Too Late For Tears (1949)

By Toronto Film Society on July 11, 2017

Toronto Film Society presented Too Late For Tears (1949) on Saturday, November 18, 2023 as part of the Season 76 Virtual Film Buffs Screening Series, Programme 3.

Toronto Film Society presented Too Late For Tears (1949) on Monday, July 10, 2017 in a double bill with Where Danger Lives as part of the Season 70 Summer Series, Programme 1.

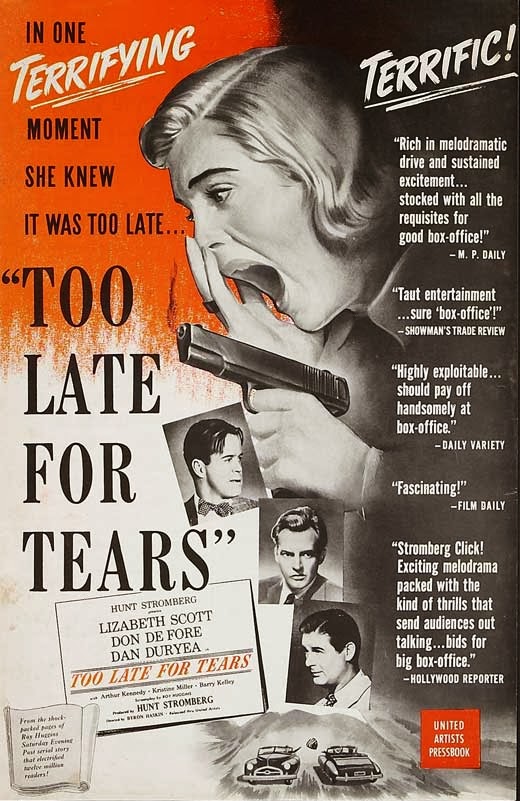

Production and Release: United Artists release of Streamline Pictures, Inc.; Republic Pictures Corp production. Producer: Hunt Stromberg. Director: Byron Haskin. Screenplay: Roy Huggins, based on his novel “Too Late for Tears” (Los Angeles, 1947). Photography: William Mellor. Art Director: Cedric James Sullivan. Set Decorations: John McCarthy, Jr., Charles Thompson. Film Editor: Harry Keller. Music Score: R. Dale Butts. Music Director: Morton Scott. Gowns: Adele Palmer. Sound Recording: Earl Crain, Sr., Howard Wilson. Release Date: July 8, 1949.

Cast: Lizabeth Scott (Jane Palmer), Dan Duryea (Danny Fuller), Arthur Kennedy (Alan Palmer), Don DeFore (Don Blake), Kristine Miller (Kathy Palmer), Barry Kelley (Lt. Breach), Denver Pyle (Young Man at Train Station).

Lizabeth Scott made only about 20 films in her entire career. Because of her blonde hair and blue eyes, she was originally hired by Paramount Pictures for colour films. However, her only colour noir was the 1974 Desert Fury with John Hodiak playing a gangster hiding out in a small town. Scott’s career really began in 1946, when she played the girlfriend of Van Heflin in Lewis Milestone’s The Strange Love of Martha Ivers, which we will be screening here next Monday evening. Director John Cromwell hired her to play a femme fatale opposite Bogart in Columbia’s 1947 Dead Reckoning, afterwards returning to Paramount to play Burt Lancaster’s girlfriend in 1948s I Walk Alone. It was the only other film noir directed by tonight’s director, Byron Haskin. At United Artists, she played a model engaged in artful deception with Dick Powell in Andre de Toth’s 1948 Pitfall before making Too Late For Tears. In 1950, she played the girlfriend of gambler Charlton Heston in William Dieterle’s Dark City for Paramount. Her noir roles ended with the 1951 film The Racket starring Robert Mitchum and Robert Ryan.

Don DeFore played in scores of motion pictures as a second or third lead with his name usually below the title. Tall and handsome, he appeared in many westerns and was considered a reliable leading man, but not especially heroic. He appeared in several film noirs beginning with tonight’s film followed by Dark City and Forgery both made in 1950.

Dan Duryea was definitely no stranger to film noir. He never signed a contract with any studio, but worked as an independent actor, especially in noir roles as the villain during the 1940s and 1950s. No matter if he was second or third lead in a drama, he was always the most memorable. He began his noir career in the mid-1940s. His early genre credits include musical star Deanna Durbin’s first film noir, 1945s Lady on a Train, Fritz Lang’s 1944 Ministry of Fear and 1945’s Scarlet Street. His other memorable roles were as an amnesiac piano player in 1946s Black Angel; as a double-crossed proprietor of a nightclub in 1949s Criss Cross; as a thief trying to kill Dorothy Lamour in 1949s Manhandled; as a gang leader who tried to reclaim his girlfriend and $200,000 of stolen money in Mexico in 1950’s One Way Street; and as a wounded bank robber in both 1956’s Storm Fear and 1957s The Burglar.

Writer Roy Huggins was the creator of the long-running television series The Fugitive, also writing 23 of its episodes. He also wrote for the big screen in the 50s and 60s, although he barely ventured into film noir, writing only the screenplay for tonight’s film which was drawn from a series first published in The Saturday Evening Post, and 1954s Pushover starring Fred MacMurray, Kim Novak and Dorothy Malone. Huggins also wrote for the television series Maverick, The Virginian, 77 Sunset Strip and Run for Your Life.

