A Place in the Sun (1951)

Toronto Film Society presented A Place in the Sun (1930) on Monday, March 27, 1978 in a double bill with Min and Bill as part of the Season 30 Monday Evening Film Buff Series, Programme 8.

Production Company: Paramount. Producer/Director: George Stevens. Associate Producer: Ivan Moffat. Screenplay: Michael Wilson and Harry Brown, after the Patrick Kearney play based on Theodore Dreisler’s novel “An American Tragedy”. Photography: William Mellor. Art Direction: Hans Drier and Walter Tyler. Costumes: Edith Head. Music: Franz Waxman. Editor: William Hornbeck.

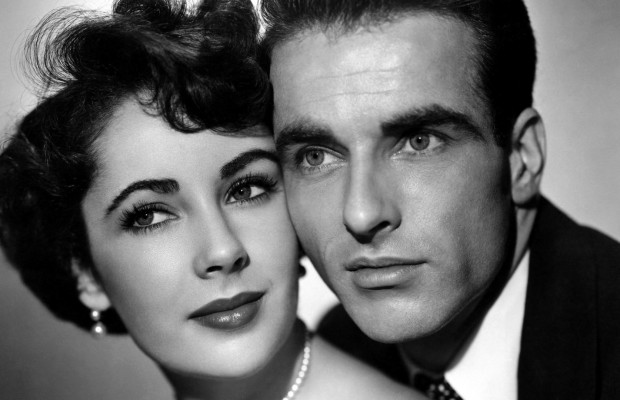

Cast: Montgomery Clift (George Eastman), Elizabeth Taylor (Angela Vickers), Shelley Winters (Alice Tripp), Anne Revere (Hannah Eastman), Raymond Burr (Marlowe), Herbert Heyes (Charles Eastman), Keefe Brasselle (Earl Eastman), Shepperd Strudwick (Anthony Vickers), Frieda Inescort (Mrs. Vickers), Ian Wolfe (Dr. Wyeland), Louis Chartrand (Marcia Eastman), Fred Clark (Bellows), Walter Sande (Jansen), Douglas Spencer (Boatkeeper), John Ridgley (Coroner), Kathryn Givney (Mrs. Eastman), Ted de Corsia (Judge), Charles Dayton (Kelly).

A Place in the Sun, judging from the competition so far, is the picture to beat for 1951’s Academy Awards. [Unfortunately although nominated (as were both Clift and Winters) A Place in the Sun lost to An American in Paris. Stevens, Wilson and Brown, Mellor, Hornbeck, Head and Waxman did however all receive Oscars.] Producer-Director George Stevens’ modern version of the late Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy is at once a faithful adaptation of the novel, an artful job of movie-making and an engrossing piece of popular entertainment.

Novelist Dreiser, who was outraged at Hollywood’s earlier version of his book, might well have felt flattered by the new one. No director could hope (or want) to reproduce the mass of detail which Dreiser took from life to fill out the case history of a young man charged with the murder of his cast-off sweetheart. Movie-maker Stevens, working with an intelligent script by Michael Wilson and Harry Brown, captures the power of the novel without its heaviness, the insight without the inventories. The story still flows inexorably from the springs of character and environment. And though Stevens concentrates on its poignant love affairs, he neither overlooks Dreiser’s implied social comment nor oversimplifies it with trite labels.

A Place in the Sun is the story of George Eastman, a poor, ambitious boy who pursues the dream of a Horatio Alger hero to his own undoing. He hitchhikes to the distant city, where his rich uncle manufactures swim suits on the vast scale and cuts a swath in local society. There, from a shipping clerk’s job in the factory, George catches tempting glimpses of a life of wealth, glamour and importance….

Thanks to Director Stevens, all three oft he picture’s stars do the best acting of their careers. In the pivotal role, Actor Clift’s sensitive, natural performance gives the film a solid core of conviction. Actress Taylor plays with a tenderness and intensity that may surprise even her warmest fans. In a film of less uniform excellence, Shelley Winters’ mousy factory girl would completely steal the show. Shy, petulant, or shrilly nagging by turns, she makes the most of her unconventional role and of the movie’s boldest scene, when she gropes, on a choked-up brink of tears, for a tactful way to ask a doctor for an abortion.

But no one can steal the show from Producer-Director Stevens, whose firm grip is on every foot of A Place in the Sun. Stevens’ unerring timing, and his skill at filling any situation with the last shade of emotion and meaning, enable him to direct the picture at a deliberately slow pace that still weaves a spell without dragging for a moment.

He makes imaginative use of his sound track: the cry of a loon, the distant whine of sirens, the barking of dogs become recurring motifs bound up with the action. His camera is effectively restrained; it peeks through doorways or stands patiently in the corner like a hidden witness; and when it moves suddenly into close-ups, the effect of intimacy is breathtaking. The film’s seduction episode is a textbook example of director’s magic. The players, barely visible as dim silhouettes, are no less Stevens’ raw materials than the sounds, shadows and camera movements. And he molds and shapes them into probably the frankest, most provocative scene of its kind yet filmed in Hollywood.”

