. Director: Mitchell Leisen. Producer: Arthur Hornblow, Jr. Assistant Director: Hal Walker. Screenplay: Charles Brackett and Billy Wilder, based on a story by Edwin Just Mayer and Franz Schultz. Cinematography: Charles Lang Jr. Art Direction: Hans Dreier and Robert Usher. Special Effects: Farciot Edouart. Editor: Doane Harrison. Miss Colbert’s Gowns by: Irene. Music: Frederick Hollander.

Cast: Claudette Colbert (Eve Peabody), Don Ameche (Tibor Czerny), John Barrymore (Georges Flammarion), Francis Lederer (Jacques Picot), Mary Astor (Helena Flammarion), Elaine Barrie (Simone), Hedda Hopper (Stephanie), Rex O’Malley (Marcel), Monty Woolley (Judge), Armand Kallz (Lebon), Lionel Pape (Edouart), Ferdinand Munier (Major Domo), Gennaro Curci (Major Domo).

Of all the recent films documenting the making of a film as it goes through the various stages of production, the screwball comedy Midnight might have ended up as one which was as lively as Leisen’s film itself, for the cast of characters who worked on Midnight were as eccentric as any which the scenarists, Charles Brackett and Billy Wilder, might have dreamed up. Right from their first meeting, the flamboyant Leisen clashed with the tempestuous Billy Wilder over changes in the script. There seemed to be no common meeting ground between Wilder, who believed that the script was not to be tampered with, and Leisen, who pragmatically believed that “If the actors couldn’t say a line, then we must give them something to say.” As a result of their conflict over rewrites, Wilder and Leisen became life-long enemies, and each believed that it was his particular talent which raised the film above the pedestrian to create a screwball comedy which some critics rank as one of the best made in Hollywood in the thirties. Wilder felt that Leisen was far too interested in the pleat of a costume or a rug on the floor. Leisen, on the other hand, believed that his lighter comic touch softened the cynicism of the Brackett/Wilder script resulting in a film which was more enjoyable for the audience while retaining “satire on class attitudes and its insights into the relationship between wealth and happiness.” In an interview with David Chiericetti, Leisen took great delight in recounting the story of a visit he made to a set of a film which Wilder was directing. Leisen found him furiously rewriting a script so that an actor could be more comfortable with the line. Of course, Wilder later had his revenge on the excesses of art directors in the film Sunset Boulevard, which logically incorporates into its brilliant design the clutter and rococo which too often overwhelmed and dominated the action of other films. What might have emerged had a film been made about the making of Midnight was the revelation that the creative chemistry which came from the clash of two wills as strong minded as Leisen’s and Wilder’s had as its result a more accomplished piece of work than they would have achieved had they worked with more accommodating collaborators.

Aside from the difficult Wilder, Leisen had to contend with John Barrymore, who dealt with the tension on the set by taking to the bottle more enthusiastically than he normally did. Though Leisen had hired Barrymore’s wife, Elain Barrie, to police her husband, Leisen still had difficulty keeping Barrymore in line, for he would relieve himself on the set as necessary and he refused to memorize his lines, relying on cue cards for his dialogue. Leisen seems to have had great patience with the eccentricities of his actors; he said that Barrymore was “sheer heaven, just fantastic” and he stated that he enjoyed working with Claudette Colbert, for he admired her instinctive sense of fashion. Although Leisen did not agree that the right side of Colbert’s face photographed better than the lift side, he went along with her demands in this regard. Colbert herself enjoyed working with Leisen, for he gave the actors a great deal of freedom to develop their roles. Though Leisen’s reputation as a director has fluctuated, one must admire the way that he orchestrated the work of the diverse personalities involved in this production to create a film which the New York Times described as “one of the liveliest, gayest, wittiest and naughtiest comedies of a long, hard season.”

Here follow, in characteristic vein, some of Midnight as glossed by Goerge Patterson of happy memory, when TFS showed the film in its 1969 Summer Series.

‘John Gillett on the occasion of the NFT’s Billy Wilder season in 1968: “Although overlooked at the time, Midnight has gained a considerable reputation of late as one of the best American comedies of the Thirties. In some ways, it has the elements of an American Regle du Jeu: a high-society gathering in a country mansion with some marvellously funny and confused relationships, all neatly wrapped in the Brackett/Wilder script and beautifully handled by Mitchell Leisen, one of Hollywood’s best craftsmen who was often as underrated as his films. And the playing is superb!”

John Baxter in his book Hollywood in the Thirties: Leisen’s masterpiece is the underrated Midnight, one of the best comedies of the Thirties. The Wilder/Brackett script is typically disenchanted and Leisen obviously found the story agreeable…There is a happy ending, but no plot twist can dispel the film’s essential bitterness. Like all Leisen films it is callous and cynical, its style faultless, its design superb. One cannot doubt that his is a major talent, sadly neglected.

But if you think those chaps are Midnight-happy, just listen to Charles Higham in Sight and Sound, Spring 1963: In 1939 Ninotchka and Midnight were released: both set in Paris, they showed Wilder and Brackett at the top of their form. Midnight was easily Ninotchka‘s equal, but has been almost totally forgotten, perhaps because its director, Mitchell Leisen, has never been a critics’ pet. Splendidly upholstered in the best Paramount-Hans Dreier tradition, it gives a stylized but penetrating exposition of an upper class that vanished almost immediately after the film was completed, with the outbreak of World War Two. The parallel with Renoir’s Règle due Jeu, made in the same year and on much the same territory, hardly needs stressing.

Higham goes on to speak of “a superbly funny piano recital”, “a classic card game”, “a wonderfully played and written scene” with Francis Lederer at Colbert’s bedroom door; and further tells us that “Mary Astor plays with glittering malice”, that “Hedda Hopper leads a conga line with irresistible elan”, and that “Barrymore hilariously impersonates a little girl on the telephone”. He sums up: “Brittle, heartless and stylish, this film remains one of the peaks of Wilder’s career”.

Fine and dandy, but–Ninotchka‘s equal? Parallels with La Regle du Jeu? Wow, I don’t know. But if Midnight stands up even half as well as these gentlemen suggest, we should be in for something of a treat.

Adapted from previous notes by G.G. Patterson, and Barbara Michel

You may also like...

-

News

Thank You from TFS!

Toronto Film Society | July 21, 2025Our matinée on Sunday, August 17th – at the blessedly air conditioned Paradise Theatre – will conclude the Toronto Film Society’s 77th season! But take heart, as we’ll be...

Programming

Virtual Saturday Night at the Movies

Toronto Film Society | January 25, 2026Toronto Film Society will be screening Sabotage (1936) straight to your home on Saturday, February 28, 2026 at 7:30 p.m. (ET)! Directed by Alfred Hitchcock, starring Sylvia Sidney, Oscar...

-

Toronto Film Society | January 25, 2026

Toronto Film Society | January 25, 2026

-

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

-

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Donate to Toronto Film Society – We’re now a Registered Charity!

Copyright © 2017 Toronto Film Society.