The Cat and the Canary (1927)

Toronto Film Society presented The Cat and the Canary (1927) on Monday, April 17, 1967 as part of the Season 19 Monday Evening Silent Film Series, Programme 6.

(Main Auditorium, UNITARIAN CHURCH, 174 St. Clair West)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Programme No. 6

Monday April 17, 1967

8:15 pm

1916: (Title to be announced)

1927: The Cat and the Canary

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

With the exception of Cops (1922), all our films this season–features and shorts alike–have been made in either 1916, 1920, or 1927. It is fitting therefore that our final program of the season, featuring a film made in the latest of those three years, should open with a short (you could call it a documentary if you like) which gives a contemporary glimpse into the way films were made in the earliest of those years, 1916. Films were not necessarily better in 1927 (we feel sure there will be no argument if we state flatly that Intolerance is a greater film than The Cat and the Canary), but in the eleven years that separate them the advances in style and in the technique of screen narration, and truly astonishing. (Has a comparable advance been made between 1956 and 1967?)

Studio conditions, however, must have been approximately the same throughout the whole of the silent period–not counting the earliest days when even interiors were lit by sunlight instead of artificial light. Until talkies required sound-proof sets, the Hollywood studios continued to make umpteen films simultaneously on adjacent open “stages”–except in the case of certain “temperamental” stars who were in a position to demand that their sets be curtained off to avoid the distraction of extraneous activities and casual passers-by.

The short that we hope to show tonight should give you a very instructive view of Hollywood film-making in A.D.1916.

* * *

The Cat and the Canary

Universal-Jewel, 1927

From the play by John Willard

Adaptation by Robert F Hill and Alfred Cohn

Directed by Paul Leni

Sets by Charles D Hall

Copyright by Universal Pictures Corporation, March 31, 1927

8 reels

CAST:

Annabelle West…………….Laura La Plante

Paul Jones………………….Creighton Hale

Charles Wilder………………Forrest Stanley

Lawyer Crosby……………..Tully Marshall

Cecily………………………..Gertrude Astor

Harry…………………………Arthur Edmund Carewe

Hendricks……………………George Siegmann

Aunt Susan………………….Flora Finch

The doctor…………………..Lucien Littlefield

Mammy Pleasant…………..Martha Mattox

The milkman………………..Joe Murphy

The taxi driver………………Billie Engel

This film is a screen version of the stage play of the same name by John Willard (1885-1952) which opened at the National Theatre in New York on February 7, 1922, with a cast headed by Henry Hull and Florence Eldridge, and ran for 349 performances. In October of the same year it also began a long run at the Shaftsbury Theatre in London. The play is still listed in the Samuel French catalogue; and the BBC presented a television production of it as recently as May 9, 1959.

There have been at least three screen versions of the play: the silent film we are to see tonight; a 1930 talkie remake called The Cat Creeps (likewise by Universal; directed by Rupert Julian); and the 1939 Paramount film with Bob Hope, Paulette Goddard, Douglass Montgomery, Gale Sondergaard, Elizabeth Patterson and Nydia Westman. (Quiz for film buffs: figure out–if you don’t actually remember–which of these players played which role).

Photoplay Magazine for July 1927 selected The Cat and the Canary as one of the seven “Best Pictures of the Month” (out of a possible 28; for the others, see page 6). Here is their review, reprinted in its entirety:

