I Was a Fireman (1943)

Toronto Film Society presented I Was a Fireman (1943) on Monday, April 21, 1952 as part of the Season 4 Main Series, Programme 9.

NINTH EXHIBITION MEETING – FOURTH SEASON

Monday, April 21, 1952 8.15 p.m. sharp

Royal Ontario Museum Theatre

A PROGRAMME OF FILMS

BY HUMPHREY JENNINGS

Words for Battle (1941) 8 mins

Listen to Britain (1941) 18 mins

I Was a Fireman (1943) 75 mins

I see London

I see the Dome of Saint Paul’s like the forehead of Darwin

I see London stretching away North and North-East along dockside roads and balloon-haunted allotments

Where the black plumes of the horses precede and the white helmets of the rescue-squad follow . . .

I see the green leaves of Lincolnshire carried through London on the wrecked body of an aircraft –

These lines from a poem by Humphrey Jennings suggest a sequence from one of his films, not simply because of their visual emphasis, but for their juxtaposition of image and image–the kind of simile or ‘inspired incongruities’–which gives his films their extraordinary, intense personality. This constant element of surprise, the procession of emotional and intellectual correspondences which was the basis of Jennings’ style as a film-maker … stems no doubt from his first vocation: he began as a painter, and his pictures were surrealist in manner. His passion for the cinema, those who knew him well have said, arose from his growing interest in the collective spirit, which led him in fact from Mass Observation (the movement founded by Charles Madge) to mass communication.

Of the 16 films Jennings made on his own, ten are concerned directly with aspects of the English scene. This country–its landscapes and its cities, its people, its business and leisure, its past and present–he approached full-face and profile; officially all the portraits were commissioned, since they were films produced for government departments, and many of them carry a strong sense of occasion; yet nearly all of them are intimate, some are capricious and only two that I have been were subdued by having to present a case. This in itself is no mean achievement in documentary, where for the last ten years pressure on this individual has been as strong in its way as it has in the studios.

Gavin Lambert, Sight and Sound May 1951

Humphrey Jennings, at the age of 43, was accidentally killed while making a film in Greece over a year ago. Among the most celebrated films into which, between 1939 and 1950, he poured his love of Britain and of human beings were–Spare Time, Spring Offensive, Listen to Britain, The Silent Village, I Was a Fireman, sometime called Fires Were Started, The Story of Lilli Marlene, Diary for Timothy, A Defeated People, The Cumberland Story, Family Portrait. Few of these had public showings in Canada, though London Can Take It, on which he collaborated, was widely shown in 1940. His last film, Family Portrait was screened at the Society’s Special Showing last Season and at the International Cinema.

Critic Dilys Powell commented on a B.B.C. broadcast: “Jennings was an artist and a poet; he wasn’t simply a shaper of the visual image, he was a man who had a feeling for words, and for music as well. From four elements–the image of the thing seen, from the written or the spoken word, from music, and the sound of life going on–from all these elements he made a picture of England as he knew it. The picture was unequal; sometimes it was quite commonplace; but at its best it was moving and exciting and intense. We haven’t so many artists in the cinema that we can afford to forget Humphrey Jennings.”

In marked contrast to Words for Battle, a short piece with quotations from Camden’s “Britannia”, Milton, Blake, Browning, Kipling, Churchill and Lincoln spoken by Sire Laurence Olivier is Listen to Britain–an experiment in relating wordless sound and picture. “This is a wonderfully sensitive evocation of Britain at the beginning of the second year of the war. … The technique of Listen to Britain is based completely on the power of association. The soundtrack and the camera range through a variety of scenes and incidents … here are the everyday sounds of the British Isles drawn from street, factory and field, from the places of work and entertainment, from shunting trains to Myra Hess playing the piano in the National Gallery. While we listen the camera leaps or wanders, adding its emphasis or comment and helping set the mood that comes mainly from the sound track. …

Not the least striking quality of Listen to Britain is its glimpses of ordinary people … caught with such quick affection and precision, without a trace of patronage or caricature. This is an almost unique achievement in the modern cinema, and Jennings’ ability to make contact with all kinds of people, to present them naturally, acutely observed, shows at its strongest in Fires Were Started (I Was a Fireman), one of his most ambitious films, and his masterpiece.

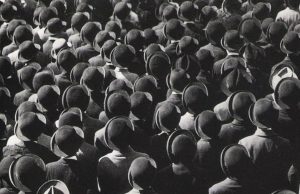

I Was a Fireman is the story of an N.F.S. sub-station in London during the blitz; the tempo and character of the group in its hours of leisure and stand-by, the tension, comradeship and casualties of actual firefighting. Again the approach is impressionistic. Jennings build up his picture of the men at the station, their relationships to each other, emphasising now one character, now another: in the literal sense there is not much construction, and an impatience with narrative as such, but the personality behind the film never falters.

… The whole picture crystallises most strikingly in the sequence when, as the men wait in the recreation room for a call during a night raid, Sansom at the piano plays in each fireman as he enters, to the tune of “One man went to mow”. This is an unforgettable piece of human observation showing Jennings’ talent from every angle: it is at once humorous, ironic, touching, affectionate, a scene of perfect spontaneity in itself and of strong dramatic effect in its context.

