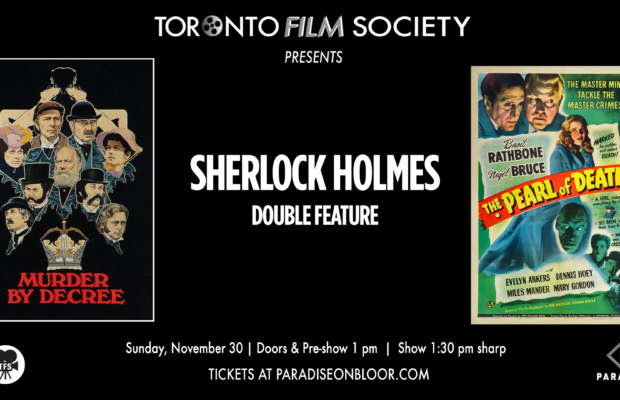

Murder by Decree (1979) and The Pearl of Death (1944)

Toronto Film Society presented Murder by Decree (1979) on Sunday, November 30, 2025 in a double bill with The Pearl of Death (1944) as part of the Season 78 Series, Programme 2.

Production Companies: CFDC, Famous Players. Distribution: Embassy Pictures Corporation. Producers: Bob Clark & René Dupont. Director: Bob Clark. Screenplay: John Hopkins, based on The Ripper File by John Lloyd & Elwyn Jones, and with characters from The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Cinematographer: Reginald H. Morris. Editor: Stan Cole. Production Design: Harry Pottle. Composers: Paul Zaza & Carl Zittrer. Released: February 1st, 1979 (The University Theatre, Toronto, Canada). Running time: 124 minutes.

Cast: Christopher Plummer (Sherlock Holmes), James Mason (Dr. John Watson), David Hemmings (Inspector Foxborough), Susan Clark (Mary Kelly), Frank Finlay (Inspector Lestrade), Anthony Quayle (Sir Charles Warren), Donald Sutherland (Robert Lees), Geneviève Bujold (Annie Crook), John Gielgud (Lord Salisbury), Peter Jonfield (William Slade), Roy Lansford (Sir Thomas Spivey), Rob Pember (Makins).

As any story of a manic detective should go, Murder by Decree finds Bob Clark in the trenches of directing a mad-house account of one of the most dangerous criminals of all time, Jack the Ripper, being sought out by none other than the great Sherlock Holmes.

Inspired by versions of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s characters, and drawing from accounts of Jack the Ripper, the film follows Holmes and Watson as they dig into a case that leads them through stagecoaches into the night, racing around streets into asylums, run-ins with police, inspectors and mediums and into a territory beyond what they as simple men can pursue.

Christopher Plummer and James Mason as Sherlock Holmes and his unique partner Dr. Watson is a strange but inviting pair whose relationship, although meant to be serious due to the nature of their career and status of the crime, brims with hilarity, resembling less of two intelligent detectives and more of way-too-close, bickering roommates in a darkly-tinged sitcom. The characters they meet along the way, Inspector Foxborough, Mary Kelly, and Robert Lees, breathe life into the film’s Victorian-era dramatics, making this thriller over-the-top in a solemn way.

Sherlock Holmes and Dr. John Watson – a duo with interesting chemistry that feels like it isn’t there, but with something that pulls them together. Their dialogues are disjointed and though they consistently confuse one another in their methods, somehow, some way, their perspectives and personalities mesh to create one mind and one detective working the case from opposite sides. Their conversations in the study or in their rides in coaches convey a sense of closeness and dissonance that comes from a lifelong partnership and understanding – the kind that allows for comedic relief in an otherwise dreary profession.

The political looms over the main arch of the narrative. No one is to be trusted in the pursuit of a socially illegal child. This is where the water gets muddy. The blending of politics and unspoken societal law among the people, the status quo, envelopes all who cross paths with Jack the Ripper. We see this in Watson’s run-ins with underground night-workers, on the docks with a man hidden, the group of men that visit them at their house at night and the wariness of Holmes and Watson in their engagement of the crimes, the medium Robert Lees, whose recount of his experiences mimic that of the silent way we must cope with terror. We see this again with Mary Kelly and her waterfall of emotions and with Annie Crook, whose silence is deafening even before she explodes. We are led to an end, but a true end remains forever out of reach, creating an intangible mystery – not of a ghost or a paranormal or extraterrestrial kind, but of the nature of created culture and belief in social groups and powerful political underground parties. Holmes’ monologue to the prime minister says it all.

