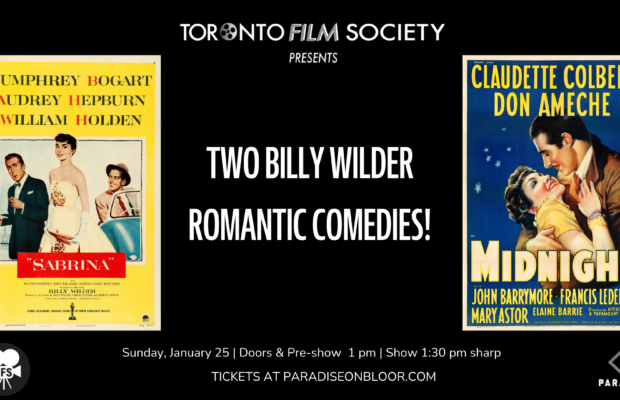

Sabrina (1954) and Midnight (1939)

By Toronto Film Society on January 25, 2026

Toronto Film Society presented Sabrina (1954) on Sunday, January 25, 2026 in a double bill with Midnight (1939) as part of the Season 78 Series, Programme 3.

SABRINA (1954)

Production Company: Paramount. Producer: Billy Wilder. Director: Billy Wilder. Screenplay: Billy Wilder, Samuel Taylor, Ernest Lehman, based on the play Sabrina Fair by Samuel Taylor. Director of Photography: Charles Lang, Jr. Editor: Arthur Schmidt. Art Directors: Hal Pereira, Walter Tyler. Set Decorators: Sam Comer, Ray Moyer. Music: Frederick Hollander. Songs: “Sabrina” (Wilson Stone); “Isn’t It Romantic” (Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart). Running time: 113 minutes. The film premiered in Toronto on September 1, 1954 and was released on September 23, 1954 in New York and Los Angeles.

Cast: Humphrey Bogart (Linus Larrabee), Audrey Hepburn (Sabrina Fairchild), William Holden (David Larrabee), John Williams (Thomas Fairchild), Walter Hampden (Oliver Larrabee), Martha Hyer (Elizabeth Tyson), Joan Vohs (Gretchen van Horn), Marcel Dalio (Baron), Marcel Hillaire (Professor), Nella Walker (Maude Larrabee), Francis X. Bushman (Mr. Tyson), Ellen Corby (Miss McCardle).

Billy Wilder in 1954 was turning away from his dark, uneasy masterpieces of the previous decade (Double Indemnity, A Foreign Affair, Sunset Boulevard), and pointing towards his more salubrious comedies of the next five years (The Seven Year Itch, Some Like It Hot). Sabrina is his most charming film, the one in which he comes closest to telling a fairy tale. The films Wilder had made with other directors were often Märchen–Hawk’s Ball of Fire, and the remake A Song is Born, versions of Snow White, Lubitsch’s Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife and Ninotchka, Mitchell Leisen’s Midnight, a version of Cinderella. But none of these quite maintained the fairy-tale tone as well as the structure throughout.

Like his master Lubitsch, Wilder customarily introduces his films with a narrative voice, via either a written title or the voice itself over; here it actually begins, “Once upon a time,” and invokes a world of charm and ease where everyone has his place on a preordained chain of being, down to the goldfish called George. The bridge from this graceful illusion to the only slightly more harsh reality of the film is made through the memorable vertical pan downward from the painting of the Larrabee family to the family itself, older, but in the very same poses: the dignified but still skittish Oliver, the matriarchal Maude, the solid, stolid Linus, the playboy David–all characterized by simultaneous word and image. But the basic fairy-tale quality remains unchanged, for what could be more romantic (even if “Isn’t It Romantic” were not there to remind us) than the scenes in the indoor tennis court, with Bogart’s feet approaching the waiting heroine: the prince disguised as the prime minister disguised as the prince. A world where sexuality is no more than the dropping of a tennis net, and where life is seen through tinted glasses, in Paris as in Long Island–La Vie en Rose.

Sabrina is a fairy tale where the ugly duckling turns into a swan, where the princess transforms a frog into a prince through her love, and where, with a Wilderian turn of the screw, Cinderella finds her prince not by fitting herself to a glass slipper, but by fitting a fedora to him. Indeed, the film is much concerned with hats, using them as indices of growth or regression, or both: from the Paris hat Sabrina wears on her return from Europe, to David’s natty Panama and Linus’s college beanie, to the crucial fadeout moment; they are also badges of a rigid class system, like the Baron’s soft felt, or Fairchild’s chauffeur’s-cap. All this finds its justification in a world (to borrow another analogy the film uses) of comic operetta, a genre rich in costume and fancy headgear. It seems wholly appropriate that the King and Queen of Greece visited the set during the shooting, and were forthwith ensconced on studio thrones, with red-carpet runners.