The second half is as concentrated as the first is leisurely and digressive; the dockside firefighting scenes, excitingly directed and photographed. Here again, though the emphasis is on the action, the increasing ravages of the fire and the attempts to stop it before it spreads to a warehouse stored with explosives, Jennings does not lose sight of the characters. There has been no other British film about the war like I Was a Fireman, and when seen again today its poetic statement, its wide human sympathies encompassing both particular figures and particular happenings, and yet evoking the whole atmosphere of London under fire, appear as something unique.” (Gavin Lambert)

NOTE: I Was a Fireman is a 35mm print; as there is only one 35mm projector in the booth – 3 pauses, of 3 to 4 mins. each, are necessary for change of arc and re-threading.

There is no intermission tonight.

ANNOUNCEMENTS

- This year’s CANADIAN FILM AWARDS will be presented and the winning films screened in Toronto, Sunday evening April 27th at the Victoria Theatre. The Canadian Association for Adult Education and the Canadian Association of Motion Picture Producers and Laboratories cordially invite members of Toronto Film Society to attend. Invitation cards are available in the Lobby tonight for those who are able to accept.

- Advance application forms requesting membership in the Society’s 1952-53 Season are available in the Lobby; the Secretary will accept membership fees tonight ($10.50 – Double; $6.50 – Single; $3.50 – Students)

The 1952-53 Season opens September 22nd with Jean Cocteau’s Orphée.

CURRENT FILM NOTES

Five Fingers is an astonishing movie. Its director, Joseph Mankiewicz displays almost no film style at all and never makes a point visually when he can make it ve..ally; its alleged “true story” seems somewhat open to doubt to say the least; its hero is a completely unprincipled freelance spy who sells top secrets to the Nazis, not from patriotic or political convictions but purely for gain; yet the show is completely fascinating and absorbing entertainment, told in its way with smoothness and polish, and, willy-nilly, you find yourself pulling for the rogue every foot of the way!

Charles Chichton, who made Hue and Cry and The Lavender Hill Mob turns to melodrama with Hunted, but shows the same assured command of his materials and his medium as with comedy. Though it’s a chase thriller, character is not neglected; Dirk Bogarde’s acting is better than I thought him capable of, and the youngster Jon Whiteley is wholly convincing and winning.

The Boulting Brothers’ High Treason is another efficient British thriller, but not of the same calibre as their Seven Days to Noon. The Man in the White Suit, one of the best of the Alec Guinness pictures, seemed to have had a disappointingly brief first run. If you missed it, by all means catch it at one of the Odeon’s second-run houses where it is the Easter attraction.

Just in case you haven’t seen Manon, you’ll find it a lively, virile and engrossing modern version of the old yarn; director Clouzot’s work is worth watching, though the yound leads sometimes lack the acting maturity to project the required emotions.

George G. Patterson

MEMBERS’ EVALUATIONS

The End of St. Petersburg: “Enjoyed this film so much it is difficult to single out particular scenes for praise; propaganda or not, a good portrayal of life at that time in Russia; extremely well cast”—“Contains brilliant sequences which are still exciting–moving and surprising ending; as a film=maker Pudovkin seems to me superior to Eisenstein; in silent era Russians brilliant, uneven experimenters, but Germans much more consistent and sold”—“Several smartly-made sequences; ending a minor masterpiece, subtle and entirely successful; but some experimental sections completely un-valid today, and one section as corny and poorly made as can be seen; but on the whole a worthwhile effort, though no masterpiece not worthy to be compared with, say, Greed“—“Told dynamically, poetically; a bit redundant in its parallel cutting but overall terrific”—“Wonderful portrayal of times”—“a great classic with political impact told in a human moving way”—“Social contrast of the times well displayed”—“Best film of the year; we should have many more”—“The section of the elevator was good and the end–the rest was fair enough in its time as an experiment; interesting, but seeing it does debunk some of the misinformation which comes from Pudovkin’s book.”

Some thought the film too long; several members commended the music score, but some felt it failed to rise to the film’s climax, and one found the repetitive theme in the first movement of Shostakowich Symphony #7 tedious.

Newfoundland Scenes: “Excellent”—“Wonderful, a real advance in Canadian documentary; clear sharp photography, correct colors”—“Impressive, epic, engrossing; a Canadian classic; beautiful print visually and aurally”—“Particularly enjoyed this and hope I will have the opportunity of seeing it again”—“Best color I’ve ever seen”—“Best documentary I’ve ever seen; but would have been improved by being told in more personal terms”—“Thrilling each time I see it and I’d like to see it again; this may possibly be the great Canadian documentary”; this last member goes on to discuss at some length his feeling that the film’s qualities are due more to its striking, exciting content and the exceptional clarity of the visuals and sound than to the treatment; “the director does not use all the resources of the cinema to the full”.

And just for a change, someone has a good word for the audience! “Thanks again for the privilege of seeing wonderful films under such good conditions; this last is a compliment to our audience which I find is very good, patient and understanding.”

Leave a Reply