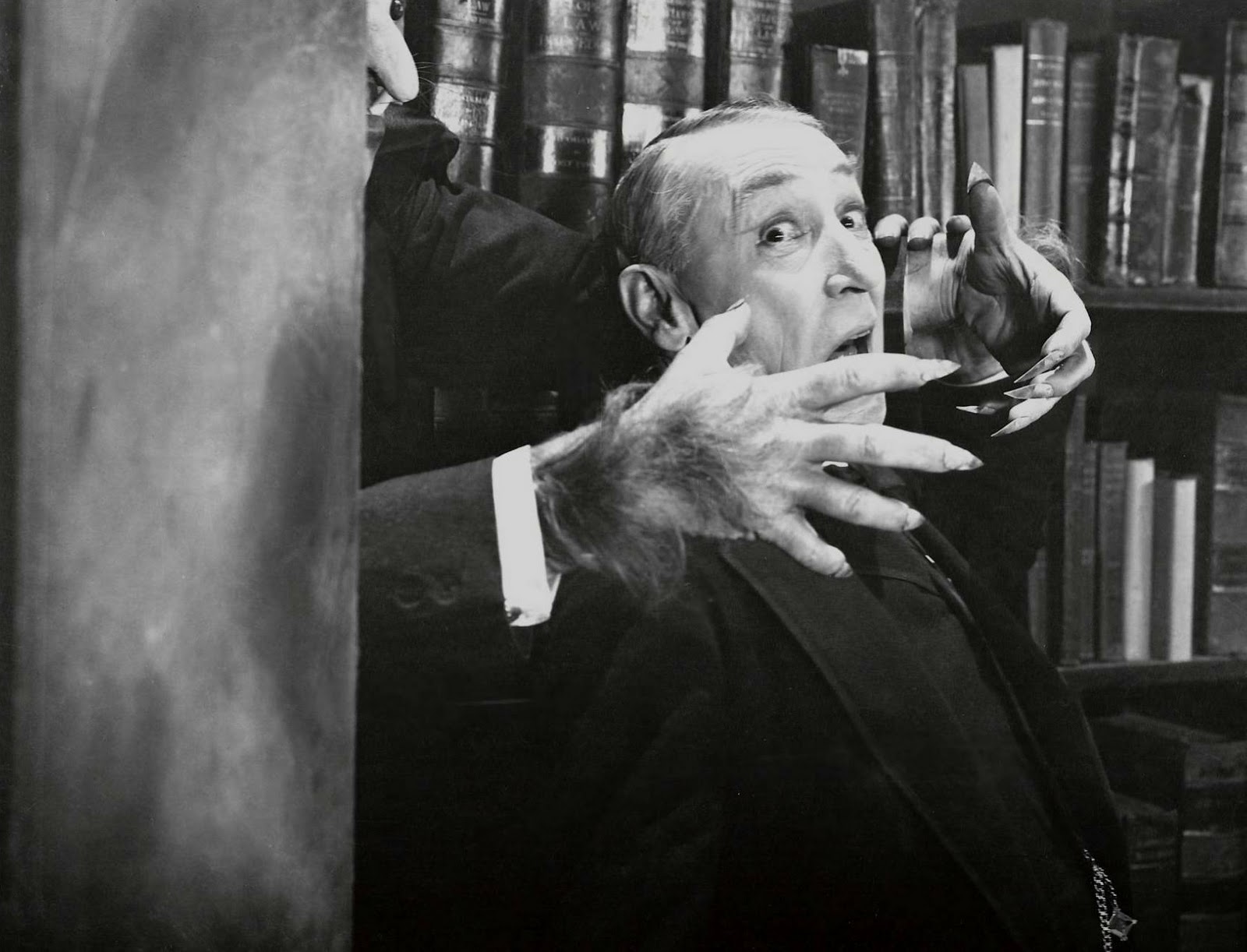

Here is a corking melodrama. Mysterious fingers reach out of mouldy draperies to steal jewels and trick bookcases swallow up unsuspecting victims.

It all happens in an old, shabby mansion once occupied by the eccentric recluse, Cyrus West. It is exactly twenty years from the date of his death to the second and his will is being read to his anxious relatives while a storm beats upon the broken windows.

It develops that Annabelle West, his pretty niece, is the heiress, provided that she sleeps in his dusty cobwebby bedroom (SIC; SEE FOOTNOTE 1) and is able to prove her sanity next morning. Annabelle’s sanity gets a stiff test, we’ll tell the world, between disappearances and murders. To help things along an asylum keeper happens in, searching for a runaway maniac.

