Double Indemnity (1944)

By Toronto Film Society on May 14, 2021

Toronto Film Society presented Double Indemnity (1944) on Tuesday, July 29, 1969 as part of the Season 21 Summer Series, Programme 3.

Sahara Hare USA 1955 approx 7 mins colour 16mm

Production Company: Warner Bros. A Looney Tune cartoon. Director: I. (“Friz”) Freleng. Story: Warren Foster. Voice Characterizations: Mel Blanc. Music Direction: Milt Franklyn. Colour: Technicolor.

Cast: Bugs Bunny.

The ’30’s and ’40’s were the heyday of animated cartoon production in Hollywood and during these decades all the major studios had their own animation units. Nevertheless, all through the ’30’s the Disney studio dominated the field both artistically and commercially. Mickey Mouse had to be the most popular cartoon figure of that decade, surpassing even Popeye the Sailor, his nearest rival.

In the ’40’s both these characters were superseded by a new and more sophisticated group. Donald Duck came to the fore in the Disney films, and even his popularity was outdistanced by that of Tom and Jerry at MGM, and, at Warners, by that of perhaps the biggest single cartoon star of the new decade, “Bugs” Bunny, a character developed in 1938-9 by Tex Avery and Chuck Jones.

Here’s how Richard Schickel explains it in his recent book, The Disney Version:

With many of his best men gone and those remaining concentrating on features, the little cartoons responsible for his [Disney’s] first fame suffered seriously. The Warner Brothers cartoon department, headed by a Disney graduate, into what has been termed “La Grande Epoque”. Its star, Bugs Bunny, was as urbane as the Mouse [Mickey] was rural, and infinitely more versatile than any of the Disney gang, each of whom had limits. The Duck, for example, was barred from verbal humor because of his deliberately garbled voice; The Goof had, built in, a stupidity problem; Pluto, of course, had neither voice nor brains; Mickey, finally, was now too nice to be a comedian. Bugs, on the other hand, could do everything. The inimitable voice, supplied by Mel Blanc, could push home a punch line in the same deft manner that the radio comedies of the time had taught us to appreciate; the body was built for speed, and the chases that were the high points of his films were masterfully constructed. Finally, and most important, The Bunny’s personality perfectly suited his times. He was a con man in the classic American mold, adept in the technique and ethics of survival, equally at home in the jungle of the city and in Elmer Fudd’s carrot patch. In the war years, when he flourished most gloriously, Bugs Bunny embodied the cocky humor of a nation that had survived its economic crisis with fewer psychological scars than anyone had thought possible and was facing a terrible war with grace, gallantry, humor and solidarity that was equally surprising.

Notes by Doug Davidson

One A.M. USA 1916 2 reels b&w 16mm

Released by Mutual, August 7, 1916. Written and Directed by: Charles Chaplin. Photographed by: William C. Foster and Rollie Totheroh.

Cast: Charles Chaplin (the reveller), Albert Austin (the taxi driver).

This is No. 4 of the twelve shorts produced by Chaplin for the Mutual company which are the classics of his two-reel comedy days. Presumably he was running out of ideas for the moment, for this solo performance (the taxi driver’s appearance is barely a flash) is simply one of Chaplin’s old comedy routines in his old music-hall days with the Fred Karno company. This explains why it is not a typical Charlie Chaplin film.

Charles Spencer Chaplin was born on April 16, 1889, of theatrical parents, and began his own show-business career at the age of seven in a music-hall act. He was a boy actor in legitimate drama from the age of twelve, including three years in the popular “Sherlock Holmes”. Finally, at seventeen, he got a job with the Fred Karno Company–or rather, with one of at least thirty companies this former acrobat and comedian ran simultaneously. They featured knockabout comedians, with a large repertoire of skits and comedies, and were popular in the English music-halls (typical titles: “Jail Birds”, “The New Woman’s Club”, “The Dandy Thieves”)–their characters were usually drunks coming home, pool-hall sharks, punch-drunk boxers, and so on. Such was Chaplin’s valuable training in comedy; he was a member of the Karno companies from 1906 to 1913, during which time he rose to be one of their leading comedians. (Another member was Stan Laurel; so was Albert Austin, who later joined Chaplin in Hollywood.#) In 1909 the company visited the Continent and appeared at the Folies Bergères in Paris; and in 1910 it went to North America, and toured for at least three years, with only one visit home. By the end of 1913 Chaplin, his contract for the tour finished, left for California to take up the year’s contract he had signed with Mack Sennett.

While it didn’t take Chaplin long to adapt himself to the silent film medium, his theatre background is reflected in the fact that basically he has always bee more interested in what goes on in front of his camera than in doing fancy things with camera angles or editing. What he does use his camera for is to shoot each scene over and over until it is perfect. The split-second timing that one admires in Chaplin’s gags represents the one good “take” after innumerable unsuccessful tries.