Trust and truth are a common theme of mysteries, and this is not an exception to the rule. The adventures of Sherlock Holmes and his trusted partner, Dr. Watson, are known to rely heavily on mysterious characters, and circumstances that complicate the cases they follow. Trust and truth are two difficult things to put together. Who can you trust when everyone involved could be a suspect? How do you solve a case where the murderer is leading you to him and away from him at the same time?

The film’s Canadian connection runs quite deep:

The film was the recipient of 5 Genie awards out of 8 nominations in 1980, and was the highest grossing film in Canada at the time with 1.9 million in revenue.

CFDC, currently known as Telefilm, and Famous Players, now Cineplex Cinemas, produced the film and are and were two prominent corporations in the production and distribution of feature films within Canada.

The film premiered in Toronto at The University Theatre, which was a single screen theatre on Bloor Street West.

Christopher Plummer (born Arthur Christopher Orme Plummer in Toronto, Ontario, December 13th, 1929) was an acclaimed actor for his roles on the stage and on screen. His roles spanned several genres, decades and generations, notably in The Sound of Music (1965) as Georg Von Trapp. His contributions to cinema in various iconic roles are countless. He was appointed to the Order of Canada and passed away in 2021.

Susan Clark (born Nora Golding in Sarnia, Ontario, March 8th, 1943) is an actress with a great roster of films as co-star alongside several acclaimed actors such as Gene Hackman, Dean Martin and Robert Redford. In 1975 she won an Emmy for the TV film Babe, as Babe Didrikson Zaharias. She retired in 2007.

Geneviève Bujold (born in Montreal, Quebec, July 1st, 1942) is a critically acclaimed actress known for her extensive collection of roles in varying genres of film and television. She received an Academy Award nomination for her role as Anne in the film Anne of the Thousand Days in 1969, and was in popular films such as Dead Ringers (1988). In 1994, she was slated to play Captain Nicole Janeway on the television series Star Trek: Voyager, but left the role after two episodes. Her final role was in 2018.

Donald Sutherland (born Donald McNichol Sutherland in St. Johns, New Brunswick, July 17th, 1935) was a prolific and prominent actor and presence in the entertainment industry who received numerous awards and accolades, including an appointment to the Order of Canada. His career spans many genres and features critically acclaimed films, such as, but not limited to: M*A*S*H (1970), Klute (1971), Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978) and most recently in the acclaimed Hunger Games franchise (2012-2015). He passed away in 2024.

Notes by Lorenza De Benedictis

Production Company: Universal. Producer & Director: Roy William Neill. Screenplay: Bertram Millhauser, based on a story by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, “The Adventure of the Six Napoleons.” Cinematography: Virgil Miller. Art Director: John B. Goodman, Martin Obzina. Film Editor: Ray Snyder. Music: Paul Sawtell. Set Decoration: Russell A. Gausman, E.R. Robinson. Costumes: Vera West. Release Date: August 1, 1944. Running time: 69 minutes.

Cast: Basil Rathbone (Sherlock Holmes), Nigel Bruce (Doctor Watson), Dennis Hoey (Lestrade), Evelyn Ankers (Naomi Drake), Miles Mander (Giles Conover), Ian Wolfe (Amos Hodder), Charles Francis (Digby), Holmes Herbert (James Goodram), Richard Nugent (Bates), Mary Gordon (Mrs. Hudson), Rondo Hatton (“The Creeper”), Billy Bevan (Constable).