Of course, there is a guilty person who hopes to inherit the estate. This person is the instigator of the dire doings.

The Cat and the Canary is adroitly directed by Paul Leni, the German who made The Three Waxworks. He uses trick angles galore, but they all help the atmosphere of mystery and murder. Leni is a director to be reckoned with.

The Cat and the Canary, which, by the way, is based on John Willard’s Broadway mystery shocker, has an excellent cast. Laura La Plante is the blonde heroine, Annabelle. Creighton Hale overdoes the nervous comedy hero, Paul Jones. Indeed, the comedy is the one weak element in The Cat and the Canary. Well done bits are contributed by Lucien Littlefield and Martha Mattox.

FOOTNOTE 1: Surely this is wrong. The insanity clause is there all right, but unless our memory is playing tricks, sleeping in the bedroom was not a condition of the will.

FOOTNOTE 2: Social historians will note the use of the contemporary slang expression “I’ll tell the world!–meaning “That’s for sure!” or as they also used to say back in 1927: “And how!”

Joe Franklin includes The Cat and the Canary in his Classics of the Silent Screen as one of the “Fifty Great Films”; but those of you who are looking forward to reliving the thrill you got when you were young–or those of you who have heard from your elders what a super-thriller this was–should take note of Franklin’s caveat:

It must be admitted that the film doesn’t survive the years without creaking a little, but this is not so much due to defects in the film itself as to the fact that it was really a blueprint of its own species. The format has now been repeated so many times since, the sliding panels and clutching hands degenerating through the years into such casual clichés that the original just doesn’t have the same punch it had in 1927. The cards have rather been stacked against this one, but nevertheless it’s still a striking and fascinating mystery thriller.

In short, you’ve got to go along with this film and think yourself back into a day when all the chill-provoking gimmicks were brand-new and had never been seen before. After all, there has to be a first time for everything. Without doing a thesis on it, we can’t say if these gimmicks originated with this film (or more accurately, with Willard’s play); but Photoplay’s review is evidence that in 1927 they at least were not yet shopworn. Today, most of the elements of The Cat and the Canary have become stock comedy devices (Clyde Gilmour is my witness that one of the shock devices of this film was being parodied as long ago as 1941),–but at least they are still around, as witness a recent Monkees episode where some had to sleep in a haunted house all night in order to claim his inheritance.

(In one respect the film is a borrower: the costuming of the doctor is obviously derived from Dr. Caligari, 1919. But if the mysterious housekeeper, Mammy Pleasant, seems to be straight out of Rebecca, you’re looking ahead to 1939).

Here (in part) is the Museum of Modern Art’s program note for The Cat and the Canary:

The director of this film was the late Paul Leni, distinguished German stage-designer and artist, and director of the film Waxworks. He was brought to Hollywood when the German invasion of the film capital was at its height, and this was his first American film. The décor of the Jack-the-Ripper sequence of his Waxworks had been a triumph of craft and economy since its unforgettably macabre effect was contrived entirely with some sheets of painted paper, ingenious lighting and camerawork. Leni apparently was not appointed to design the sets of The Cat and the Canary; those are attributed to Charles D. Hall. In them the then prevalent influence of the German films is to be seen in the exterior set of the mystery house, while the touch of Leni is evident rather in the dramatic lighting of the interiors and particularly in the gothic effect obtained in the long entrance-hall. The oblique camera angles, the scene looking downward on the assembled characters, the shot through the high back of a chair were expected not only of any German director at the time but of directors in Hollywood generally. 1927 was the year of camera angles.

“German angles” they were called. But The Cat and the Canary was an outstanding rather than a routine example of their use. Note Photoplay’s approving comment. Actually, some contemporary critics complained of the rather gimmicky use of them in this film–usual angles for the sake of novelty, they insisted, and singled out the above-mentioned shot through the back of the chair as a particular offender. (Wonder what these gentlemen would have thought of Sid Furie’s The Ipcress File!)