Time, September 10, 1951

It would have been an easy matter to label George Stevens’ A Place in the Sun Hollywood’s most impressive picture this year if, at virtually the same moment, Warner Brothers had not unveiled an equally impressive production by Elia Kazan of A Streetcar Named Desire. Coming together they are rather an embarrassment of riches, wholly adult fare and some proof, at least, that Hollywood can cast aside, when it wants to, all those restrictive pressures that are supposed to be keeping the American screen from acknowledging the facts of life.

If there is to be an argument about which has done more or better, the nod might go to Stevens, for, in a sense, his was the harder job–to boil down the 840-page bulk of Dreiser’s “An American Tragedy” to two hours on film, to keep intact its universal values, to change or remove any which might no longer have relevance. The major change involved was to give the story a contemporary setting. According to my information it was Stevens (although the screenplay was done by Michael Wilson and Harry Brown) who decided that this would be preferable to making it a period piece. Dreiser’s novel was published in the mid-Twenties; the actual case on which it was based had occurred twenty years earlier. A big question for Stevens must have been: could the dramatic force of the original situation be kept if couched in present-day terms? The answer lies in the conviction that has been given a fresh treatment, the convincingness with which the actors have played it. The result is in the nature of a victory over material that might very well have appeared dated.

Dreiser’s view of his characters was probably sound enough, but he was mainly concerned with revealing a villainous society whose forces were responsible for Clyde Griffith’s dilemma. (The movie gives him the name of George Eastman). The Stevens film somewhat softens and humanizes this view, makes Dreiser’s clear-cut class demarcations less rigid, and puts as much emphasis upon psychological factors as upon the societal. As we see him here, George Eastman responds to the countless proddings from his environment (the billboards with their pictures of indolent girls proddings from his environment (billboards with their pictures of indolent girls in bathing suits, the obscenely yellow Cadillacs, the obvious difference between being a bellhop and member of a wealthy and prominent family) and he starts pathetically climbing towards his dream of “success”. His forlorn upbringing by a street missionary family has made him all the easier prey to the situation he falls into. There is a great loneliness in him, too, and ready to be called out in him is the hidden, psychopathic streak in his nature. Those who remember Clyde in the novel will see how important this character change is. Presented as Dreiser had him he would seem utterly weak and mooning, perhaps not worth the brother of being re-created today. The two girls in George’s life have also been made more sympathetic, in the sense that an audience can respond to them more fully. In other respects there is less change to Dreiser’s intent.

An American Tragedy was made into a movie once before, a 1931 Von Sternberg model that had the novelist himself up in arms against it. The picture distorted the book’s meaning, he felt, to the very opposite of his intention, justified society and turned in an indictment of the young man. One wonders if A Place in the Sun would have mollified him. Allowing for the elimination of the long section dealing with George Eastman’s boyhood, the pattern of the story has been kept relatively close to the book with an ending that is very similar to Dreiser’s.

Montgomery Clift, one of Hollywood’s most gifted and engaging young actors, adds considerably to his stature with his portrayal of George Eastman. Moody and complex, one senses the dark hauntings of his youth, the intelligence hampered b the lack of opportunity to use it. Clift, of course, had George Stevens to discuss and probe with him the nature of the character, and this ability of the director to make actors see what he wanted paid off astonishingly with the female roles. Elizabeth Taylor is a joy to watch as the charmingly spoiled Angela (one had somehow never conceived of the glamorized creature as an actress) who spontaneously, out of girlish and unaffected infatuation, offers George his chance to enter a world of prominence and ease. And as Alice Tripp, the girl from the painfully mundane and restricted background, Shelley Winters (the sexiness hidden, the legs undisplayed) achieves almost a tour de force of naturalness. She is drably commonplace, pathetic and appealing at the same time, genuinely frightened and miserable. There are scenes that nakedly reveal all that is going on in her mind: the visit to the doctor who refuses to help her; the boat ride with George–her death but moments away–when she babbles with heartwrenching enthusiasm of a life together that is everything he fears. Scene after scene distills the meaning of events that Dreiser took long pages to unfold.

The novel gained its effects largely by its massive accumulation of detail (the writing is for the most part irritating and clumsy); the technique of the movie is vastly different. Here each scene must accomplish its objective with vividenss and economy; dialogue is often scrapped in favor of the visual symbol. From moment to moment, in fact, the two distinct kinds of telling, interwoven as they are, can be discerned, as the symbolic image accompanies the realistic level of the happenings. Now and then a line of dialogue does get out of key, very occasionally the symbol grows obtrusive, but in each case never enough to seriously disturb. One has, at the end, the feeling of a screen that has been illumined in a new way by a hand altogether accomplished.

Saturday Review by Hollis Alpert, September 1, 1951

Notes compiled by Glen Hunter

Leave a Reply