Hands Across the Table (1935)

By Toronto Film Society on June 30, 2025

Toronto Film Society presented Hands Across the Table (1935) on Monday, July 14, 1986 in a double bill with Death Takes a Holiday as part of the Season 39 Summer Series, Programme 2.

Production Company: Paramount. Producer: E. Lloyd Sheldon. Director: Mitchell Leisen. Screenplay: Norman Krasna, Vincent Lawrence, Herbert Fields, based on “Bracelets,” by Vina Delmar. Photography: Ted Tetzlaff. Music and Lyrics: Sam Coslow, Frederick Hollander. Costume Design: Travis Banton.

Cast: Carole Lombard (Regi Allen), Fred MacMurray (Theodore Drew III), Ralph Bellamy (Allen Macklyn), Astrid Allwyn (Vivian Snowden), Ruth Donnelly (Laura), Marie Prevost (Nona), Joseph Tozer (Peter), William Demarest (Natty), Edward Gargan (Pinky Kelly), Ferdinand Munier Niles, (the Butler), Harold Minjir (Couturier), Marcelle Corday (French Maid), Nell Craig (Saleslady), Jerry Mandy (Head Waiter), Phil Kramer (Waiter in Supper Club), Murray Alper (Cab Driver), Nelson McDowell (Man in Night Shirt), Sam Ash (Maitre d’Hotel), Ed Pel (Barber), Jerry Storm (Barber), Francis Sayles (Barber), Chauncey M. Drake (Barber), Sterling Campbell (Barber), Herman Bing (Proprietor of Delicatessen).

After five films at paramount as director of record, Mitchell Leisen’s career, despite the success d’estime of Death Takes a Holiday, hung in the balance. His sixth film, Four Hours to Kill, was a routine assignment which happily proved successful at the box office. However, he still “ached for comic opportunity,” as one writer puts it; he had sought the sound version of Ruggles of Red Gap, which had gone instead to Leo McCarey. When Carole Lombard, therefore, requested him as the director of her next picture, Hands Across the Table, he took it with both hands.

If in Death Takes a Holiday he seems not quite to have found his touch, in Hands Across the Table he was working for the first time in the genre in which his best work would be done, the “screwball” comedy. Like stage Restoration comedy, this form is coterie and highly formulaic (“The plot here is Group A, Subtype 11-C,” as Otis Ferguson wrote in the New Republic). It is also highly admiring of the upper classes, in this case the American rich: the screwball heroine is as mercenary in her husband hunting as Mrs. Benntt ever was, and this is a truth universally acknowledged by the good characters in these films. There is a fairy tale motif at work as well here: the hero’s wealth is often not known to the heroine (as in Easy Living or My Man Godfrey); he is a handsome prince disguised as a penniless frog, and she is rewarded at the end with his unexpected riches. Even when, not infrequently, she too is an heiress, her shrewishness must be tamed beofre she and the hero can share the wealth (as in It Happened One Night), or else the hero is quite as rich as she (as in The Philadelphia Story). The ethos of these films may be summed up in the words of the song from the musical version of one of them–“Who Wants to be a Millionaire?”–answered, as the film if not the song answers it; “Everybody Does!”

Hands Across the Table was the first film to be seen through all its stages by Paramount’s new head of production, Ernst Lubitsch. It is difficult to imagine “the one and only” making a pure screwball comedy, since his admiration of the rich was too diluted with a characteristic skepticism. But the Lubitsch touch is everywhere here, as the New York Times observed, and it is here in the typical inversions of the formula. Regi Allen is a working girl pursuing the rich playboy Theodore Drew 3rd. So far, so good. What Regi doesn’t know is that the Drews have lost all their money in the Crash. (“Maybe you heard about the Big Crash? Well, that was, uh, us”); and Theodore too is looking for a rich mate, not a manicurist. The extremely rapid pace of the picture is very much a la Lubitsch, and one of the funniest scenes, with Carole impersonating a telephone operator while MacMurray calls his rich fiancée ostensibly from Bermuda, though actually from Regi’s Manhattan apartment, where he is staying, loses all sense of being the vaudeville act it might well have become, and is fully integrated into the film in a very Lubitschean way.

