Kim (1950)

Toronto Film Society presented Kim (1950) on Sunday, March 29, 1981 in a double bill with Mad Wednesday as part of the Season 33 Sunday Afternoon Film Buff Series, Programme 8.

One point of comparison between the two films this afternoon is that a lion appears in each–no; that was The Jungle Book, and as I recall it was a tiger anyway (Though you will see a lion amongst the credits for Kim.

A more serious point of comparison might be that both films were made by artists well past their prime. Preston Sturges was one of the masters of American film comedy–The Lady Eve (1941), Sullivan’s Travels (1941), Hail the Conquering Hero (1944)–who by the late ’40s had lost most of his artistic independence and much of his artistic power, as both the studio editing and the creative fatigue of Mad Wednesday attest. Harold Lloyd was one of the masters of silent comedy, a more distinctively American persona than Chaplin or Keaton, but in this his last film he parodies, intentionally or otherwise, the go-getting, ultimately successful, all-American boy (he was, after all, past fifty) of his best films. And even Howard Hughes has begun to tire of filmmaking.

But the people of Kim, having begun on a lower level, were now, correspondingly past their prime, at a correspondingly lower level of achievement. Victor Saville, the director, had shown great promise in his native England in the 1920s and ’30s. His most successful films had been comedies, or sentimental dramas: Hindle Wakes, The Good Companions, South Riding. When he moved to Hollywood in the ’40s, the sentimental strain became more dominant, both in the films he produced (Goodbye Mr. Chips, Bitter Sweet) and in those he directed (The Green Years, If Winter Comes) {I note in parenthesis the difficulties of discerning method in a producer’s career, for in the ’50s he produced three movies based on Mickey Spillane!] Of the other major figure of Kim, Errol Flynn, it is perhaps only necessary to say that he had passed into his forties, and passed his prime as a vigorously active swashbuckler.

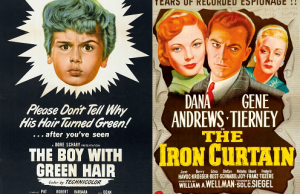

The centre of interest in Kim, in fact, is the relationship between the boy, the orphan who is also a courier and spy, and the old Buddhist Lama, roles which brought together a child star and an experienced character actor. Dean Stockwell was at the height of his career as an actor of sometimes petulant, sometimes mischievous, children when he played Kim. He had been directed by Saville once before, in The Green Years, and he had been social victim (The Boy With Green Hair), insufferable brat (The Secret Garden), regular fella (Stars in My Crown), and even son to Nick and Nora Charles (The Song of the Thin Man). Paul Lukas had played, twenty years before, suave romantic heroes (By Candlelight), that most priggish of detectives, Philo Vance, Jo March’s Professor Baer, the sinister villain of The Lady Vanishes, and then a gallery of Nazis, culminating in his Academy Award performance in Watch on the Rhine. Out of the chemistry of their relationship come two strong, appealing performances.

The years immediately following Kipling’s death in 1936 and seen a number of directors of distinction transposing his work into film: Robert Flaherty (Elephant Boy), Victor Fleming (Captains Courageous), John Ford (Wee Willie Winkie), William Wellman (The Light that Failed), the Kordas (The Jungle Book). As the years passed, directors from far outside the Pantheon turned their attention to him, and made less distinguished pictures: Tay Garnett (Soldiers Three), and eventually Disney (1967) a feture-length cartoon (More recently, a director of distinction, though arguably in his decline, has returned to Kipling in The Man Who Would be King).

But if Kipling himself has declined in popularity in the fifty years since his death, there are obvious reasons for it. Bosley Crowther, reviewing Kim in the New York Times, mused on the “sobering” fact that the setting was the Khyber Pass under the threat of infiltration by Russia and her satellites: a lesson for the times. Since then, of course, we have carried on up the Khyber with Sid James, and in 1981 the Russians are coming through the Pass again. But the perspective has changed, since 1950, and especially since 1910: Kipling’s world, its simple “East is east, and west is west,/And never the twain shall meet”, upset by the intrusion of a third world between the two, now seems infinitely removed from us.

Notes by Barrie Hayne

Dear Madam or Sir:

Thank you for your review of the great 1950 movie “KIM”.

Would you know the name of the closing march played at the closing of the film? I believe it was played at the last scene and during the closing credits. Thank you very much for your reply.

Sincerely,

William Dougherty

Cutchogue, NY

widougher@aol.com