The Pearl of Death is one of many Sherlock Holmes films starring Basil Rathbone – the actor who defines Sherlock for so many of us – and Nigel Bruce as his foil, Dr Watson. It’s also one of many directed by Roy William Neill, a little spoken of but highly prolific director of B movies. He directed over a hundred films in his thirty-year career, including eleven Sherlock Holmes films with Rathbone, as well as such titles as Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man. In Sherlock Holmes on Screen, Alan Barnes writes that The Pearl of Death is “positioned almost exactly between the pulp adventure of The Spider Woman and the horror mechanics of The Scarlet Claw.” Despite working entirely at “B” level, Neill was “a real artist,” according to veteran sound recordist and director Edward Bends, who noted “his care in making camera placements inevitably caused him to fall behind schedule.”

In adapting Arthur Conan Doyle’s story “The Adventure of the Six Napoleons,” screenwriter Bertram Millhauser added a patriotic speech, as was typical of the wartime era, in which Holmes “likened the greed of men for pearls to the greed for world domination.” To appeal to audiences looking for thrills, he also added a couple of new characters to fit the classic B tropes.

Evelyn Ankers – aka “Queen of the Bs” – brings her vocal talents to the Irene Adler-esque character of Naomi Drake. Ankers appeared in over fifty films, cast mainly for her authentic-sounding blood-curdling scream. She wrote in 1978 of meeting a woman extra on set who had worked for many years dubbing screams for hundreds of actresses including the original scream queen, Fay Wray.

With Evelyn Ankers on set though, she was out of a job. In addition to her scream, the role of Drake shows off Ankers’ ability to use a variety of accents, from Cockney to Irish to posh. Born in England, she moved to Hollywood and had to learn to speak convincingly American. Her career took her back and forth between US and UK roles, and she often took it upon herself to correct scripts set in England.

“The script writer, unless he was English himself, wouldn’t know the many different idioms, slang, and provincial sayings… to give the part credibility, I had to add all these things myself.” When The Pearl of Death was shot, she had just finished fourteen films playing American. She was concerned about nailing all of the accents that Drake puts on, but director Neill assured her, “since the girl was supposed to be faking it anyway it didn’t have to be letter perfect.”

The Pearl of Death was her second Sherlock Holmes (after Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror, 1942) and she loved working with “Rasil Bathbone” as she called him. It was “always fun working with” him.

Another classic B trope brought in to juice up the script was the character of “The Creeper” as played by Rondo Hatton. Hatton had been voted “Handsomest Boy in his class his senior year” at Hillsborough High School in 1913, but by the 1920s he began showing symptoms of acromegaly—a disorder of the pituitary gland—and his “head, face, hands and feet became increasing large and deformed.” As the disease progressed, his career as a journalist faltered, but when he visited the set of Hell Harbour (1930) for a story, director Henry King noticed him and thought he’d make a great villain.

Hatton played a number of bit parts, roles like “Ugly Man,” “The Leper,” and “Convict Sitting on Floor.” But it was his turn as “The Hoxton Creeper” in The Pearl of Death that really kickstarted his career. It “endeared him to horror fans and Universal, which quickly used him in similar parts.” Known as “the only film star to play monsters without make-up,” descriptions of his appearance by film writers range from graphic to downright cruel. “Hulking, hideous,” “King Kong-like”… in The Golden Age of B Movies, Doug McLelland goes so far as to suggest that Neill’s camera angles and “suggested horror” were used because he “was simply worried that Hatton’s grotesqueness might be too much for some audiences.” Hatton died of complications related to acromegaly less than two years after The Pearl of Death was released. He reprised the role of “The Creeper” in two films released posthumously, one of which was used as a model for the statuette handed out at the annual Rondo Hatton Classic Horror Awards.

Rathbone eventually tired of cranking out Sherlock after Sherlock, exiting the franchise after fourteen films, but it “remains one of the more sturdy film series, B or otherwise, mystery or not,” writes Dan Miller in B Movies. Universal’s Howard S. Benedict, executive producer of the films, “lists The Pearl of Death as his personal favourite in the series.” Not bad for a film made in just over three weeks for a budget of under $200,000.

Notes by Jennifer Beer

Sunday Afternoons at the Paradise

Join TFS for Season 78’s Sunday Matinée Series generously sponsored by our good friend, author and documentary filmmaker, Mr. Don Hutchison. Please save these dates and visit us regularly...