Reaching for the Moon (1930)

A Masculine “What a Widow” with a box office career before it of moderate proportions. The Fairbanks and Daniels names should attend to that on the basis that the picture, itself, is just fair.

If there’s as much coin in this one as they say there is, and the report is that the negative cost will charge off around seven figures, “Reaching for the Moon” has got a battle on its hands to get back such an outlay. And that it’s an expensive picture is obvious from the screen. Sets are imposing and lavish. Add to that the time it took to get this film under way, also the amount which must have gone to the picture’s two leads, and it’s not mental telepathy to think that the cost sheet on “Moon” can be no small matter.

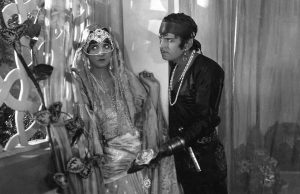

For entertainment it’s not a typical Fairbanks yarn. It’s more than possible that too many cooks twisted this story until it finally unreels as an unimpressive theme. The dialog occasionally sparkles but does not sustain its pace. A danger here is that many film patrons will even muff the comedy verbiage between Fairbanks and Horton. To counteract that, however, is the Fairbanks appeal to the women and a blond Bebe Daniels who will hold retina attention. She does well enough with a not particularly sympathetic part. Fairbanks looks in splendid physical shape in this picture, doesn’t have to fear a microphone, and if given a suitable script definitely reminds that he can continue to be a box office factor.

Which induces a query as to why this athletic star should dodge “Hawthorne, U.S.A.” as a picture. That’s a show he did back in 1912 at the Astor; a typical Fairbanks script which would keep him in modern dress, a point the exploitation on “Moon” is stressing. Fairbanks doesn’t typify the modern business man on the screen. Never has. But he does spell rollicking romance to fans and the odds are that Douglas, Sr., with a Rex Beach background would be well worth a bet in sound.

Here he’s a big Wall Street operator whose dizzy routine is interrupted by Miss Daniels who maneuvers her way into his office on a wager. Intrigued, Fairbanks drops everything to rush aboard the transatlantic liner she’s taking after she omits keeping a dinner appointment with him. Remainder of the footage all takes place on the boat with Claude Allister as the silly ass British fiancé of Miss Daniels who is supposedly a famed aviatrix going abroad with a group of femme flyers for some obscure purpose. Further continuity includes the market crash, which Fairbanks gets by phone to the boat, and ends in a wedding back in New York after he has been spurred to a retrieve try by the girl.

Goulding, in directing, has gone deep into the trunk to pry forth the old burlesque bit of a liquid concoction which makes the timid bold. This sequence is permitted to run into overemphasis, yet develops into the strongest laugh footage in any of the reels. It’s universally understandable hoke will probably go a long way to save the feature in a vast majority of its play dates. It has both Miss Daniels and Allister innocently sipping of the cup, for an immediate personality change, and winds up as Fairbanks, a teetotaler, takes two or three gulps to go wild in a shipboard chase with rings in a string of stewards. Another comedy scene is bodily out of the past, in having Horton, as the valet, teaching his master the art of wooing. Regardless of its merit, and the double entendre dialog between the two men does much to assuage for the mechanics, this revival of old bits throws the weakness of the story into sharp relief.

None of the Berlin songs is left other than a chorus of hot number apparently named “Lower Than Lowdown.” Tune suddenly breaks into the running in the ship’s bar when Bing Crosby, of the Whiteman Rhythm Boys, gives it a strong start for just a chorus which, in turn, is ably picked up by Miss Daniels, also for merely a chorus, and then an exterior shot to the deck where June MacCloy sends the lyric and melody for a gallop of half a chorus. That cleans up all the vocalizing in the film despite the fact that the title song is spasmodically included as a musical background. Originally, Berlin had five ditties penciled into this picture.

Other than Fairbanks, Miss Daniels and Horton support cast members are given little leeway. Horton is excellent and invaluable in holding the picture together. Allister does his theatric Britisher capably while June MacCloy may catch passing attention on her appearance. It is also evident that this girl knows how to warble a torrid tune, to be expected in that she’s supposed to have hopped from cabaret to pictures. Miss Eddy does well with a very small part.

