The Lost Squadron (1932)

Toronto Film Society presented The Lost Squadron (1932) on Monday, January 3, 1977 in a double bill with Trouble in Paradise as part of the Season 29 Monday Evening Film Buff Series, Programme 5.

Production Company: RKO Radio Pictures. Executive Producer: David O. Selznick. Director: George Archainbaud. Screenplay: Wallace Smith, adapting a story by Dick Grace. Additional Dialogue: Herman J. Mankiewicz and Robert Presnell. Photography: Leo Tover & Edward Cronjager.

Cast: Richard Dix (Captain Gibson), Mary Astor (Follette Marsh), Erich von Stroheim (Erich von Furst), Joel McCrea (Red), Dorothy Jordan (The Pest), Robert Armstrong (Woody), Hugh Herbert (Fritz), Ralph Ince (Detective), Dick Grace, Art Goobel, Leon Nomis and Frank Clark (Flyers), Arnold Grey.

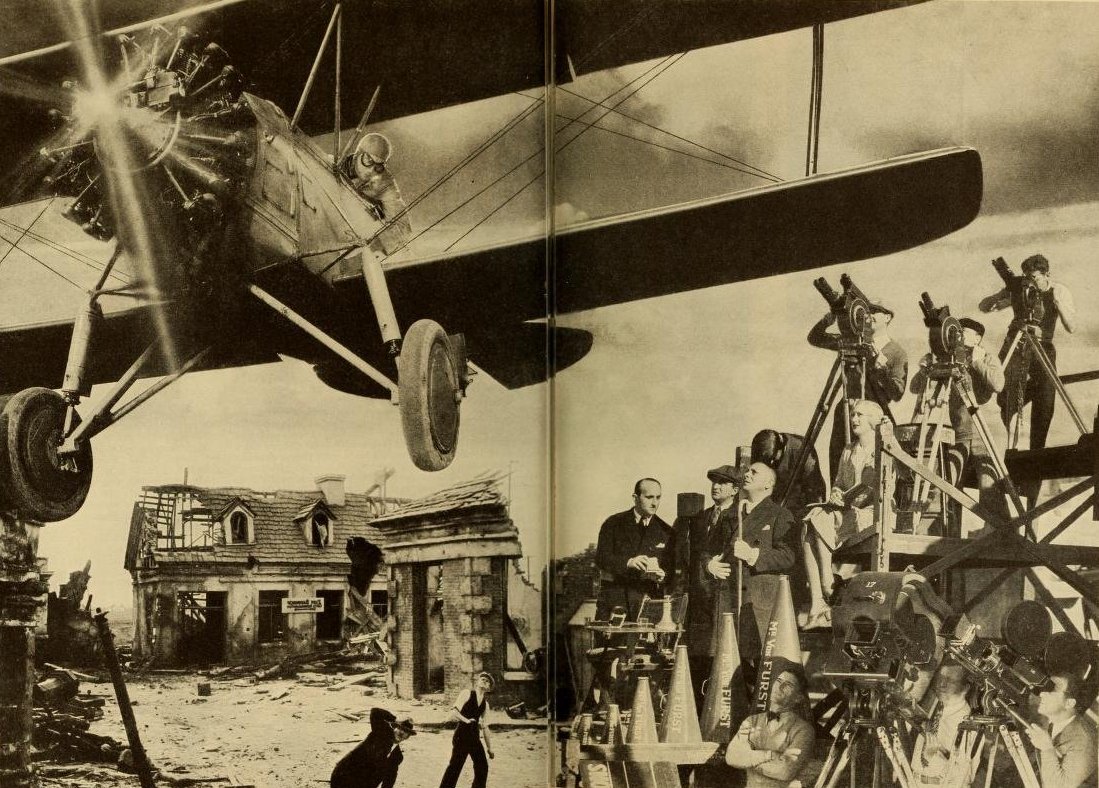

The Lost Squadron is a story about aviators which can boast of a rich vein of originality and clever dialogue. It is an excellent melodrama, ably directed, with a background familiar to producers–for it is chiefly concerned with stunt flying before the cameras in Hollywood and a film director is the evil genius. It races along so effectively that it seems short, whereas it is really a production of the average length.

The narrative is based on one written by Dick Grace, himself a daredevil flyer, who guides one of the machines in the film. As for George Archainbaud, the director, he excels by long odds here anything he has contributed to the screen.