..The acting, like the characterization, is neither here nor there, and while The Cat and the Canary remains one of the best examples of its type of film, it seems a pity that Leni could not have directed something more psychologically profound, more appropriate to his peculiar talent for evoking spiritual rather than physical terror.

Still, The Cat and the Canary and Waxworks are the two films that Leni is best remembered for, so it obviously hasn’t hurt his reputation.

* * *

PAUL LENI was born in Stuttgart on July 8, 1885. He studied at the Berlin University for Creative Arts (Bildende Künste), and was engaged in theatrical work as of 1903 in Berlin and other cities. For some time he was proprietor of a Berlin theatre called Die Gondel. He began working in films in 1910 with the Vitascope Union, but he was known mostly as a designer until he produced Waxworks (1924). Following The Cat and the Canary he directed The Man Who Laughs (with Conrad Veidt) and The Last Warning (with Laura La Plante), then returned to Germany where he died in 1929.

LAURA LA PLANTE was among the more popular female stars of the day, though this film, being a director’s rather than an actors’ film, affords only a few glimpses of the reasons for her well-deserved popularity. She was born November 1, 1904, in St. Louis, Missouri, and started off in films as an extra at the age of 15, in the old Christie comedies. Her first prominent role was in Charles Ray’s The Old Swimming Hole (1921), and soon afterwards Universal put her under contract. She proved a great asset to the company, with her lovely blonde beauty and her lively sense of humor. She appeared mostly in lightweight entertainment films, but also did some serious roles–she played Magnolia in the first screen version (silent) of Show Boat. She continued on into talkies quite successfully, and eventually married and retired. She returned briefly to the screen as Betty Hutton’s mother in Spring Reunion (1959); and we hear that Bill Everson saw her recently in New York and reports that she is as beautiful as ever.

CREIGHTON HALE was born in Cork, but we find him in American movies as early as 1915. He began as an extra in a Theda Bara film, but before the year was over he was Pearl White’s leading man in the serial The Exploits of Elaine, and he seems to have done a lot of work in serials (which were very popular at that period) for the next couple of years. The Silent Series has seen him recently in supporting roles in two 1920 Griffith films: The Idol Dancer and Way Down East. He was never an outstanding actor but he ehld up his end in many a film in the 1920’s. (The glasses were not part of his regular get-up but were assumed for this role–following the precedent of Henry Hull in the Broadway production; perhaps the playwright specifies them).

FORREST STANLEY, like Hale, seems to have entered pictures in 1915, doing “juvenile” roles. He was Marion DAvies’ leading man in When Knighthood was in Flower (1922), but by 1927 we find him in supporting roles such as this.

TULLY MARSHALL was born in California on April 13, 1864. He originally planned to be a civil engineer but went onto the stage instead. He was prominent in films throughout the 1920’s in character roles–mostly villains (e.g., Excuse My Dust).

GERTRUDE ASTOR was born in Ohio. At 5′ 7 1/2″ she was considered too tall to be a star, but she made a comfortable career in numerous supporting roles. She had the comedy “vamp” role in Harry Langdon’s The Strong Man.

The romantic-looking ARTHUR EDMUND CAREWE was born in Trezibond, Armenia, in 1894, and went to the United States when he was ten years old. Studied painting and sculpture before becoming an actor; and was on Broadway for several years before entering films with the old Vitagraph company. He was mostly a free-lance actor, not under contract to any one studio. If you are wondering where you saw him recently, it was probably in The Phantom of the Opera (1925) which the NFT showed this season. Probably his best role was Svengali in the 1923 Trilby.

GEORGE SIEGMANN was born in New York City. He was Silas Lynch, the mulatto leader, in The Birth of a Nation and Cyrus the Persian in Intolerance, and the Russian General in Hotel Imperial (1926), to name only some that you may have seen recently.

