Leave Her to Heaven (1945)

Production Company: 20th Century Fox. Producer: William A. Bacher. Director: John M. Stahl. Screenplay: Jo Swerling, based on the novel by Ben Ames Williams. Music: Alfred Newman. Orchestrations: Edward Powell. Art Directors: Lyle Wheeler, Maurice Ransford. Cinematographer: Leon Shamroy. Special Effects: Fred Sersen. Editor: James B. Clark. Set Decorations: Thomas Little, Ernest Lansing. Costumes: Kay Nelson.

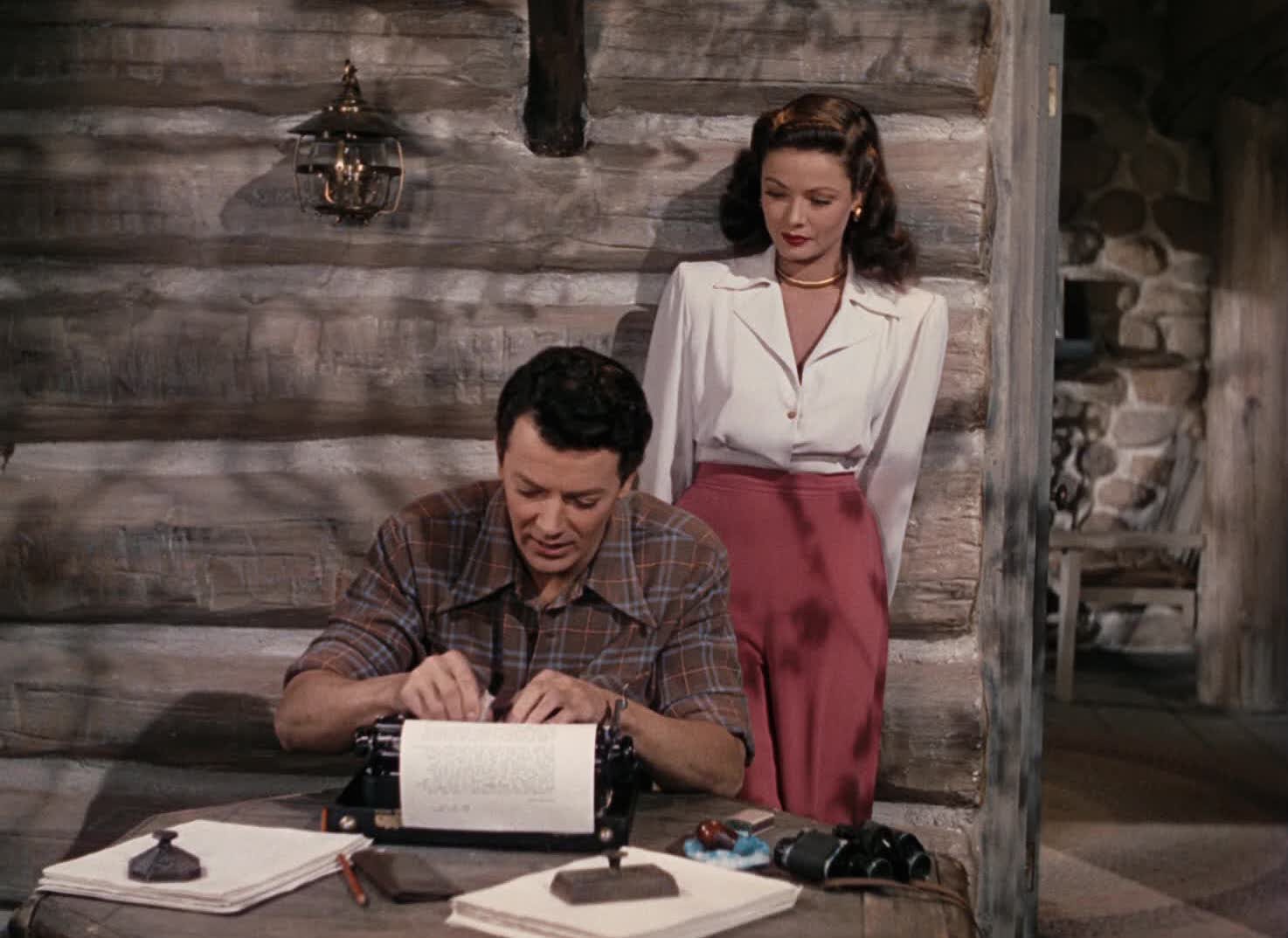

Cast: Gene Tierney (Ellen Berent), Cornel Wilde (Richard Harland), Jeanne Crain (Ruth Berent), Vincent Price (Russell Quinton), Mary Phillips (Mrs. Berent), Ray Collins (Glen Robie), Gene Lockhart (Dr. Saunders), Reed Hadley (Dr. Mason), Darryl Hickman (Danny Harland), Chill Wills (Leick Thorne), Paul Everton (Judge), Olive Blakeney (Mrs. Robie), Addison Richards (Bedford), Harry Depp (Catterson), Grant Mitchell (Carlson), Milton Parsons (Medcraft), Betty Hannon (Tess Robie), Mae Marsh (Fisherwoman), Earl Schenck (Norton), Hugh Maguire (Lin Robie), Kay Riley (Nurse).

