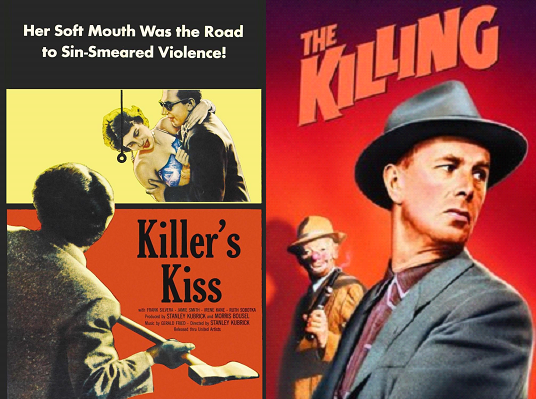

Killer’s Kiss (1955) and The Killing (1956)

Toronto Film Society presented Killer’s Kiss (1955) on Monday, January 30, 1984 in a double bill with The Killing (1956) as part of the Season 36 Monday Evening Film Buffs Series “B”, Programme 6.

Killer’s Kiss (1955)

Production Company: United Artists. Producers: Stanley Kubrick and Morris Bousel. Director, Photography, Editing: Stanley Kubrick. Script: Stanley Kubrick and Howard O. Sackler. Music: Gerald Fried. Choreograhy: David Vaughan.

Cast: Frank Silvera (Vincent Rapallo), Jamie Smith (Davy Gordon), Irene Kane (Gloria Price), Jerry Jarret (Albert), Ruth Sobotka, Mike Dana, Felice Orlandi, Ralph Roberts, Phil Stevenson, Julius Adelman, David Vaughan, Abe Rubin.

The Killing (1956)

Production Company: United Artists. Producer: James B. Harris. Director: Stanley Kubrick. Script: Stanley Kubrick, based on the novel “Clean Break” by Lionel White, additional dialogue by Jim Thompson. Photography: Lucien Ballard. Editor: Betty Steinberg. Art Director: Ruth Sobotka Kubrick. Music: Gerald Fried. Sound: Earl Snyder.

Cast: Sterling Hayden (Johnny Clay), Jay C. Flippen (Marvin Unger), Marie Windsor (Sherry Peatty), Elisha Cook, Jr. (George Peatty), Coleen Gray (Fay), Vince Edwards (Val Cannon), Ted de Corsia (Randy Kennan), Joe Sawyer (Mike O’Reilly), Tim Crey (Nikki), Kola Kwariani (Maurice).

Stanley Kubrick’s films, on the one hand, are visual art (as films should be), and on the other, deal with ideas; but that does not detract from the fact that Kubrick puts together films which are entertaining, aesthetically pleasing, and thought-provoking–all at the same time.

Kubrick is, among other things, a true screen poet. He knows how to use visual images to communicate. He believes that film should probably never communicate anything with words that could be communicated with an image. He can characterize a gangster by the way he handles a gun in The Killing, a strange family triangle by a peck on the cheek in Lolita, a mad general by the way he chomps his cigar in Dr. Strangelove. Kubrick is able to blend theme and imagery most naturally in his films.

Killer’s Kiss is certainly the most atypical of Kubrick’s films. It is a film that took many years to be re-released, because Kubrick considers it to be very weak. It is a “naturalistic” thriller, shot from his own screenplay. It wavers and lacks the obsessional drive of the later films, as do the characters. Killer’s Kiss is most successful in creating the ambiance of lower-class New York life. Although Killer’s Kiss deals in the shabby details of lower-class life, the characters pay little attention to their economic and social plights. They focus on dream worlds which provide specious relief.

Killer’s Kiss inevitably involved Kubrick in far more editing and more technical know-how than did his earlier films, Fear and Desire (1953), Flying Padre (1951), Day of the Flight (1951). Except for a few scenes with the boxer and the girl in their tenement rooms, which were shot in a tiny studio, it was all done on New York locations.

In Killer’s Kiss, Kubrick explores the internal states of nightmare and doubt, through a commercially viable narrative form. The story and style of the film evoke both the darkly romantic atmosphere of “film noir,” and the melodramatic realism of such popular street films as The Naked City (1950), and Panic in the Streets (1950). The film also shows Kubrick’s continuing interest in the psychological subject matter of basic emotional states (fear, desire, loneliness, and entrapment).

If Killer’s Kiss were Kubrick’s highest achievement, it would not merit much more than a quick look; but, because it is the early work of a filmmaker of Kubrick’s credentials, it is worth considering. Kubrick very quickly overcame most of the shortcomings in this film when he released The Killing a year later.

During the 1983 Festival of Festivals a film called Stranger’s Kiss was screened, which enacts in fiction the making of Stanley Kubrick’s Killer’s Kiss. Using actors who bear a stunning resemblance to the true leads of Killer’s Kiss and to Kubrick himself, the film is a homage to the inventiveness of the earlier film, such as in the mannequin storeroom, the romantic dancehall scenes, and the unbelievable scene in the train station.

The Killing is Kubrick’s first big picture, a well-made crime documentary of a track robbery timed to coincide with a long horse race. Kubrick rewrote Lionel White’s Clean Break as a screenplay. Kubrick’s screenplay is tighter than White’s novel. The Killing, unlike the novel, begins and ends on a Saturday. It introduces each character as a piece in a temporal jigsaw puzzle and c oncludes one week later by showing how these separate human elements come together in time and space to execute Johnny Clay’s “foolproof” robbery plan. Beginning with the credits, the film builds on a structure of simultaneity and repetition, leading up to the race. Kubrick gives the race itself an importance not found in the novel. When the actual robbery sequences begin, Kubrick and his editor, Betty Steinberg, have a field day. The scheme for the killing is complex, and six different people must fulfill various duties precisely on schedule. Thus, the cutting back and forth, and the jumping forward and backward in time become rather complicated. The film was hailed, in its time, as being rather innovative, and Kubrick comes through with a sophistication which belies his years and relative inexperience.

The Killing was made for $320,000, a very low budget by Hollywood standards, even in 1955. Kubrick was able to get, for the first time, professional actors and a full professional crew. Because of this, Sterling Hayden was signed on as the lead. His most notable film before this was The Asphalt Jungle (1950), which superficially resembles The Killing as another “caper” film. Hayden’s performances in both are very close. The Killing was shot entirely on film sets, except for scenes at the race-track and the airport. The largest set used was the race-track betting area, yet the film’s air of total realism transfigures it. Now that his film had a conventional Hollywood status, union regulations prevented Kubrick from doing the photography himself, and this led to a certain tension when his cameraman objected to panning or tracking shots involving a twenty-five millimetre lens, fearing that distortion would result. (The lens was the widest available in 1956; now directors use even nine-millimetre lenses!) The confidence that he gained from his previous work paid off: the tracking shots were perfectly realised using the twenty-five millimetre lens. Though he was working for a major studio, Kubrick was able to maintain full artistic control. Many consider The Killing the real start of Kubrick’s career. It was filmed on a small scale, and unlike most of Kubrick’s other works it is intended mainly as an entertainment. Nonetheless, the director shows us things which we will see more of as we watch his later films.

Bibliography: Kubrick: The Films ofStanley Kubrick by Daniel Devries, 1973;

The Cinema of Stanley Kubrick by Norman Kagan, 1972;

Kubrick: Inside a Film Artist’s Maze by Thomas Nelson, 1982;

Stanley Kubrick Directs by Alexander Walker, 1971.

Notes by Fred Cohen

Leave a Reply