Sourced from Houses of Noir: Dark Visions from Thirteen Film Studios by Ronald Schwartz (2014)

Introduction by Caren Feldman

“It was a pleasing picture,” said director Byron Haskin on Too Late for Tears in a 1983 interview of a Directors Guild of America oral history project. “I put every effort I possibly could into the cheap little story by Roy Huggins, with a fairly good cast—the amiable Liz Scott, and Dan Duryea. I loved him—he had great style and gave a dimension it’s difficult to describe, let alone direct. So much more than you ever asked for. He’s one of the pleasures of my early directing career.” Indeed, Dan Duryea is also a pleasure for fans of film-noir, with his blond mane and oily, scheming, and deliciously evil characters popping up over and over again in films of the style. As for Lizabeth Scott, she turns in one of film-noir’s most entertaining bad-girl performances, whose greed will let her stop at nothing to keep the dough—even, of course, murder.

Released by United Artists, Too Late for Tears was produced by Hunt Stromberg, who had once been a prominent in-house producer at MGM but who, in recent years, had been making films independently. For this production, Stromberg worked hard to cobble together cast, crew, financing, and even the property itself from various sources. The screenplay was by a relative newcomer, Roy Huggins, adapted from his own Saturday Evening Post serial. (Years later, Huggins would create the TV shows Maverick and The Fugitive, among many other famous credits.) Stromberg acquired the script from another independent producer, Milton Sperling, then made a deal with yet a third, Hal Wallis, to borrow Haskin, Scott, Arthur Kennedy, Kristine Miller, and supporting actor Don DeFore, all of whom were under contract to Wallis. Meanwhile, Stromberg made an unusual deal with Republic Pictures to provide studio facilities and financing. Republic was effectively producing the film for United Artists to release, even though Republic was a distributor, itself. For its services, Republic participated heavily in profit-sharing.

The resulting movie did well at the box office and drew overall positive reviews. Variety declared the “picture suffers from a contrived plot which never entirely rings true and from over-writing, but [the] basic idea is so novel and intriguing to pop imagination that it counterbalances all defects and maintains audience interest.” The New York Times said, “This yarn about a cash-hungry dame who doesn’t let men or conscience stand in her way is an adult and generally suspenseful adventure…. Scott is a taut, seductive, husky-voiced schemer who is fascinatingly convincing in a completely unsympathetic role. Dan Duryea adds another excellent and familiar portrait to his gallery of tough mugs.”

Half a century after its release, Too Late for Tears was on the verge of becoming a lost film. It had fallen into the public domain, which meant that existing prints were in terrible shape and fly-by-night home video distributors had flooded the market with awful-looking copies. It also meant, as UCLA Film & Television Archive preservationist Steve MacQueen put it, that there was “no one with a vested interest in putting resources into saving such a film—no one except organizations like the Film Noir Foundation and film archives.” Film Noir Foundation president Eddie Muller spent five years as the driving force to restore the film, which he described as “the best unknown American film noir of the classic era.” Muller discovered that the original negative had long since been lost, so he set about searching for the best copies of the film still out there that the UCLA restoration team could use as sources. In the end, after some false leads—and in an echo of how producer Stromberg had cobbled together the film itself—Muller found three viable source materials: a 1949 nitrate, French composite dupe negative; a 1955 reissue print that was already decomposing; and a 16mm television print. Finding these sources was tricky in and of itself, as the French negative was catalogued under the title La Tigresse and the 1955 print was listed under an alternate title, Killer Bait. But UCLA was able to use the best pieces of all these sources to create a fresh negative from which new 35mm prints could be struck. The restoration was funded by the Film Noir Foundation with additional funding by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association Charitable Trust.

Notes by Peter Poles

The Canadian Connection

Too Late for Tears has two Canadian connections! Two-time Academy Award nominated set decorator Charles S. Thompson was born on August 28, 1908 in Canada. Unfortunately, that’s as specific as we can get. His first Hollywood credit is 1943’s Carson City Cyclone, one of 20 films he worked on that year. He’s best known for The Quiet Man (1952) and A Patch of Blue (1965). He worked consistently until 1972, wrapping up with the Clint Eastwood film Joe Kidd and a made-for-TV film, The Return of Charlie Chan.

Actor John Butler is the other Canadian connection. Born in Canada in 1884 (again, nothing more specific is available), he didn’t begin his film career until the age of 42, but he made 140 appearances between 1936 and 1953, mostly in small roles, often uncredited. His films include The Farmer Takes a Wife, The Pride of St. Louis, and Strangers on a Train.

You may also like...

-

News

Frances Blau

Toronto Film Society | February 27, 2024On Monday, February 26th, 2024, Toronto Film Society lost longtime friend, supporter, and board member Frances Blau. Known for her sense of humour, her love of film, her generosity,...

-

Special Events

Arsenic and Old Lace (1944) at the Paradise Theatre

Toronto Film Society | April 21, 2024Toronto Film Society presents Arsenic and Old Lace (1944) at the Paradise Theatre on Sunday, May 5, 2024 at 2:30 p.m. Screwball comedy meets the macabre in one of...

Programming

Virtual Saturday Night at the Movies

Toronto Film Society | April 11, 2024Toronto Film Society is back in the theatre! However, we’re still pleased to continue to bring you films straight to your home! Beginning Season 73 until now we have...

4-

Toronto Film Society | April 21, 2024

Toronto Film Society | April 21, 2024

-

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

-

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Donate to Toronto Film Society – We’re now a Registered Charity!

-

Copyright © 2017 Toronto Film Society.

Leave a Reply