The Fairbanks and Daniels names figure to give this release a marquee head start while the resultant viewing will generally class it as but fair and light entertainment. Where expectations are high it will disappoint.

It seems that they’ve tried to do the same with Fairbanks as they did with Miss Swanson in her last release. It’s a long way from the ideal solution but leaves a loophole for the male star to crash through in a future talker of the type they expect and will definitely go for from him.

VARIETY, Sid.,January 7, 1931

In terms of billing at least, tonight’s films (“Reaching for the Moon” 1917 and 1931) provide a well-balanced program. They also show us Doug sr. near the beginning of his career, and near the end—in both cases doing the kind of things that so many of us feel he did best. Film history may recall Doug best for his handful of elaborate swashbucklers made in the 20’s, many of which were certainly diverting, and all of which certainly had the fringe values of spectacle and huge-scale production qualities. But to most of us, “Doug” conjures up the image of the zippy, sophisticated modern comedies, of which tonight’s two films are fine and thoroughly entertaining examples. Apart from the repetition of the title, there is no connection between the two films, and the one is not a remake of the other.

When it first appears, “Reaching for the Moon” disappointed the public. Made far more as a musical, it was reshaped and cut when the musical vogue appeared to be over. Almost all of the songs disappeared, and the title number remains only as theme music, and as the tall end of a dance number. Then too, with Fairbanks’ big swashbucklers so fresh in the memory, its limited acrobatics seemed tame. Today however, when we can look back on the very early 30’s with new perspective (and realize how fresh and cinematic this film is compared with so many of its contemporaries), and too when we judge Fairbanks by his whole career and not just by his specials of the 20’s, it takes on a whole new set of values.

For one thing, Doug is back in his old stride again. He has all the zip and pep that he had in his early modern comedies; this “Reaching for the Moon” is a logical extension of the old, the passage of time being emphasized only by the fact that Doug is now a self-made millionaire instead of a super-optimist on the way to becoming one. Even his voice seems just right for ths character—it may not have the Colman ring that one would expect of a talkie D’Artagnan, but it has the perfect youthful ebullience of the millionaire that never grew up! The restrained acrobatics disappoint, true, but only because they’re not really needed. Doug gives the film all the dynamics it needs in voice and gesture; the odd leaps and stunts are merely added punctuation. One would like to see Doug the athlete at his full powers or not at all, but this is a small quibble when the film has so much else to offer; quite apart from the aplomb of Doug and the beauty of Bebe Daniels. There’s Edward Everett Horton in one of his funniest roles, getting away with blue jokes and outrageous innuendoes right and left. There’s a youthful Bing Crosby in a spirited number, and some beautiful but mannish girls who add to the dominace of off-beat sexual humor which is often as blatant as that in “What’s New Pussycat”, but is far funnier and more tasteful. (One double-entendre is so outrageous one still wonders if it was intended that way!) However, the homosexual humor is tasteful and funny, as it often was in that period; one has only to look at such cotemporary comedies as “Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter Brother” to realize the lack of taste—and humor—in much of such comedy today. And far from least, there are the spacious, modernistic and art-deco designs/sets by William Cameron Menzies, (five years before he made “Things to Come”), whose bizarre penthouses, ship interiors and non-moving seascapes add a deliberate touch of determined unreality that offsets the then very topical grim reality of the depression. Suicide and financial ruin are plot ingredients of “Reaching for the Moon”, but Doug and Mr. Menzies prevent your ever taking them too seriously. But they do ask you to take the sentiment seriously. Audiences at the film’s last exposure (some ten years ago at the 5th Avenue Cinema) did alas laugh at some of the film’s honest sentiment—but Doug’s own on-screen remark “You’re laughing at me—that’s cruel and despicable!” soon put them in their places, as it will anyone here tonight so heartless as to laugh in the wrong place.

Many Fairbanks fanciers tend to look down their noses at this “Reaching for the Moon”, and prefer to pretend it doesn’t exist. I’m not one of them. If some inhuman destiny one day decreed that all but six Fairbanks films would have to be consumed by flames, this is certainly one I’d save at the expense of a “Robin Hood” or a “Don Q”.

