Island of Lost Souls (1932)

Toronto Film Society presented Island of Lost Souls (1932) on Sunday, October 28, 2018 in a double bill with Freaks as part of the Season 71 Sunday Afternoon Special Screening #4.

Production Company: Paramount Pictures. Director: Erle C. Kenton. Screenplay: Waldemar Young, Philip Wylie, based on the novel by H.G. Wells, “The Island of Dr. Moreau”. Cinematography: Karl Struss. Music: Arthur Johnston, Sigmund Krumgold. Art Direction: Hans Dreier. Release Date: December, 1932.

Cast: Charles Laughton (Dr. Moreau), Richard Arlen (Edward Parker), Leila Hyams (Ruth Thomas), Bela Lugosi (Sayer of the Law), Kathleen Burke (The Panther Woman), Arthur Hohl (Montgomery), Stanley Fields (Captain Davies), Paul Hurst (Donahue), Hans Steinke (Ouran), Tetsu Komai (M’ling), George Irving (The Consul).

Genetics is the star of today’s double bill. Both feature Leila Hyams, who, one could argue was genetically predisposed towards acting, as both her parents, John Hyams and Leila McIntyre, were actors who tried their luck in Hollywood when Vaudeville ran its course. Although they worked in about three dozen films between 1927 and 1941, they never succeeded past playing minor roles while their daughter became a big name, making more than 50 feature films between 1924 and 1935, then choosing to be a stay-at-home wife until her death at the age of 72 in December 1977. But the most important genetic aspect these two films share is scientific altering versus natural birth.

The 1896 novel, The Island of Dr. Moreau, by H.G. Wells was purposely written due to Europe’s growing discussion regarding opposition towards degeneration and animal vivisection. The novel reflected these themes, along with the ideas of Darwinian evolution which were gaining popularity and controversy in the late 1800s.

The Island of Lost Souls’ frank references to vivisection and Moreau’s delight in “feeling like God” assured the banning of the film in twelve countries, including England, where it was described as being “against nature.” In America, state censors—established in the wake of a 1915 Supreme Court ruling that motion pictures were not protected speech—cut various lines and scenes, depending on local standards and tastes. Nonetheless, people were reportedly so repulsed that they vomited in their seats.

However, today’s audiences won’t be affected by this 1932 film in the same way with 86 years separating what was considered horror then to what is the laisse fair attitude towards horror now. Also, if you grew up in the 80s, you will automatically conjure up the band Devo when you hear Bela Lugosi as the Sayer of the Law intone “Are we not men?” and that would make sense since this was the film that highly influenced the band’s beginnings.

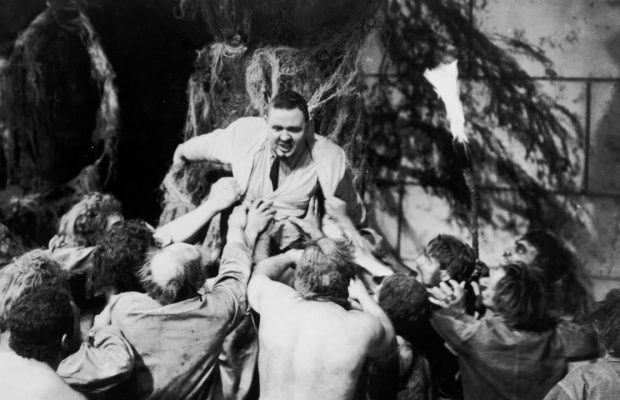

But what continues to rattle us, whether we’re watching something in the modern era such as The Sopranos where the act of one person taking another’s life is a constant threat, is being horrified while the torturer is finding pleasure in letting the victim know that no matter what is said or done to try to assay the situation, these are his or her last moments of life. These same feelings are still there now when we begin to understand the depth of depravity that Moreau leashes on his victims in this 1932 film.

Charles Laughton, as Moreau, is creepy and controlled, with an unsettling undercurrent of ambivalent sexual energy. And although bestial desire on the part of our hero played by Richard Arlen somewhat sickens him, the real threat here is miscegenation. Early 1930s horror was preoccupied with creatures that resemble normal men but are in some way deformed, deranged, or awfully and miserably inhuman, confirmed in 1932 films such as Frankenstein, Dracula, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and Freaks. With Island of Lost Souls coming out in the Jim Crow era, it trades in dark makeup and broad noses, while combining the indigenous and non-white human with the animal. The source of the infamous line, the natives “are more than usually restless tonight” originates from Island of Lost Souls as well. In Australia, the film received a rating of NEN, meaning it wasn’t to be shown to aboriginal people, who, presumably, might have taken the flouting of the law designed to make them human, too much to heart. How unbelievable is that?