FLORA FINCH was born in England and first appeared on the stage there. In the United States she played in a series of comedies withJohn Bunny which were immensely popular before his death in 1915. Later she turned to drama; and she remained in films as a character actress for many years.

LUCIEN LITTLEFIELD was born in San Antonio, Texas. After a stage career he went into films and did quite a bit of work as a character actor.

MARTHA MATTOX. (Sorry; not a shred of information!)

* * *

We said earlier that The Cat and the Canary was listed by Photoplay Magazine in its July 192 issue as one of the seven “Best Pictures of the Month”. For your information and curiosity, the other six were:

Seventh Heaven (which later won the Photoplay Medal – after a polling of its readers – as the Best Picture of 1927)

Captain Salvation (with Lars Hanson and Marceline Day)

Babe Comes Home (with Anna Q. Nilsson and baseball’s Babe Ruth)

Knockout Reilly (Richard Dix and Mary Brian)

Annie Laurie (Lillian Gish, with Norman Kelly and Creighton Hale)

Senorita (Bebe Daniels)

Photoplay’s choice of the Best Performances of the Month:

Norman Kerry in Annie Laurie

Lars Hanson in Captain Salvation

Charles Farrell in Seventh Heaven

Janet Gaynor in Seventh Heaven

Pauline Starke in Captain Salvation

Lillian Gish in Annie Laurie

Babe Ruth in Babe Comes Home

Ernest Torrance in Captain Salvation

Bebe Daniels in Senorita

Other films reviewed that month include Rookies with Karl Dane and George K. Arthur; Children of Divorce with Esther Ralston, Clara Bow, Gary Cooper and Einar Hansen; Special Delivery starring Eddie Cantor; The Understanding Heart with Joan Crawford, Francis X Bushman, Jr., and Carmel Myers; The Claw with Norman Kerry, Claire Windsor and Arthur Edmond Carewe; The Heart Thief with Lya de Putti and Joseph Schildkraut; The Missing Link with Syd Chaplin; Rin-Tin-Tin in Tracked by the Police; Laura La Plante in The Love Thrill; Heart of Salome with Alma Rubens and Walter Pidgeon; and Harry Langdon in His First Flame (“This is Harry Langdon’s first feature length comedy and for reasons best known to Harry’s former money-making employers, it has just been released. It was made about two years ago and the improvements in pictures in two years are remarkable. Langdon is, was and always will be funny but it is just a plain low trick to show this to audiences. The lighting is bad, the girl’s clothes are a scream–in fact the picture looks like a number of two-reelers pasted together–but Harry is always worth the price of admission”. The “italics” are ours; we have quoted this review at length because it points up something we have often harped on: during this period filmmaking techniques advanced so rapidly that a two-year-old film looked crudely old-fashioned).

POSTSCRIPT to the notes on Sunrise (March 20, 1967)

(1) Since writing the notes for last month’s program, we have learned that Hermann Sudermann’s A Trip to Tilsit, on which the film is based, was a short story rather than a novel. Unlike the film it had an unhappy ending–but it was the man who drowned; the woman was saved, as in the film. But the man was given a more boorish and less likeable character than in the film; losing his life through saving his wife’s thus becomes his act of redemption. The Meyer-Murnau version had quite a different mood, and the happy ending was the correct one for the film (certain masochistic critics to the contrary).

(2) We neglected to mention that Barry Norton, who had a bit part in Sunrise (he was the young man of the couple seen dancing in the ballroom–and later caught smooching when George O’Brien is chasing after the pig), played the leading role in Murnau’s very next film, The Four Devils. Such is Hollywood. A small but spectacular role in What Price Glory brought him into prominence, and he became a popular leading man for the rest of the brief period that remained of the silent era. But he was an ARgeninte, and his accent ruled him out for talking pictures. (This was before Maurice Chevalier came along and proved that an accent could be an asset).

* * *

That’s all for this year. See you in the fall!

Notes by Fraser Macdonald

Leave a Reply