After evil professors, psychotic killers, eerily sinister politicos and the like, none could be more bizarrely malevolent to round off our “Villainy” series than Gene Tierney in Leave Her To Heaven. In a part few actresses could resisst, Tierney is quite fascinating as the insanely jealous Ellen. In her own Self Portrait, Gene Tierney recalls: “The role was a plum, the kind of character Bette Davis might have played, that of a bitchy woman. I don’t think I have such a nature, but few actresses can resist playing bitchy women. I quickly told Zanuck that he would never regret it if he gave me the part. In a few days he called back and said simply, ‘You’re Ellen.'” (The part brought her her only Academy Award nomination; she lost her chance at an Oscar due to Joan Crawford’s brilliant portrayal of Mildred Pierce.)

Leave Her To Heaven, seen in reviews of the time as a lushly-photographed “femme” picture, provides a portrait of morbid selfishness enhanced by outstanding photographic effects. The resulting overall impression of the direction and colour photography led the authors of The Motion Picture Guide (Jay Robert Nash & Stanley Ralph Ross) to qualify Leave Her To Heaven as film noir: “…film noir is dictated by the script and character development, not the technical process…”. John M. Stahl, whose work is often considered a prelude to Douglas Sirk’s remakes (Sirk remade Imitation of Life, 1959, Magnificent Obsession, 1954 and Interlude–his version in 1957 of Stahl’s 1939 film When Tomorrow Comes), has been re-appraised since his death in 1950 to the extent that Richard Roud, in Cinema: A Critical Dictionary, vol. 2, claims that at his best, Stahl was better than Sirk. In the 1930s, Stahl made his reputation by directing leading ladies in what The Illustrated Guide to Film Directors‘ author David Quinlan calls “four handkerchief weepies of epic structure”. Among his best were Back Street (1939), starring Irene Dunne; Only Yesterday (1933) starring Margaret Sullavan; and Imitation of Life (1934) with Claudette Colbert. Holy Matrimony (1944) was rathr unique in Stahl’s oeuvre, combining as it did the talents of Monty Woolley and Gracie Fields in one of the few comedies he ever directed. While comparisons to Sirk’s distinctive style see Stahl as being more restrained and stylized, rather than stylish, Leave Her To Heaven represents something of a departure for Stahl, where he can pull out all the stops in his first colour film. After Heaven, Stahl was approaching the end of his career and, indeed, made only three more films before his death.

The story of a woman so bound by an incestuous link to her dead father that she is entirely controlled by her attachment to a man who resembles him follows her murderous plotting from drowning to suicide with moody fascination. Yann Tobin, in American Directors, vol. 1, praises Stahl’s depiction of one of society’s misfits:

“Cool, discreet, muted, the direction of Leave Her To Heaven is marked by the occasional typically Stahlian lyrical outburst, transcended by the lush Technicolor photography (which won Leon Shamroy a deserved Academy Award). The striking use of background and space, especially in the outdoor locations, assists in the drama’s progression.” (p. 299)

Gene Tierney, fresh from her success portraying the beautiful, enigmatic figure of Laura in Otto Preminger’s Laura, rose to the challenge of playing a character who is more than just a pretty face. Not surprisingly, one of the most strikingly lovely of the 40’s actresses had often been cast in such roles. Nor is it surprising that the reviews of Leave Her To Heaven failed to see beyond the attractive exterior to Tierney’s interpretation of the emotionally disturbed Ellen. The New York Times review (Dec. 26, 1945) was particularly vituperative: “Tierney’s petulant performance of this vixenish character is about as analytical as a piece of pin-up poster art”. The luckless Jeanne Crain, as Ellen’s sister, fared no better (“colorless and wooden”), especially as she had been hauled over the coals earlier that year for her performance in State Fair which was generally panned, despite the Rodgers and Hammerstein/Walter Lang collaboration. Cornel Wilde, as the wimpish, over-powered husband, had trouble with his role after playing the forceful Chopin in A Song To Remember in the same year. All of the supporting cast, Mary Philips as the mother, Darryl Hickman as the younger brother, Gene Lockhart in a brief role, and Ray Collins as the family attorney, were praised for their performances; except, perhaps, Vincent Price whose role as the discarded lover/district attorney gave him plenty of scope for an over-theatrical performance.

The emotional power of the jealousy theme is generally well-served by the elaborate set decoration and the on-location shooting (in Arizona and northern California), and together with the spectacular colour photography provide a superbly tranquil backdrop to the investigation of the progressive horrors of the disintegrating mind. Perhaps too superbly done, the background elements were in fact seen by some critics as the most accomplished facets of the film, to the detriment of the human elements of the story, which is seen to dissolve rapidly into improbability and annoyance.

But, as the images of Gene Tierney, with blood-red lips, spreading her father’s ashes to the wind, and choosing the right lipstick with cold-blooded deliberateness before throwing herself downstairs, begin to fade, we recall the words of David Quinlan (The Illustrated Guide to Film Directors, p. 282): “For records of how emotional impulses can dominate and change lives, his (Stahl’s) films have few equals”.

Notes by Geraldine V. Koohtow

Leave a Reply