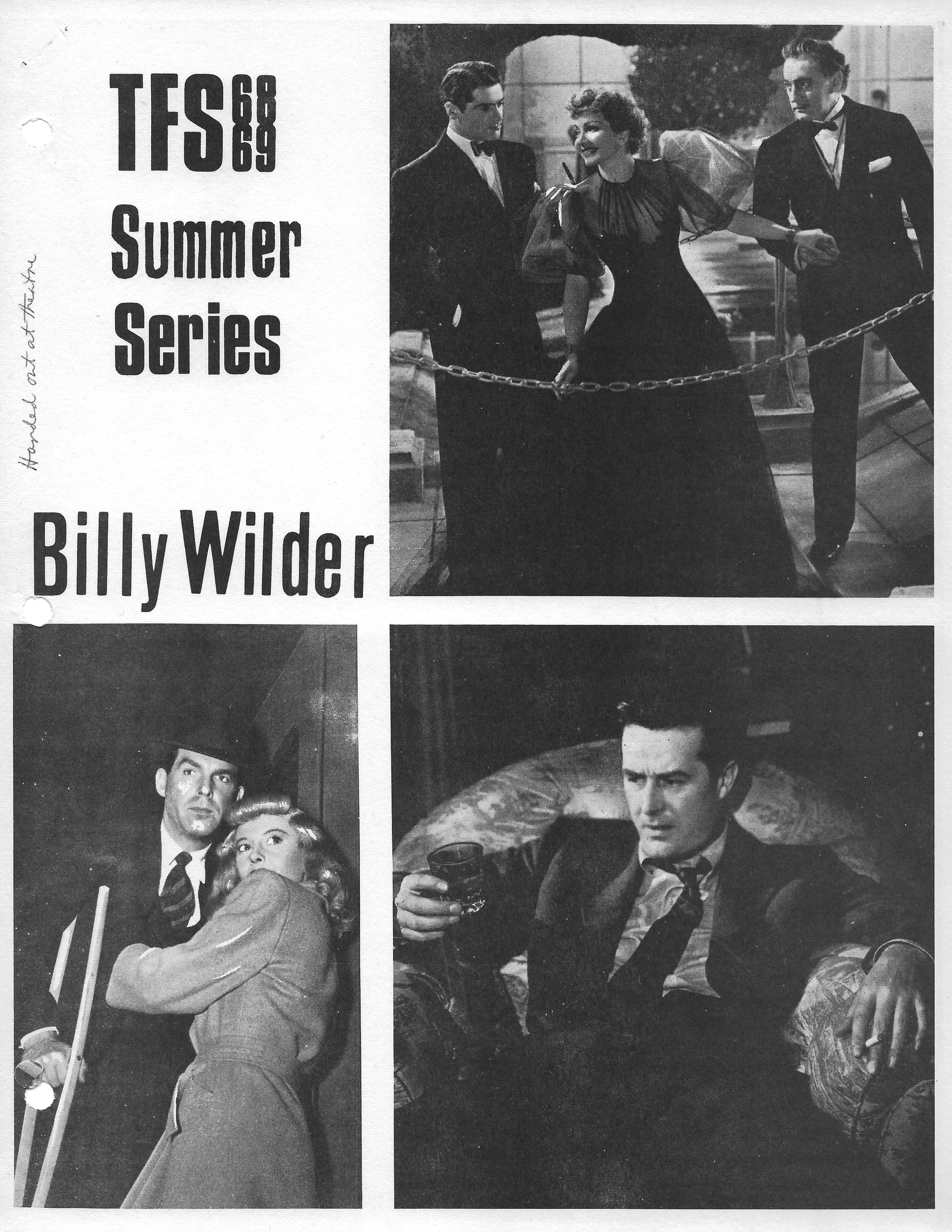

Five Wilder Tuesdays

T O R O N T O F I L M S O C I E T Y — S U M M E R S E R I E S 1969

FIVE TUESDAY EVENINGS AT 8:00 P.M.