Charles Laughton was a great actor and of all the versions of this film, there is no one quite like him as Dr. Moreau. However, he was disgusted by the story, particularly due to his love of animals and felt a deep-seated repulsion of the crude exploitation of the theme of vivisection. He was also quite dismayed by the director, Erle C. Kenton, who insisted on acting out scenes dressed up in Moreau’s white tropical suit and hat, even offering to teach Laughton how to handle a whip, forgetting that Charles already had knowledge of this skill by having learnt it from a London street performer for an earlier stage role. Yet, despite Laughton’s strong dislike of the part, he was surprisingly committed. His character’s repulsiveness is relieved by a cunning humour, the confidence by a creeping sense of fear that he may have taken on more than he can handle. Moreau in Laughton’s hands goes much deeper than H.G. Wells could suggest: a perversion of a British Colonial administrator, and at the same time a symbol of Colonial repressiveness. More than any other actor who played this role, Laughton can involve us in a character by no longer being a remote and improbable figure, but by becoming Dr. Moreau.

The film was shot by cinematographer Karl Struss on Catalina Island, where so many Hollywood films that needed to take place in an exotic locale were filmed (Rain, Treasure Island, Captain Blood, Mutiny on the Bounty and Captains Courageous to name a few). Art director Hans Dreier is credited with working on 541 films. He contributed to the early films of directors such as Lubitsch and Von Sternberg, beginning his career in Germany in 1919, moving to Hollywood in 1924, nominated for an Oscar on 23 occasions and winning for three.

So with all this in mind, I hope you enjoy—if enjoy is the right word—Island of Lost Souls.

Sourced: Charles Laughton: An Intimate Biography by Charles Higham (1976); Vaudeville Old & New: An Encyclopedia of Variety Performers in America: Volume 1 by Frank Cullen with Florence Hackman and Donald McNeilly (2006); Criterion Notes, The Beast Flesh Creeping Back by Christine Smallwood (2011); Wikipedia; IMDb

Introduction by Caren Feldman

H.G. Wells did not mince words when discussing the film adaptation of his 1896 novel: “If you want to know, I think ‘The Island of Dr. Moreau’ as a film was terrible—terrible! You can print that, if you want to…. No subtlety was used in the creation of the dreadful atmosphere. The whole thing was so ridiculously obvious that I must repeat—it was miserable.” This assessment makes horror historian Leonard Wolf’s opinion that frequent Tod Browning collaborator Waldemar Young and Philip Wylie’s screenplay improves upon the source even more audacious. Wolf contends that the erotic elements of the film, “the heady stuff”, as he puts it, surrounding The Panther Woman transcends the more scientific-minded approach of the novel.

Paramount saw an opportunity, in the way only Hollywood in the pre-Code era could, to elevate the bipedal feline character (Puma in the novel) and exploit the bestial sexuality vein at which Wells had merely hinted. The studio held a nationwide audition for the role. From Portland to Poughkeepsie, some 60,000 hopeful women, ages 17-30 and with two cosigners “endorsing her morality”, each sent in an entry form accompanied by a photograph to win a five-week contract at $200. a week with the option of an extension. The fine print indicated that The Panther Woman’s wardrobe would be provided—hilariously ungenerous, considering it was nothing more than a sarong and a beaded necklace. A panel consisting of Cecil B. DeMille, Ernst Lubitsch, Norman Taurog, Erle C. Kenton, and Stuart Walker chose 19-year-old Kathleen Burke, a copy writer from Chicago, to live the Hollywood dream. This newcomer, in Leonard Wolf’s words, “…walks away with the acting honors in this film”. Burke would parlay this opportunity into a modest film career for the next few years before retiring from the screen at the age of 25.

Such is the alchemy of makeup, Karl Struss photography, and a soundstage-turned-muggy-tropical-island that a young nobody could upstage Charles Laughton. Having already made his mark on the British stage (and, incidentally, three comedic short films written by friend H.G. Wells made with his soon-to-be wife Elsa Lanchester), Laughton graced the American screen with decadent villainy in Devil and the Deep and Sign of the Cross (playing Nero) before portraying whip-cracking vivisectionist Dr. Moreau. Wolf gives him his due: “…He looks absolutely transfigured: but it is the transfiguration of an egotist into a God.”

Besides sharing at least one cast member, Leila Hyams (Schlitzie, the pinhead, has long been rumoured to be amongst the beasts), both this film and Freaks concern a group of unified “monsters” frenzying to a revolt. With its thick, oppressive atmosphere Island of Lost Souls is closer to dark fantasy, while Tod Browning’s film has a stark plainness. One relies on pounds of makeup, the other simply shines a light on a real person. Still, both films were banned in the U.K. for roughly 30 years, showing just how dangerous the censorship boards saw these films.

Sources: Katzman, Pearl, “H.G. Wells Talks About the Movies!” Screenland Magazine, July 1935; Skal, David J., The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1993; Smith, David C., H.G. Wells: Desperately Mortal. London: Yale University Press, 1986; Various newspaper articles, including “Unknown Girl to Play Lead in ‘Panther Woman’” (1932, July 31). Los Angeles Times; Wolf, Leonard. Horror: A Connoisseur’s Guide to Literature and Film, New York: Facts on File, 1989

Notes by Adam Williams

Leave a Reply