Chaplin spent all of 1914 working for Sennett’s Keystone Comedies, 1915 working for the Essanay Company, and 1916 and the first half of 1917 making the dozen two-reel comedies required by his contract with the Mutual company–their titles being The Floorwalker, The Fireman, The Vagabond, One A.M., The Count, The Pawn Shop, The Rink, Easy Street, The Cure, The Immigrant and The Adventurer.

Several of his films he made in those three-and-a-half years were based on some of his music-hall routines for Karno; One A.M. is one of them.

(# He’s the taxi driver in One A.M.)

Notes by Fraser Macdonald

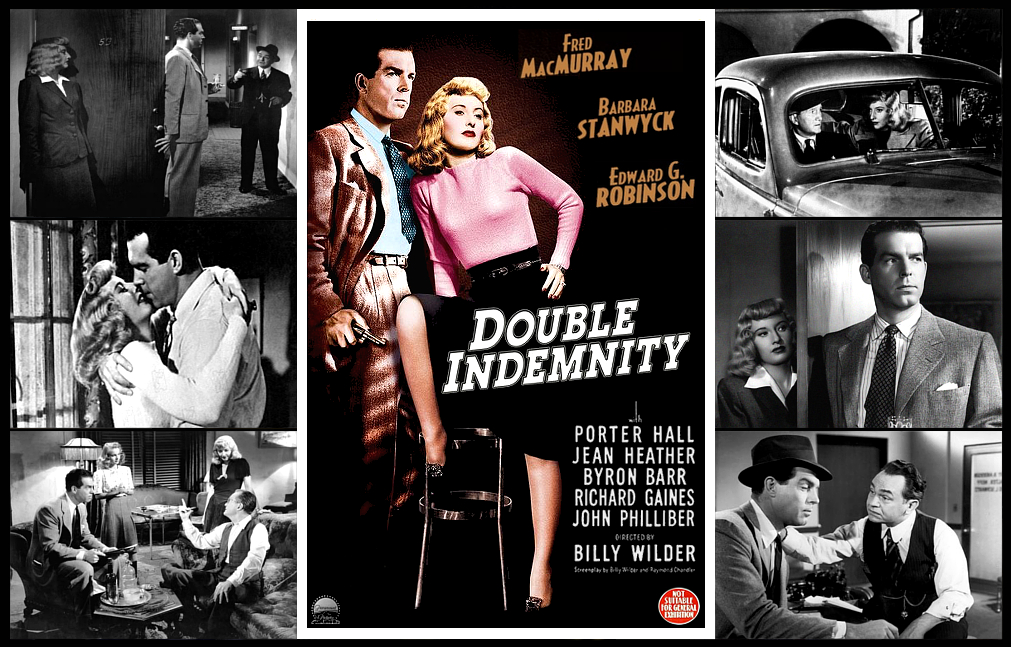

Double Indemnity (1944)

Production Company: Paramount. Producer: Joseph Sistrom. Director: Billy Wilder. Screenplay: Billy Wilder and Raymond Chandler, based on the novel by James M. Cain. Assistant Director: C.C. Coleman, Jr. Photography: John F. Seitz. Editor: Doane Harrison. Art Direction: Hans Dreier, Hal Pereira. Set Decoration: Bertram Granger. Music: Miklos Rozsa, with Symphony in D Minor by César Franck. Sound: Stanley Cooley.

Cast: Fred MacMurray (Walter Neff), Barbara Stanwyck (Phyllis Dietrichson), Edward G. Robinson (Barton Keyes), Porter Hall (Mr. Jackson), Jean Heather (Lola Cietrichson), Tom Powers (Mr. Dietrichson), Byron Barr (Nino Zachette), Richard Gaines (Mr. Norton), Fortunio Bonanova (Sam Gorlopis), John Philliber (Joe Pete), Betty Farrington.

“The best films of 1944? Henry V of course and Double Indemnity. You can never feel the same about Kingship after hearing Olivier’s ‘Upon the King’ soliloquy; and you can never feel the same about Lust again after seeing Stanwyck’s ankleted legs coming down the stairs.”