AT THE CENTRAL LIBRARY THEATRE, 20 ST. GEORGE STREET AT COLLEGE

Each summer, at the Central Library Theatre, TFS presents a related series of enjoyable movies from the recent or not-so-recent past. We’ve had a Shakespeare, an Orson Welles and a Howard Hawks series, and a marathon season devoted to screen comedy over the years.

This summer we’re offering five programmes based on BILLY WILDER’S PARAMOUNT PERIOD, which many consider his best: four features that he directed for that studio, and a double-bill of films that he scripted–one at Paramount, one in Germany. Wilder’s witty, caustic and individual style has marked him as one of Hollywood’s outstanding writer-directors. Regrettably we weren’t able to track down Sunset Boulevard or Ace in the Hole (The Big Carnival) for this series, but we think the titles listed below will give an excellent idea of Wilder’s way with varied kinds of film–a moving drama and a tough thriller as well as several hilarious comedies.

Concurrently with the Wilder features we are running a mini-Chaplin-Festival–some of Charlie’s funniest shorts will round out the programmes, most of which will also include a Warner Bros. cartoon.

Herewith, then, our schedule:

Tuesday July 15 – Midnight (USA 1939), with Claudetted Colbert, John Barrymore, Don Ameche, Mary Astor.

Plus: Emil and the Detectives (Germany 1932; English subtitles).

Tuesday, July 22 – The Major and the Minor (USA 1942) with Ginger Rogers, Ray Milland.

Plus: Charlie Chaplin in The Adventurer and the Road Runner in Zoom and Bored.

Tuesday, July 29 – Double Indemnity (USA 1944) with Barbara Stanwyck, Fred MacMurray, Edward G. Robinson.

Plus: Charlie Chaplin in One A.M. and Bugs Bunny in Sahara Hare.

Tuesday, August 5 – The Lost Weekend (USA 1945) with Ray Milland (Academy Award), Jane Wyman, Howard Da Silva.

Plus: Charlie Chaplin in Easy Street and Sylvester and Tweety-Pie in Tugboat Grannie.

Tuesday, August 12 – A Foreign Affair (USA 1948) with Jean Arthur, Marlene Dietrich, John Lund.

Plus: A Charlie Chaplin comedy.

********************

The Case of the Missing Patrons

So many movies have opened since the end of our season that I’ve been allowed an extra CFN page. As several of the very best of them closed with equal rapidity, I can’t recommend attendance at the moment; whatever happened tot hat Discriminating Audience we used to be told existed in TO?

But to the films. Most importantly of course there was Shame, Bergman’s powerful, disturbing allegory about humans in wartime, with the magnificent Liv Ullmann out-acting even Max von Sydow and Gunnar Bjornstrand. Here Bergman abandons the complexity and semi-obscurity of his recent works for a strong, simple and straightforward style; like everything he does nowadays, it works impressively.

Another allegory, not so much powerful as subtly and sardonically suggestive, is Jan Nemec’s Report on the Party and the Guests, to o with humans facing the onset of a seemingly benevolent dictatorship. Perhaps more famous for its troubles at home than its reputation abroad, still it’s a genuine achievement, coolly unsettling and sharply observed–a more disciplined job than Nemec’s remarkable debut with Diamonds of the Night.

An unusually interesting if ill-attended double-bill at Cinecity featured one of the most mature and accomplished of the new French-Canadian films, Jean-Pierre Lefebvre’s Il Ne Faut Pas Mourir Pour Ca–an amusing and touching study of an eccentric young man, his mother and lady-friends; beautifully played in its two leading roles. The other feature: Le Socrate, an uneven and idiosyncratic, but often stimulatingly original piece by France’s Robert Lapoujade.

John Krish, once a maker of solid documentaries on such subjects as British schools has come up with a generally hilarious and irreverent comedy on just that topic–Decline and Fall of a Birdwatcher, derived from Evelyn Waugh, full of engaging English eccentrics, and boasting the presence of one of France’s great gifts to the world–Genevieve Page.

