Death Takes a Holiday (1934)

Toronto Film Society presented Death Takes a Holiday (1934) on Monday, July 14, 1986 in a double bill with Hands Across the Table as part of the Season 39 Summer Series, Programme 2.

Production Company: Paramount. Producer: E. Lloyd Sheldon. Director: Mitchell Leisen. Screenplay: Maxwell Anderson, Gladys Lehman, Walter Ferris, based on the play by Maxwell Anderson, adapted from the play by Albert Casella. Photography: Charles Lang. Art Direction: Ernst Fegte.

Cast: Fredric March (Prince Sirki), Evelyn Venable (Grazia), Sir Guy Standing (Duke Lambert), Katherine Alexander (Alda), Gail Patrick (Rhoda), Helen Westley (Stephanie), Kathleen Howard (Princess Maria), Kent Taylor (Corrado), Henry Travers (Baron Cesarea), G.P. Huntley, Jr. (Eric), Otto Hoffmann (Fedele), Edward Van Sloan (Doctor Valle), Hector Sarno (Pietro), Frank Yaconelli (Vendor), Anna De Linksk (Maid).

Death, moving from the battlefields of the First World War, scarcely took much of a holiday in the theatre of the 1920s and the cinema of that and the following decade. Though he was associated most often with the soldier’s or gangster’s gun, he made as well several appearances in persona in a group of fantasy films, many based on successful plays, a group large enough to draw the attention of historians of the period. Such works as Somerset Maugham’s last play Sheppey, and such plays and films as Outward Bound, The Passing of the Third Floor Back, The Return of Peter Grimm, make up a considerable subgenre, in which Death, or some traveller from the other world, moves among the living, or else the living–usually rather to their surprise–find themselves to be dead. There had been a great vogue for such material, led by The Gates Ajar, in post–Civil War America; and the impulse is no doubt the same in each case: in the aftermath of a great war in which most families lost a loved one, it was comforting to fantasize for a time, mostly untroubled by obtrusive religious dogma, that one did indeed survive death. The treatment would become more comic and irreverent in the 1940s, on both sides of the Atlantic (though there were still films like The Human Comedy or A Guy Names Joe), with Blithe Spirit, Here Comes Mr. Jordan, Heaven Can Wait; but Death Takes a Holiday is in every way a reverent and @serious@ film. Albert Casella’s play had been successful enough for Maxwell Anderson, whose Winterset in particular had made him one of the most esteemed playwrights of the American 20s and 30s, to be moved to adapt it, and the reaction to the play and the film can best be gauged from Leisen’s own words: “We had seven or eight thousand letters come in from people all over the country, saying that they no longer feared death. It had been explained to them in such a way that they could understand the beauty of it.”

In Death Takes a Holiday Leisen has not yet hit his stride; the film is broadly uncharacteristic. The Leisen touch is, however, present in the emphasis on sets, which all but become characters in the drama, and are clearly charged with a symbolism which reminds one of Sternberg, who complained bitterly that Leisen had plagiarized the sarcophagi prepared for The Scarlet Empress, that same year. The lighting and camera movement, too, wonderfully convey the sense of fantasy. All these effects come together in the sequence following the opening, as the party drive back to the palazzo, their cars pursued by the enveloping shadow of Death. As they enter the palace, a crane follows them ever deeper into the corridors lined with the ancestral dead. Following the lively opening of the film at the wine festival, this second scene sets the mood of the whole production, with its brooding, even morbid, mingling of light and shade, and its intimations of the fear excited in all the characters but Grazia.

Yet Grazia is finally too eccentric a character to hang the theme of the beauty of death on. Viewed in realistic terms–and doesn’t film always invoke these?–she is a morbid girl, more than half in love with easeful death, who goes gently into the good night at the end. She has no will to live, literally, and it may be difficult to identify with such a character. Caught between her two lovers, with Kent Taylor chosen for his role because he looked like the living double of March, she chooses death over life, and though her final merger with Death is both climactic and powerful, it has, especially to a late twentieth-century audience, a touch of the bogus.

Leisen’s brooding fantasy effects are, of course, amply buttressed by the full panoply of Paramount talent. Charles Lang had won an Oscar the year before for photographing A Farewell to Arms, but some of his most characteristic effects in black and white contrast were achieved in films dealing, comically or seriously, with the ghostly: The Cat and the Canary, The Ghost Breakers, The Uninvited, The Ghost and Mrs. Muir. And Ernst Fegte, who would share an Oscar with Hans Dreier for a later Leisen film, Frenchman’s Creek, and whom Leisen called “one of the most brilliant art directors of all times” (Leisen didn’t get on well with the clearly superior Dreier), emphasizes in his comments on Death Takes a Holiday the ensemble aspect of the work in the film–“a group of compatible people got together on a picture and they were so sensitive and aware of each other’s talents that it was wonderful.”

The stars, too, make up much of the picture’s appeal. Fredric March was already a well-established star and actor, two years after Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, two years before A Star is Born. The roles of Count Vronsky, Anthony Adverse, and Wally Cook were still to come, but in 1934 he made six films, including The Affairs of Cellini and The Barretts of Wimpole Street. His performance here, with its portentous enunciation and its well-sustained foreign accent, drew the chief praise of the critics. Evelyn Venable’s performance was also much admired; she had appeared in Leisen’s first film as director of credit, Cradle Song, and the role of Grazia was perhaps the highpoint in the career of this fragile (here even moribund) beauty. Henry Travers and Helen Westley, two of the most famous character actors of their time, give characteristic portrayals, and Sir Guy Standing, who did not live long enough to become Sir C. Aubrey Smith, gives a performance which shows, in the best sense, his stage background; he belonged to a theatrical dynasty, in fact, the father of Kay Hammond and grandfather of John Standing.

Death Takes a Holiday was a big success at the box office of 19344, second only, if we accept Leisen’s own statement, to another Paramount production, She Done Him Wrong. (Obviously the Life in her men was stronger than Death!) Variety called it “the kind of story and picture that beckons the thinker. . . . Out among the whistle stops it may fool like others have,” and the picture’s popularity in its time is surely to be attributed to the sentimental reaction of the general public, and the approval of what Variety liked to call “the intelligentsia.” It is improbably that, fifty years later, either audience will take to it in quite the same way.

Notes by Barrie Hayne

Sunday Afternoons at the Paradise

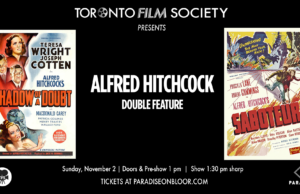

Join TFS for Season 78’s Sunday Matinée Series generously sponsored by our good friend, author and documentary filmmaker, Mr. Don Hutchison. Please save this date and visit us regularly...