So said lady critic in a London paper, and perhaps she overstated her case; but Billy Wilder’s movie certainly elicited a splendid crop of notices when it opened in the West End–tantalizingly splendid for a movie-buff in the Canadian Army Press Camp somewhere in Holland, lavishly supplied with the latest papers telling us of films we couldn’t often see, until that next precious London leave. At this point a well-meaning aunt in Philadelphia escalated my frustration by sending me a Quaker City movie-page–prominently advertising guess-what. But came a day when the grapevine indicated that Double Indemnity would actually be shown at a free-for-soldiers performance in the movie house in a reachable Dutch town on a certain afternoon; though the only way you could get there from our area was to hitch a ride in some military vehicle, a common experience in many parts of Europe then–the movies you wanted to see always seemed to be on in another town. Along the road, British Tommies would always pick you up, fellow-Canadians sometimes, Americans never. On this particular day, after much thumbing, I managed to make my way to the other town, in time for the show, saw Double Indemnity and was well-satisfied. Hitching my way back to camp, I lingered in the messhall after supper, idly wondering what tattered film, until now unspecified, our own 16mm unit was going to project that night. You guessed it! Our Sergeant got to his feet and affably announced that we had a special treat in store tonight–a new movie called Double Eye-Demnity. (OK, so I sat through it again–I had maybe something better to do?)

Although restrained indeed as compared with present-day sex-and-crime films, Double Indemnity was a bold movie for its time. After the Legion of Decency crackdowns and boycotts circa 1933-4, Hollywood producers had been pretty cautious in their approach to any kind of strong subject-matter for some years, and this tough James Cain story had gone the rounds of several major studios and been rejected right down the line–but finally Wilder and Chandler came up with a treatment that Paramount found acceptable in spite of the Hays Office feeling that it presented “a clear blueprint for a perfect crime”. Even then, Barbara Stanwyck and Fred MacMurray were hesitant about playing adulterous murderers, MacMurray especially holding out for some time while other actors were approached. “When George Raft turned it down”, quipped Wilder, “we knew we had a good picture”.

The story of an insurance salesman who plots with a client’s wife to kill him, make the murder like an accident, and collect the insurance money, it presented (in spades, as they say) an anti-hero-and-heroine many years ahead of Bonnie and Clyde and considerably less sympathetic at that. The tale is told and the characters examined with a total lack of sentimentality, softening or glamourizing; the husband-victim is himself an insensitive slob, and even Edward G. Robinson’s insurance investigator, while portrayed as a man with a certain human compassion, leaves one with the uneasy feeling that his ruling passion is really cracking every case and saving the money for his company at all costs–there’s an infallible “small man inside him” that always tells him what’s what and how to operate. At times studio-bound but in several important instances location-shot, the film details the sleazy backgrounds and haunts of its corrupt urban-California denizens with acid accuracy. The style is tense and controlled, and pace deliberate but compelling, the camerawork and lighting aiding much in evoking the mood of gradually impending doom. Although Raymond Chandler expressed unhappiness over his script collaboration with Wilder, the dialogue is sharp and idiomatic, the incidents tautly developed.

Double Indemnity is the first Wilder film of consequence, and the first full-blooded expression of the caustic, pessimistic, cynical and disenchanted Wilder view (whether in drama, melodrama or comedy) of the American scene. In some quarters it has been charged with cheapness, coldness and lack of depth; accused of exploiting pseudo-realism rather than making a genuine social criticism. But generally the film and the performances have been, I think rightly, praised. And its box-office success paved the way for Wilder being allowed to tackle other risky themes like The Lost Weekend and Sunset Boulevard.

Footnote: The original version of Double Indemnity ended with a 20-minute sequence showing the MacMurray character’s execution in the gas-chamber. This was eliminated after the first preview.

Notes by George G. Patterson

References:

Billy Wilder by Axel Madsen

Film Heritage, Summer 1967

Dilys Powell, The Times, September 17, 1944

Sight and Sound, Spring 1963, Winter 1967-68

Agee on Film (James Agee)

National Film Theatre (London) brochures, February-March 1964, July-August 1964

You may also like...

-

News

Frances Blau

Toronto Film Society | February 27, 2024On Monday, February 26th, 2024, Toronto Film Society lost longtime friend, supporter, and board member Frances Blau. Known for her sense of humour, her love of film, her generosity,...

-

Special Events

The Ladykillers (1955) at the Paradise Theatre

Toronto Film Society | March 9, 2024Toronto Film Society presents Targets (1968) at the Paradise Theatre on Sunday, April 7, 2024 at 2:30 p.m. Ealing Studios arguably reached its peak with this wonderfully hilarious and...

Programming

Virtual Saturday Night at the Movies

Toronto Film Society | April 11, 2024Toronto Film Society is back in the theatre! However, we’re still pleased to continue to bring you films straight to your home! Beginning Season 73 until now we have...

4-

Toronto Film Society | March 9, 2024

Toronto Film Society | March 9, 2024

-

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

-

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Donate to Toronto Film Society – We’re now a Registered Charity!

-

Copyright © 2017 Toronto Film Society.

Leave a Reply