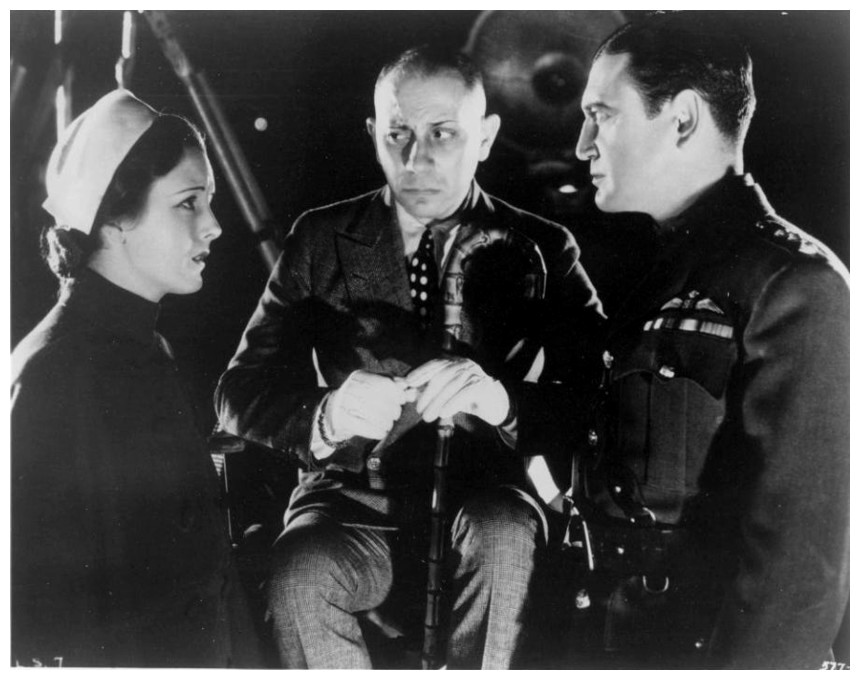

Erich von Stroheim, who years ago was billed by Carl Laemmle as “The Man You Love to Hate”, impersonates Von Furst, a picture director who delights in realism and is always followed by a group of “Yes” men. Mr. von Stroheim once again reveals himself to be a vigorous and compelling actor. He begets attention every instant he is on the screen and toward the close he does two remarkable falls down a flight of stairs. As a director Mr. von Stroheim has always been noted for his desire for realism, and a death glimpsed here is as real as anything he has himself guided in a picture.

The scenes of flying are expertly photographed, particularly the smash-ups and exploding fuel tanks. There are some adroitly conceived dissolves, all of which add to the success of this sterling production.

The New York Times by Mordaunt Hall, March 11, 1932

…A viewing of the film destroyed certain pre-conceived notions and affirmed others. The actual sequences of the shooting of the “film within the film” were conventional in presentation, though the stunt flying itself was extremely exciting. Von Stroheim’s image as “the man you love to hate” was fully explored in a rather hammy performance–his hysterical screaming of: “Keep the cameras rolling! We might catch a nice crack-up,” as a plane plummeted earthwards, when the stunt pilot temporarily lost control; backed by a very mannered, deliberate set of movements like his military gestures raising and lowering his cane in excitement as if he was presenting arms. Others worked, such as the scene in which he berates a group of extras playing soldiers for lacking the correct military posture–an “in” joke as he had been known to drill his extras the previous decade when he was directing a military picture–and the casual arrogance of the sweeping movement with which he flung aside a microphone when he had finished speaking. The presentation of a Hollywood premiere at which the four fliers are re-united, with the flashing sky-writing, the milling crowds, the eager radio interviewer talking to a vapid starlet, who prattles the conventional inanities into his mike; this catches the right atmosphere….

…The direction is uneven throughout, establishing a mood but then allowing it to lag through over-statement or slow development; with the exception of an outstanding sequence in the last reels, shot in an extremely low key, with all sound bar a whining wind cut out. The drama being played out against the setting is extremely tense, establishing a perfect contrast. The performances are competent, with Dix and Astor making the lease impression and Dorothy Jordan the most.

Films and Filming by Kingsley Canham, September 1969

George Archainbaud, adoptive son of actor-director Emile Chautard, was born in Paris May 7, 1890. He started his professional career as actor in his native city until 1915 when he emigrated to the U.S. as assistant director to Chautard at the Fort Lee Studio, N.J. His first film as director was The Iron Ring (1917); his last was The Last of the Pony Riders (1953). Some familiar titles in his filmography: Men of Chance (1932), Thirteen Women (1932), Penguin Pool Murder (1932), Murder on the Blackboard (1932), After Midnight (1933), Her Jungle Love (1938), Thanks for the Memory (1938), The Kansan (1943), The Woman of the Town (1943). He died of a heart attack February 20, 1959 in Beverly Hills. During the last years of his life he had devoted himself entirely to television, his last series being “Lassie”.

Notes written and compiled by Peter Poles

Leave a Reply