Destiny (1921)

Toronto Film Society presented Destiny (1921) on Monday, March 28, 1955 as part of the Season 7 Monday Evening Silent Film Series, Programme 5.

TFS presented two short films prior to the feature film:

Meshes of the Afternoon U.S.A. 1943. By Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid.

Concerned with the relationship between the imaginative and the objective reality,–begins in actuality and, eventually, end there. But meanwhile the imagination intervenes. It seizes upon a casual incident and, elaborating it into critical proportions, thrusts back into reality the product of its convolutions. The protagonist does not suffer some subjective delusion, of which the world outside remains independent; on the contrary, she is, in actuality, destroyed by an imaginative action. (Maya Deren)

A girl comes home one afternoon and falls asleep; then sees herself in a dream returning home, is tortured by loneliness and frustrations, impulsively commits suicide. The climax has a double ending in which it appears that the imagined has become the real. Not completely successful–but the cutting, use of camera angles, feeling for apce and movement are realized with sensitivity and cinematic awareness. (Lewis Jacobs)

The World at Your Feet Canada 1954. A National Film Board production.

INTERMISSION – 10 minutes

Destiny Germany 1921. Directed by Fritz Lang. Scenario: Thea von Harbou. Photography: Erich Nitzchmann, Fritz Arno Wagner. Design: Walther Rohrig, Robert Herlth, Hermann Warm.

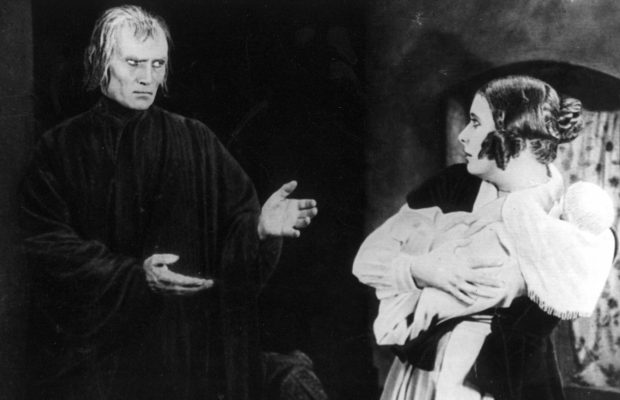

Cast: Bernard Goetzke, Lil Dagover, Walther Janssen , Rudolph Klein-Rogge, Georg John.

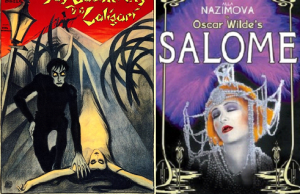

One of a group of German fantasy films of the 20’s–nearly allentirely studio-made, whole palaces and streets being built. Destiny, The Golem and Waxworks were equally superb in their creative architecture. This feeling for decoration, for simple but rich design, in the Dureresque and Baroque styles, was the real basis of the German studio-mind. Even in popular films this wonderful sense for good design was prevalent. Unlike other countries, German experimentalists were able to embody their revolutionary ideas in films of general practicability. There was almost no German avant-garde school at that time, for the most advanced filmic intelligences were working in the commercial studios. This accounted to a large extent for the superior aesthetic value of the German film. Destiny, Siegfried and Metropolis were evidence of the fertility of Lang’s imagination and his sense of decorative design; and were supreme examples of the German art film. In each, the decorative value of the architecture was the binding force of the realization. Finely created, using every contemporary resource of trick photography and illusionary setting, Destiny had an interplaited theme of three stories, each connected symbolically with the acting–a production too soon forgotten–deserves revival. (Paul Rotha)

Revealed the talents of a really able director. The opening sequence is admirable–later the film tends to become a series of big spectacles, though many interesting effects are obtained with real skill–a curious power to stir the imagination. (Bardeche and Brasillach)

After the release of Destiny, which in Germany was called The Tired Death, a sarcastic Berlin critic entitled his review The Tiresome Death. But when the French praised the work for being truly German, the Germans also discovered its value, and what had at first seemed a failure developed into a complete victory on the home front. The long-lived power of Destiny‘s imagery is the more amazing as all had to be done with the immovable, hand-cranked camera and night shots were still impossible. These pictorial visions are so precise that they sometimes evoke the illusion of being intrinsically real. A “drawing brought to life”, the Venetian episode resuscitates genuine Renaissance spirit through such scenes as the carnival procession, silhouettes staggering over a bridge, and the splendid cockfight radiating bright and cruel Southern passion in the mode of Stendhal or Nietzche. The Chinese episode abounds in miraculous feats, inspiring Fairbanks to make The Thief of Bagdad. The plot forces strongly upon the audience that, however arbitrary they may seem, the actions of tyrants are realizations of Fate. The agent of Fate supports tyranny not only in all three episodes but also in the story proper. By humanizing Fate, the film emphasizes the irrevocabilitiy of Fate’s decisions. It is as if the visuals were calculated to impress the adamant, awe-inspiring nature of Fate upon the mind. (Siegfried Kracauer in From Caligari to Hitler)

Leave a Reply