Briefly buried in a West-end neighborhood house, Voyage of Silence is a splendid French production (director, Christian de Chalonge) about illegal Portuguese immigrants looking for work in France–close to documentary without a moment’s dullness, involvingly sympathetic without a trace of sentimentality–no mean feat. It has the sort of sharp, clean, beautiful black-and-white photography that is almost a thing of the past, and a performance of complete belief by Marco Pico.

The Birthday Party; early Pinter, not the bet but characteristic (funny, sad, strange, scary, fascinating); director Friedkin did a more inventive job on Minsky’s, but the acting is choice–Robert Shaw, Sidney Tafler, Patrick Magee and Moultrie Kelsall are all admirable, and Dandy Nichols is just wonderful.

Support Your Local Sheriff; one of the year’s sleepers, a very funny comic-Western with a witty script by William Bowers. James Garner and oan Hackett prove adept in this filed and veteran Walter Brennan seems to enjoy doing a sendup of the mean-heads-of-nasty-families he used to play in Ford films.

Jacques Doniol-Valcroze’s Le Viol: an elegant, coolly erotic, quietly intriguing puzzle-picture; Bibi Andersson and Bruno Cremer are as nice a pair of protagonists as you could find to share a lady’s afternoon sex-fantasy.

Bondarchuk’s War and Peace: neither a great movie nor satisfactory Tolstoy, and dubbed and cut to boot; but its visual qualities are often impressive (not only massive spectacle but considerable beauty and imagination), and now and then it is moving as well.

Two films with a World War II background, two male leads, somewhat offbeat themes, flawed by interesting and ably played–The Sergeant (Rod Steiger, John Philip Law) and Hell in the Pacific (Lee Marvin, Toshiro Mifune).

All the above movies have, as I write, vanished without trace; one that’s still around: The Killing of Sister George, Robert Aldrich’s competently “opened-cut” screening of Frank Marcus’ pungently entertaining play about “butch” ladies around the BBC. Beryle Reid, Susannah York and especially Coral Browne are excellent. (Yes, Mr. Silverthorne has shortened the “notorious” seduction scene.)

Written June 5, 1969, for Toronto Film Society

by George G. Patterson

********************

Introduction to the Series

BILLY WILDER: HOLLYWOOD’S BAD BOY FROM VIENNA

He was born in the Austrian capital in 1906. His father wanted him to be a lawyer, but he abandoned his studies in favour of jobs in Berlin as a sports and crime reporter and even a gigolo! It’s said he sold his first film-script to a producer who took refuge in his room on fleeing from the too-early-returning husband of Wilder’s landlord’s daughter. Be that as it may, he wrote many scripts during the next four years, the best known being the silent People on Sunday shown by TFS several years ago, and Emil and the Detectives, included in our first programme this summer. In 1933, along with many other Jewish artists, he left Germany, but had a tough time in Paris, peddling scripts and getting to co-direct a Danielle Darrieux movie called Mauvaise Graine.

He then sold a script to Columbia; it was never produced, but the money brought him to Hollywood where, despite occasional co-writing jobs, two years of penury followed–at one point, it seems, he “moved in with Peter Lorre for fifty cents a day” and the pair lived on cans of soup. Eventually Wilder landed a writing job at Paramount, where he made little impression until someone had the inspired idea of teaming him with Charles Brackett. The two went together, as they say, like ham and eggs, and worked on such successful films as Lubitsch’s Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife and his superb Ninotchka, as well as Howard Hawks’ Ball of Fire and three Mitchell Leisen films–Midnight, Arise My Love and Hold Back the Dawn. Finally in 1942 Wilder was given the opportunity to direct one of their scripts, The Major and the Minor. Later Brackett became producer of their films, and (with the exception of the Brackett-less Double Indemnity) the team worked together until 1950 when, after the brilliant Sunset Boulevard, they parted company. Wilder carried on alone for a time at Paramount, then later for other companies, producing his own films and co-writing them with I.A.L. Diamond.

I’ve always felt there was something missing in the Wilder pictures since the split with Brackett–perhaps it was Brackett’s wit and aplomb as against Diamond’s brashness and (often funny) vulgarity. Some Like It Hot was a tour-de-force of outrageous farce, but for me only The Apartment, of the later films, is of the quality of the better Wilder-Brackett collaborations.