Carole Lombard was the quintessential screwball heroine, and is totally identified, in all her best films (Twentieth Century, My Man Godfrey, Nothing Sacred, To Be or Not To Be) with the form or variations on it. (The other great female exponents of screwball, Jean Arthur and Claudette Colbert, had a wider range, as Colbert’s in Cleopatra and Drums Along the Mohawk, make clear; and we are reminded that Lombard, except for her last film, To Be or Not To Be, rarely worked for major directors, and then usually in their minor films (Mr. and Mrs. Smith). Working at Paramount for the Leisens, the William K. Howards, the Wesley Rugglesses, she may have fallen into the screwball roles–and is anyone complaining?–out of natural affinity and lack of strong individualistic direction. But, on the evidence of such films as Vigil in the Night and They Knew What They Wanted, her audiences accepted her only in the screwball roles.)

Carole Lombard may be said to be the real driving force behind Hands Across the Table, more than Leisen himself. She had taken a proprietary interest in Leisen since appearing in his second film, The Eagle and the Hawk. (As her biographer ntoes, when Gable complained that she had no women friends, but only predatory males, she replied that some of her best friends were women–“Why, there’s Billy Haines, and there’s Mitch Leisen”–so there was a natural affinity there). Having asked for him as director in Hands Across the Table, she rehearsed the film completely before it went into production, and even before the leading man was cast, she and Leisen huddled together constantly, sometimes with Lubitsch, and her favorite cameraman, Ted Tetzlaff. With Hands Across the Table, she was firmly established, on the earlier basis of Twentieth Century, as the screwball heroine, and she rarely played anything else that is memorable thereafter. It was the forty-fourth of her fifty-seven pictures.

The leading male role was more problematical. Carole’s first choice was Cary Grant, who was committed elsewhere, with Katharine Hepburn, no less. The studio announced two other, improbable, choices, Gene Raymond and Lloyd Nolan, and both Leisen and Carole had wanted the ubiquitous (for Leisen) Ray Milland. Fred MacMurray was finally chosen, with Leisen’s considerable misgivings, though he had made only a handful (for those who have six fingers) of minor films. But one role, that of Hepburn’s aristocratic suitor (or is she the suitor?) in Alice Adams, brough him widely to public attention, and he eventually got solid second billing in Hands Across the Table. He made three more films with Lombard, and became one of Leisen’s most popular leading men.

In hailing Hands Across the Table as likely to be “one of the best-liked entertainments of year,” the New York Times acknowledged the picture’s lineage–“Of all the numerous efforts to recapture the mood of It Happened One Night,” this is easily the most successful.

Notes by Barrie Hayne

You may also like...

-

News

Thank You from TFS!

Toronto Film Society | July 21, 2025Our matinée on Sunday, August 17th – at the blessedly air conditioned Paradise Theatre – will conclude the Toronto Film Society’s 77th season! But take heart, as we’ll be...

Programming

Sunday Afternoons at the Paradise

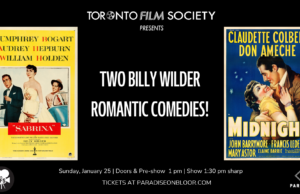

Toronto Film Society | January 25, 2026Join TFS for Season 78’s Sunday Matinée Series generously sponsored by our good friend, author and documentary filmmaker, Mr. Don Hutchison. Please save this date and visit us regularly...

-

Toronto Film Society | January 25, 2026

Toronto Film Society | January 25, 2026

-

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

-

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Donate to Toronto Film Society – We’re now a Registered Charity!

Copyright © 2017 Toronto Film Society.