October [Ten Days That Shook the World] (1927-28)

Toronto Film Society presented October [Ten Days That Shook the World] (1927-28) on Monday, April 25, 1960 as part of the Season 12 Monday Evening Silent Film Series, Programme 6.

Chaplin and Eisenstein

Although their styles are about as different as possible, it does not seem inappropriate to present the work of Charles Spencer Chaplin and Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein on the same programme. Both are acknowledged masters of the cinema; both ran afoul of official opinion in the respective countries where they did most of their film work; both made belated and reluctant, but successful, adjustments to the sound medium; the two men knew and admired one another (Chaplin was one of Eisenstein’s better friends during his sojourn in the United States).

Tonight’s programme will open with The Floorwalker (USA 1916), one of Chaplin’s famous Mutual comedies, written and directed of course by himself, with Edna Purviance, Eric Campbell, Lloyd Bacon, Albert Austin, Charlotte Mineau, Leo White.

October [Ten Days That Shook the World] (USSR 1927-28). Production: Sovkino. Direction and Scenario: S.M. Eisenstein, G.V. Alexandrov. Assistant Direction: Ilya Trauberg, M. Shtraukh, M. Gomorov. Photography: Eduard Tissse. Design: Kovrigin.

My first glimpse of Eisenstein’s work came many years ago at a time when my hometown of Winnipeg was innocent of all such films. I had heard a wild rumor that Ten Days That Shook the World was to be screened in a little hall on North Main Street, that once had served the Winnipeg Little Theatre–but evidently Other Interests had bought or rented it, for upon enquiry at the door I was told that the film was not showing tonight, but tomorrow night–Tim Buck was speaking tonight! So back I came the next evening, and sure enough Ten Days was unreeled. It seemed very far to the tiny screen (could it have been smaller than 16mm.?) and instead of musical accompaniment we were treated to a “live” running commentary (by Tim Buck? who knows!) that reached some sort of climax with the pronouncement that “the bourgeois lady hits the poor Bolshevik with her parasol.” Despite the unhappy presentation, something of the art and excitement of a great director did come through–but it was not until after World War II that I was able to view this and kindred films with a proper degree of appreciation.

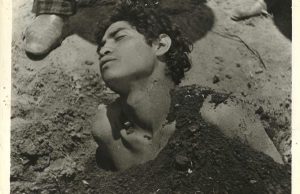

Eisenstein said of the making of this film: “In October the big crowd scenes were almost entirely played by workers who appeared by their own choice, for no payment. When we filmed the attack on the Winter Palace, two or three thousand workers came every day or night and offered to take part in the scenes we needed. The shooting in the street was entirely played by volunteers: nearly all were men who in 1917 had taken part in the same action to much grimmer purpose–if an actor, to play the part of an old man, needs a day or two to prepare himself to enact the role and rehearse it, an old man has had 60 years in which to perfect his characterization–one should choose from a crowd those faces, expressions and types that one needs and which correspond to the ideas one has preconceived, and discover among these living human beings the characteristic types which shape movie imagination. We must plunge into life itself.

Critical Comment on October:

Museum of Modern Art Film Notes: “Planned as part of the tenth anniversary celebrations of the October Revolution of 1917, but completed only in 1928, this film recalls events in St. Petersburg from February to November 1917. It is the purest example of what Eisenstein calls ‘ideological montage’. The subject matter is not treated as history–there are obvious omissions and distortions–but in the manner of a political cartoon. The fact that events were re-enacted in the actual settings, with crowds who may well have participated in them 10 years before, gives the picture a force which the impact of its deliberate construction greatly enhances. The raising of the bridge, one of the most famous sequences in film history, is certainly the one in which the dimension of time is most stretched. Not a document but a tract, Ten Days is a classic example of the editorial manipulation of material for emotional effect.

Paul Rotha in The Film Till Now: “It undertook the selection and presentation of actual events and persons, not for accurate historical description, but for the expression of a definite political viewpoint–hence the omission of Trotsky. Not only the simple forms of dramatic construction but the subtler observations of irony and caricature were employed, to persuade the spectator toward the desired acceptance of the facts. Eisenstein builds with a remarkable process of cutting, an overlapping of movement from one shot into the next that filmically gives double strength to his images. The raising of the bridge in Ten Days, with the dead horse and the girl’s hair as details, was so overlapped and shot from every available angle that the actual movement was synthesized into at least a dozen filmic movements. It is the insistence so produced that gives his work such extraordinary strength. I find it hard to believe that any audience exists in any cinema which would not react to the double-exposed, interrupted cutting of the machine-gun sequence in Ten Days. The reaction, however, would not be caused only bythe dramatic value of the machine gun and the scattering crowd, but by the cinematic treatment of the incident.”

Lewis Jacobs in The Rise of the American Film: “A dramatization of the ten days following the establishment of the Kerensky provisional government; it appeared so real that many claimed its shots were actual newsreels of the period. Like Potemkin it had no hero save the revolutionary masses, and its basic structural principle was movement; but instead of centering about a single event it dealt with a series of events. It is Eisenstein’s most complex effort. Its structure is so closely knit that the film is impossible to analyze at one viewing. Shots are blended with each other with such amazing dexterity–with such intuition for the precise image, the exact pace, the best psychological angle, the perfect fluidity–that they are overwhelming. Truly a great director’s picture.” Jacobs then analyzes in some detail the drawbridge episode, “perhaps the most forceful example of Eisenstein’s use of intra-scene cutting for dramatic impact”, in which he claims the director deliberately “destroys all sense of real time” to create the desired emotional suspense. Jacobs also points out Eisenstein’s satirical visual references to Caesar and Napoleon in his treatment of Kerensky.

Bardeche & Brasillach in History of Film: “October did not attain the same force or conciseness as Potemkin. It contains some magnificent scenes–which prove that Eisenstein is always a master of imagery; but the brevity of Potemkin imposed an admirable contraction upon its maker, while October, larger and more ambitious, loses itself in details and seems confused.”

Marie Seton, Eisenstein’s biographer, points out that he intended to use film montage to express not only emotional feelings but intellectual concepts which he was sure audiences would grasp–but she says: “October was an esoteric work of art permeated with symbols of ambiguous meaning to the majority–a work on several levels all developing simultaneously. An encyclopedia of images, it rose to a crescendo that could leave many spectators exhausted by the mental gymnastics required to follow the discursive line”.

Notes by George G. Patterson

_______________________________________________________________________

The following features were shown in the Silent Series this season. After the showing, please check the title(s) you liked most, and leave sheet with us, or mail to me (G.G. Patterson, 10 Bowden Street, Toronto). Thanks!

The Fall of the House of Usher. The Strong Man. The Birth of a Nation. Moana. Nanook of the North. The Joyless Street. Ten Days That Shook the World [October].

Leave a Reply