Troubled Waters (1936) and School for Scoundrels (1960)

Toronto Film Society presented Troubled Waters (1936) on Monday, September 19, 1988 in a double bill with School for Scoundrels (1960) as part of the Season 41 Monday Evening Film Buffs Series “C”, Programme 1.

Troubled Waters (1936)

Production Company: Fox British. Producer: John Findlay. Director: Albert Parker. Screenplay: Gerard Fairlie, from story by W.P. Lipscomb and Reginald Pound. Photography: Roy Kellino.

Cast: Virginia Cherrill (June Elkhardt), James Mason (John Merriman), Alastair Sim (Mac MacTavish), Raymond Lovell (Carter), Bellenden Powell (Dr. Garthwaite), Sam Wilkinson (Lightning), Peter Popp (Timothy Golightly), William T. Ellwanger (Ezra Elkhardt).

School for Scoundrels (1960)

Production Company: ABP (Guardsman). Producer: Hal E. Chester. Director: Robert Hamer. Screenplay: Patricia Moyes, Hal E. Chester, Peter Ustinov, from books by Stephen Potter. Photography: Erwin Hillier. Music: John Addison.

Cast: Ian Carmichael (Henry Palfrey), Terry-Thomas (Raymond Delauney), Janette Scott (April Smith), Alastair Sim (Stephen Potter), Dennis Price (Dunstan Dorchester), Edward Chapman (Gloatbridge), Kynaston Reeves (General), Irene Handl (Mrs. Stringer), John le Mesurier (Skinner), Hugh Paddick (Cogg Willoughby), Peter Jones (Dudley Dorchester), Gerald Campion (Proudfoot), Hattie Jacques (Mrs. Grimmett), Anita Sharp Bolster (Alice).

This first programme in our British series derives from the request of a member for a series of films featuring Alastair Sim. Since over the years we have shown most of his major pictures, including, most recently, The Doctor’s Dilemma last season, we settled for a double bill honouring this splendid comedian, and representing both his apprentice and mature work. (As a bonus, you will see him again in our second programme).

Alastair Sim reminds us, perhaps of the American Monty Woolley, the scholar-practitioner in the theatre and the cinema, though he was a better actor, and no less of a personality, than Woolley. He was a Scot, born in Edinburgh in 1900, who graduated from the great university in his native city, and went on to be a lecturer in elocution at New College from 1925 to 1930. Later, from 1948 to 1951, he was rector of the University, and received an honorary doctorate in 1953. In the years between, he had become a star of the stage and screen. He first appeared on the London stage in 1930, n”Othello”; and he subsequently played many Shakespearean roles, as well as producing–for he proved a good businessman–a number of West End hits, often with himself in the leading role. One of his favourite parts, which he played many times after 1941, was that of Captain Hook in “Peter Pan”.

But it was his film career that brought him his greatest fame–and even a CBE, in 1953–and this began in 1934 in Riverside Murders. This first picture set the keynote of his work before the war, when his successes were chiefly fairly-quickie mystery thrillers (This Man is News); he showed to special advantage in the Inspector Hornleigh trio of film, in which he easily held his own, as Sergeant Bingham, with Gordon Harker in the title roles. After the war came his finest hour, beginning with that taut little detective story Green For Danger, in which he acted Christianna Brand’s Inspector Cockrill, and Hue and Cry, the first of the great Ealing comedies, in which he played a seedy writer of comic books who signalled criminal blueprints through his cartoons. Then came a handful of still greater performances: as the harassed headmaster with a girls’ school billetted on him by a bureaucratic error, in The Happiest Days of Your Life; as the ne’er-do-well recipient of a bequest in Laughter in Paradise; as the definitive Scrooge, still and forever visible on our television screens each Christmas; as the long-suffering padre, organizing against all odds a military camp concert, in Folly to Be Wise; as the eponymous supernatural visitor of An Inspector Calls; and as the devilish but inept assassin by bomb-plot of The Green Man, to be shown later this season in our “Villainy” series.

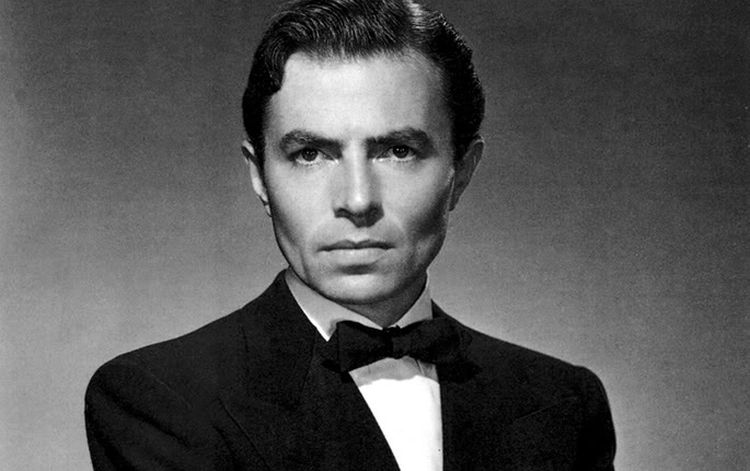

From this wonderful array of roles we have selected two to suggest his range in both acting scope and time. Troubled Waters was only his fifth picture, in his second year before the cameras (it was James Mason’s third picture, as well as the tenth, and last, for Virginia Cherrill, whose first film role had been as the blind girl in City Lights). The film itself is of little other intrinsic interest, except in the typically British whimsy it sets on display: a man is killed in a village car crash, and the villagers set it up as a murder to publicize their home-grown mineral water. It is indeed a murder, however, but there is also the matter of explosive smuggling, and a further oiling of the waters in the villagers’ second enterprise, liquid explosives. Sim plays a rascally Scot, the villain of the piece, and does it with the same kind of facial gesture–to convey a myriad emotions–that marked his entire career.