Most commentators agree that no immigrant movie-maker ever more quickly and whole-heartedly absorbed the culture of his adopted land than Billy Wilder. Whatever vestiges of continentalism remain in his style (e.g., a certain German-silent visual touch in Double Indemnity, The Lost Weekend and Sunset Boulevard), his Hollywood films as a director have from the first been thoroughly and unmistakably American. Where critics violently disagree is in their opinion of Wilder’s approach. His champions uphold him as a ruthlessly honest, caustically candid delineator of American life and character, exposing human weakness and corruption in the manner of a latter-day Voltaire. His detractors accuse him of cheap cynicism, cold and heartless misanthropy, “biting the hand that feeds him”, exploiting the very vulgarity and sensationalism he attacks. No one can deny that, for better or worse, his films reflect a strikingly personal, individual view of life rare in today’s Hollywood.

Not all Billy’s pictures have been stark, sordid dramas or melodramas, nor brashly “nasty” comedies. Two that had considerable charm were Love in the Afternoon and Sabrina (but then how caustic can you get with Audrey Hepburn?). Uncharacteristic, too, was The Spirit of St. Louis, a careful reconstruction of the Lindbergh story that didn’t entirely come off.

A charge levelled against Wilder increasingly in recent years is that he compromises for box-office reasons and sugars some of his most bitter pills by injecting false sentimentality or tacking on happy endings. I don’t believe this is true of The Apartment where, for all the folly of their behaviour and the sardonic humour of their situations, there is a basic likability to the Lemmon and MacLaine characters and a genuine empathy developed for them that made me, for one, care what happened to them, rather than feel I was being cynically manipulated. I think the charge is justified, however, in the case of The Fortune Cookie, where the biting portrait of human greed and chicanery in the form of an insurance fraud is sadly diluted by the incredibly sweet and sentimental treatment of the Negro ball-player and the “goodness and happiness” aura of the ending.

In spite of the earthy bluntness of many of his movies, Wilder has rarely run afoul of censorship–but he did stub his toe a bit with Kiss Me, Stupid, which the Hollywood Code people made him soften up a little before release; the Catholic Film Office still gave it a “Condemned” rating, and a number of critics took moral exception to it. Growled Wilder: “What they call dirty in our pictures, they call lusty in foreign pictures!”.

No note on Wilder would be complete without quoting at least a couple of his characteristic acid remarks. One I rather like is: “The New Wave, you watch, will discover the slow dissolve in about ten years or so”. My favourite: While courting his second wife (whose forearms, it seems, we are to see handing Ray Milland his hat as he’s thrown out of a bar in The Lost Weekend), he is reported to have said: “I’d worship the ground you walk on if you lived in a better neighborhood!”.

But to our series! Since we showed Some Like It Hot two summers ago, and The Apartment has been widely shown and re-shown, we decided on a selection from Billy Wilder’s Paramount period, arguably his best. That Sunset Boulevard and The Big Carnival (Ace in the Hole) were not available is regrettable, but we think the titles we’re showing will prove a representative and satisfying lot.

Notes by George G. Patterson

Billy Wilder’s Films as Director

1943 Five Graves to Cairo

1944 Double Indemnity

1945 The Lost Weekend

1947 The Emperor Waltz

1948 A Foreign Affair

1950 Sunset Boulevard

1951 Ace in the Hole (The Big Carnival)

1953 Stalag 17

1954 Sabrina

1955 The Seven Year Itch

1957 Love in the Afternoon

1957 Witness for the Prosecution

1959 Some Like It Hot

1960 The Apartment

1961 One, Two, Three

1963 Irma La Douce

1964 Kiss Me, Stupid

1966 The Fortune Cookie

1969 The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes

References: “Billy Wilder” by Axel Madsen; “The American Cinema” by Andrew Sarris; Film Comments, Summer 1965; Films and Filming, January 1960; Monthly Film Bulletin, December 1967; The Quarterly of Film, Radio and Television, Fall 1952; Sight and Sound, Winter 1956-57, Spring 1963, Winter 1967-68.

Leave a Reply