WILLIAM K. EVERSON, 1965/1967/1976

REACHING FOR THE MOON, United Artists production and release, written and directed by Edmund Goulding with additional dialog by Elsie Janis, Ray Janee, cameraman, Oscar Logerstrom, sound, with music by Irving Berlin.

Buffoonery de luxe, a soupcon of musical comedy plot, a hybrid conception of French farce, streaks of sentiment, acrobatics and clever modernistic settings are to e found in “Reaching for the Moon,” the audible picture featuring Douglas Fairbanks and Bebe Daniels, which was launched last night at the Criterion before a brilliant audience. It is an incredible mixture wherein Mr. Fairbanks appears on the screen in modern clothes for the first time in several years. But its harum-scarum action was received with hearty laughter, particularly those incidents devoted to the curious effects of a cocktail known as “Angel’s Breath,” which is imbibed by Mr. Fairbanks as Larry Day, by Miss Daniels as Vivian Benton, by Edward Everett Horton as a valet, and others.

This peculiar concoction causes Larry Day, a man of millions, to leap into the air, climb up walls and do other stunts that demand no mean agility. And Mr. Fairbanks in this film is just as active as he was in the early days of pictures.

Most of the action takes place on board an ultra-modern French liner, called L’Amerique, but before these ship scenes are beheld one has the opportunity of watching Mr. Day, a man of much money and a dozen or more telephones, who, one is asked to believe, has been so wrapped up in his financial activities that he is strangely bashful in approaching women.

After he meets Vivian he is so entranced by her beauty and her melodious voice that he takes advice from his valet, Roger (Mr. Horton), as to how he should approach the girl when she comes to his home. A man who had spent all his life on a desert island where there were no females of the species could not be more awkward than Mr. Day. When all the preparations for Vivian’s reception are made she decides not to keep her appointment, but accompanies several of her girl friends aboard L’Amerique to go to Europe. Ten minutes before the steamship is due to leave Larry Day learns by means of the useful telephone that she is making fun of him. His request that the ship’s departure be delayed is tantamount to an order, and soon the wild Mr. Day dashes on the liner, calls for a steward, puts on the man’s jacket and invades Vivian’s stateroom.

Celerity is the way of all things in this picture. In keeping up the speed, the nonsense, the jesting and the effect of the “Angel’s Breath” cocktail, which out to be called a “Double Soixante-quinze,” Edmund Goulding has done his task without losing any time until he comes to the inevitable misunderstanding between Vivian and Larry.

While Larry is seeking to find a way to Vivian’s heart, word is received by telephone from New York, when l’Amerique is in mid-ocean, that his millions have been swallowed up in a financial debacle. When this millionaire is in love he doesn’t care to listen to anything about money. But when Larry learns that Vivian loves him, and she tells him so, so one must believe it, his lack of millions means little. What’s more, Vivian is a girl of fabulous wealth and she is confident that what Larry was once he can be again. In other words, there’s no holding him down.

This picture was written as well as directed by Mr. Goulding. The story, according to the program, is based on one by Irving Berlin, who also contributed the music. There is only one song, which is called “High Up and Low Down.”

Mr. Fairbanks occasionally looks as if he aspired to be the great lover in film comedies, for he is not satisfied with changing his clothes frequently, appearing in outing or lounge suits, a swallow tail suit, a dinner jacket, a dressing gown, but also stripped to the waist. He is quite all right as the comedian, but even when he tells Vivian that he as Larry never thought of going down on his knees to any other woman but his mother until he met the girl in the case, one is hardly convinced that he means what he says.

Miss Daniels gives a good performance. Vivian, however, is not presumed to be rational all the time and she has her most hectic of moments after she sips the potent “Angel’s Breath.” It is then that she makes her fiancé, Sir Horace Partington Chelmsford, tremble and also many other who are in her way. Fortunately this drink wears off after a while and those who have imbibed it eventually return to comparative sanity.

Claude Allister furnishes some of the fun as Sir Horace. Mr. Horton also handles what is allotted to him with no little sureness.

NEW YORK TIMES, by Mordaunt Hall, December 30, 1930

Leave a Reply