Easy Living (1937)

Toronto Film Society presented Easy Living (1935) on Monday, July 21, 1986 in a double bill with The Big Broadcast of 1938 as part of the Season 39 Summer Series, Programme 3.

Production Company: Paramount. Producer: Arthur Hornblow Jr. Director: Mitchell Leisen. Screenplay: Preston Sturges, based on an upublished story by Vera Caspary. Photography: Ted Tetzlaff. Editor: Doane Harrison. Art Direction: Hans Dreier, Ernst Fegté. Costume Design: Travis Banton. Music: Boris Morros. Release Date: July 7, 1937. Shooting: April 12 to May 24, 1937.

Cast: Jean Arthur (Mary Smith), Edward Arnold (J.B. Ball), Ray Milland (John Ball, Jr.), Luis Alberni (Mr. Louis Louis), Mary Nash (Mrs. Ball), Franklin Pangborn (Van Buren), Barlowe Borland (Mr. Gurney), William Demarest (Wallace Whistling), Andrew Tombes (E.F. Hulgar), Esther Dale (Lillian), Harlan Briggs (Office Manager), William B. Davidson (Mr. Hyde), Nora Cecil (Miss Swerf), Robert Greig (Butler), Vernon Dent (1st Partner), Edwin Stanley (2nd Partner), Richard Barbee (3rd Partner), Marsha Hunt (Bit), Lee Bowman (Bit), Gertrude Astor (Saleswoman), etc.

Although Easy Living is today regarded as one of the classic screwball comedies of the era, it was considered nothing special when made, and barely made back its costs at the box office. VARIETY called it “slapstick farce, incredible and without rhyme or reason”, and Frank Nugent, of The New York Times, concurred: “It doesn’t, as any one can see, make much sense, and a good bit of it is incredibly reminiscent of those old custard pie and Keystone chase days”.

Preston Sturges had become a staff employee of Paramount in September of 1936, and the story of “Easy Living”, by Vera Caspary, was to be his first script. Caspary’s story was a routine romance of a poor girl who steals a mink coat, and thus attired, sees her life changed entirely. One deception is piled atop another, until her life is in ruins and she is left with nothing. Sturges junked the entire story–salvaging only the plot device of the mink coat–and started work on an original comedy under the same title. What resulted was perhaps the perfect example of “screwball” or “madcap” comedy. Lewis Jacobs, in “The Rise of the American Film”, gave a memorably contemporary account of this genre: “The loss of credibility in former values, the breakdown of the smugness and self-confidence of the jazz era, the growing bewilderment and dissatisfaction in a ‘crazy’ world that does not make sense, has been reflected in the revival of comedies of satire and self-ridicule. ‘Daffy’ comedies became the fashion. Here the genteel tradition is ‘knocked for a loop’: heroes and heroines are neither ladylike and gentlemanly. They hit each other, throw each other down, mock each other, play with each other. …These films were all sophisticated, mature, full of violence–hitting, falling, throwing, acrobatics–bright dialogue, slapstick action–all imbued with terrific energy”.

Easy Living was essentially a brilliant lampoon of the Cinderella story, the tale of a penniless stenographer who is installed in a penniless hotel because the hotel manager thinks she is the mistress of J.B. Ball, the Bull of Broadstreet. Cinderella films, with the heroine searching for her Prince Charming, grew and flourished in the Depression thirties. Early versions–The Devil’s Holiday (1930), with Nancy Carroll; Hot Saturday (1932), also with Miss Carroll, who seemed to dominate this genre in early talkies as she dominated the era itself; They Call It Sin (1932), with Loretta Young; Midnight Mary (1933); Bought (1931), Compromised (1931); Shopworn (1932); She Wanted a Millionaire (1932) et al, with Barbara Stanwyck, or Kay Francis, or Ruth Chatterton–were basically heavy melodramas laced with raw emotion. By the mid-thirties this was changing, with first comedy and then satire entering the genre. Films such as The Good Fairy, Hands Across the Table, The Gay Deception, The Bride Comes Home (all 1935) and I Met Him In Paris (1937) increasingly enlivened the genre until the crowning glory of Easy Living and later Midnight. In the standard Cinderella comedy, the heroine’s persistence (a la the gold digger) usually has her fall in the lap of luxury–in Easy Living, it is luxury that falls into the heroine’s lap in the form of a fur coat tossed by an irate millionaire. Sturges’ witty dialogue is augmented by Leisen’s decision to accent old-time slapstick–resulting in a classically timeless, sparkling comedy masterpiece. It starts right at the beginning, when the millionaire (Edward Arnold at his boisterously blowing best) goes tumbling down the stairs and lands with a crash at the bottom. His butler says, “I see you’re down early today, sir.”

The cast of Easy Living is a constant delight, for Paramount always seemed to have the most memorable supporting people in their films. Edward Arnold (1890-1956)’s J.B. Bull is virtually a starring role, and the real centre of the film. Luis Alberni (1887-1962)’s Louis Louis delivers some of his most Goldwynesque malapropisms–“What a place to flop”, describing his own luxury hotel. Franklin Pangborn (1893-1958), William Demarest (1892-1983), Andrew Tombes (1889-1975) and Robert Greig (1880-1958) gave the film individuality and character. Jean Arthur (born 1905) was one of the most enigmatic actresses in film history. Although she started in film in 1923 with a brief part in John Ford’s unremarkable Cameo Kirby, and finished her film career with George Stevens’ unforgettable masterwork, Shane, in 1953, Jean Arthur was a “star” force in film for only about ten years, again between John Ford’s The Whole Town’s Talking (1935) and George Stevens’ The More The Merrier (1943). In the interval, Jean Arthur, usually as a radiantly high-spirited working girl with an enchantingly husky voice, childishly querulous at one moment, deeply reassuring the next, endowed filmgoers with aunique accumulation of accomplishments–who can forget Jean Arthur in Capra’s Mr. Deeds Goes To Town (1936), DeMille’s The Plainsman (1936), Borzage’s incandescent History Is Made at Night (1937), Easy Living, Capra’s You Can’t Take It With You (1938), Hawks’ Only Angels Have Wings (1939), Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), Ruggles’ underrated Too Many Husbands (1940), Wood’s The Devil and Miss Jones (1941) and Stevens’ The Talk of the Town (1942)? Yet Miss Arthur was extremely shy and self-conscious about her film acting–a trait she shared with another uncommonly warm actress with another unfortunately brief star career–Margaret Sullavan. Mitchell Leisen’s secretary, Eleanor Broder, offered: “Everybody in Hollywood was always talking about how difficult Jean Arthur was to work with, but we didn’t have any trouble with her at all. She was on the set on time every morning and she knew all her lines. She was painfully nervous and she stuttered terribly through the rehearsals. But the minute the camera turned, she was fine, she became a completely different person, brash and sure of herself. She was terribly concerned with the way she looked on the screen. Mr. Leisen came in the week before and personally directed all her wardrobe and hair tests, he even styled her hair himself. She was very pleased when she saw the results, and from that moment, she had complete trust in Mr. Leisen. Mr. Leisen always said, ‘If an actress is satisfied with the way she looks on the screen, she’ll devote all of her attention to her acting,’ and he was right”.

Notes by Jaan Salk

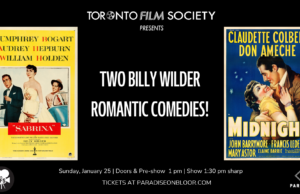

Sunday Afternoons at the Paradise

Join TFS for Season 78’s Sunday Matinée Series generously sponsored by our good friend, author and documentary filmmaker, Mr. Don Hutchison. Please save this date and visit us regularly...