By the time of School for Scoundrels, Sim’s best work was done, and this was his sixth-last picture, to be followed by another Shaw adaptation (The Millionairess), and, his last film, for Disney, Escape From the Dark. (School for Scoundrels remains a worthy representative of his later manner. In the 1950s Stephen Potter had written a number of semi-serious works, most notably Gamesmanship, which hymned, not wholly tongue in cheek, the virtues of what Sim (as Potter) succinctly expresses in the film as “he who is not one up, is one down.” (Potter added the word oneupmanship to the language: what we would now call assertiveness training, with more than a touch of bluff and duplicity.

Poor Henry Palfrey is beaten at tennis, love, and everything else, by the ebullient and self-confident (and as usual gap-toothed, fruity-voiced) Raymond Delauney (Terry-Thomas): the lovely April is the principal object of their rivalry. Henry is the unpromising material that this potter must take in hand and mould into a model of self-assertiveness. He must transform a wimp into the victor over his more bombastic and aggressive antagonist. Henry is played by Ian Carmichael, the put-upon of Private’s Progress, the quintessence of the English silly ass, Bertie Wooster himself, before he graduated through Lucky Jim to the ultimate, but presumably respectable, English silly ass, in Lord Peter Wimsey. Sim performs his task of making a successful oneupman out of this s.a., and does so with characteristic aplomb. But this older Sim is more cynical, worldly weary, than he had been, perhaps because his Potterian self-confidence leaves him in no doubt as to the outcome (as Scrooge, the padre, or the headmistress at St. Trinian’s were often in doubt). In School for Scoundrels, as nowhere better, Sim exhibits what the New York Times at his death in 1976 called “a velvet voice, a droll with and the face of a cunning bloodhound.”

Like many great virtuoso players, Alastair Sim usually made his films his own; Alfred Hitchcock didn’t give him much to do in what was an inferior picture for both of them, Stage Fright. he is an actor-auteur, for who can remember who directed A Christmas Carol? And his fame is certainly more secure than the directors’ of two of his masterpieces–Robert Day’s or Mario Zampari’s–or Albert Parker’s. While some of his best films were made under the solid, often distinguished direction of Sidney Gilliatt or Frank Launder, Sim’s is the name on the marquee of history. In School For Scoundrels, however, he did have a great director to work with: it was the tenth and last feature for Robert Hamer, who had made a decade earlier the most literate, the wittiest, and perhaps the greatest of Brisith screen comedies, Kind Hearts and Coronets. Two of Hamer’s films, Pink String and Sealing Wax and Father Brown, Detective, illustrate his penchant for grim thrillers with perhaps an undercurrent of sometimes bitter comedy; the characteristic grimness emerges in School For Scoundrels, despite the comic surface, as not so indulgent cynicism. Perhaps this is more Hamer’s film than Sim’s. In any case, it was close to the end for both of them, and Hamer’s death in 1963 at the age of fifty-two was a major loss to the British cinema.

Though this is Alastair Sim’s night, finally, we should salute some of his co-workers on these two pictures: a very young James Mason is of considerable interest, as is Raymond Lovell, almost as young, the Canadian-born actor who later made a minor mark in 49th Parallel and Caesar and Cleopatra; and the screenwriter for Troubled Waters is Gerard Fairlie who was both the model for Sapper’s Bulldog Drummond and the writer of the Drummond novels after Sapper’s death; he scripted also several of the Drummond films, including Calling Bulldog Drummond, which is the last picture in this series. And School for Scoundrels is a very repertory company of British character actors: let us just mention Kynaston Reeves, the Lord Chief Justice in this summer’s The Winslow Boy, Hattie Jacques, already entangled in the egregious Carry On series, and John Le Mesurier, one of the most underrated of British second bananas, a headwaiter whose ears bristle at the sound of rustling banknotes.

If Alastair Sim’s extraordinarily varied performances have a feature in common, it is that great mask of long suffering that he wears–it may be cynical, bored, harassed, but it is always, beneath the variations, his own. To mention his peers and near-peers, he is never a buffoon, as Arthur Askey is; he is never obtuse, and fortuitously triumphant, as Will Hay often is; he is never merely obstinate and impassive, as Gordon Harker sometimes is. He is, at a level of literacy and wit above all of these, the best and the subtlest comedian of the British screen between 1940 and 1960.

Notes by Barrie Hayne

Leave a Reply