To play his fairy-tale characters, Wilder chose suitable icons. For the Princess, Audrey Hepburn, who had just played such a one in her last film, Wyler’s Roman Holiday. For the False Prince Charming, William Holden, who had just played the playboy in The Moon Is Blue, and still carried with him the charming irresponsibility he had created for Wilder in Sunset Boulevard and Stalag 17. For the False Princess, the epitome of blonde vacuity, that Grace Kelly manque, Martha Hyer. For the Old Kinds, the marvellous Shakespearian Walter Hampden, and that no less marvellous hero-villain of the silents, Francis X. Bushman. For the Old King Disguised as Woodcutter, John Williams, the kindly but persistent dispenser of justice of Dial M For Murder. For the Fairy Godmother, that little gnome of Jean Renoir’s, Dalio.

Only the True Prince Charming presented problems. The part of Linus was intended for Cary Grant, who was unavailable. That Bogart felt himself to be second choice helped to make the relations between star and director the most explosive of Wilder’s career before his two pictures with Marilyn Monroe. Bogart referred to the film as “a crock of crap” (or “shit”–quotations of the remark vary, but the alliterative version is perhaps to be preferred), and to the director (actually a Jew), as “that Nazi.” Wilder’s characterization of Bogart as “a bore” (“You have to be much wittier to be mean”) was one of his milder statements on the actor. Nonetheless, Bogart as Linus is one of the real pleasures of the film, after one has thought one’s way through the icon. His sardonic playing (as Linus) from behind the lover’s persona is wonderfully balanced, especially in the boat scene where he introduces “Yes, We Have No Bananas” to the girl too young to remember it; the change from feigned lover to true lover is so subtly managed that one cannot identify the moment where it occurs. Is he serious when he tells her of his lost love of long ago, or is he still feigning? Is this Joe College with or without a touch of arthritis?

In adapting Samuel Taylor’s stage success to the screen, Wilder rewrote extensively, shifting the emphasis from the democratic idealism of the play (Ever poor girl can marry her millionaire) to a more genial acceptance of aristocratic, or plutocratic, values. But unlike his next film, The Seven Year Itch, where the camera remains rather set-bound, save in the fantasy sequences, Sabrina is insistently cinematic, whether in the tracking towards the mansion in the narrative opening, in the montage of Sabrina’s stay in Paris, or of Linus’s courtship.

If Wilder’s openings are usually narrative, reminding us that he is telling us a “story,” it is noteworthy that many of his best films end in a journey begun, often by sea or air, as if the only way the characters can live happily ever after were by leaving earthbound things behind them. As the great liner leaves the docks of New York, the fairy tale continues.

Notes by Barrie Hayne

MIDNIGHT (1939)

Production Company: Paramount Pictures. Producer: Arthur Hornblow, Jr. Director: Mitchell Leisen. Screenplay: Charles Brackett and Billy Wilder based on a story by Edwin Justus Mayer and Franz Schulz. Cinematography: Charles Lang. Film Editor: Doane Harrison. Music: Frederick Hollander. Release Date: March 24, 1939. Running time: 94 minutes.

Cast: Claudette Colbert (Eve Peabody), Don Ameche (Tibor Czerny), John Barrymore (Georges Flammarion), Francis Lederer (Jacques Picot), Mary Astor (Helene Flammarion), Elaine Barrie (Simone), Hedda Hopper (Stephanie).

Midnight follows Eve Peabody, a penniless American showgirl who arrives in Paris with nothing but a gown, a knack for improvisation, and a talent for bluffing her way into high society. After passing herself off as a wealthy Hungarian baroness, Eve is swept into a world of aristocrats, con artists, and romantic entanglements, becoming an unwitting pawn in an elaborate scheme to manipulate a jealous husband. As lies pile up and identities unravel, Midnight delivers a breathless cascade of witty dialogue, farcical misunderstandings, and romantic reversals – a quintessential screwball comedy driven by speed, charm, and social satire.

Released in 1939 – generally acknowledged as the peak of Hollywood’s Golden Age, Midnight could have easily been shadowed, but it was a critical and box office success.

Billy Wilder and Charles Brackett started working together in 1936 and collaborated on thirteen feature films; a 1948 New York Times article tongue-in-cheek reported that they were “the happiest couple in Hollywood” – an unlikely working partnership of a Harvard-educated WASP and an Austrian immigrant born of hardworking Jewish parents. Just like the elites in Midnight, Brackett was an American Aristocrat, while Wilder (like the hard-work cab driver, Tibor) was stubborn, volatile, passionate. Wilder was also a notorious womanizer or, as Brackett called him, “the compleat amorist” – alluding to the 1906 romance novel, The Incomplete Amorist by Edith Nesbitt. Volatile and intense, Wilder would pace about with a riding crop while working. In his autobiography, Brackett described their creative process: “The thing to do was suggest an idea, have it torn apart and despised. In a few days it would be apt to turn up, slightly changed, as Wilder’s idea. Once I got adjusted to that way of working, our lives were simpler.” Not limited to comedy, this dynamic duo created great dark works including, The Lost Weekend (“One drink’s too many and a hundred’s not enough.”), Double Indemnity (“I killed him for money—and a woman.”), and their last collaboration, Sunset Boulevard (“I am big. It’s the pictures that got small” and “All right, Mr. DeMille, I’m ready for my close-up”).

Midnight was directed by Mitchell Leisen, someone known to be…shall we say…flamboyant, and whom Billy Wilder openly disliked, so much so that Wilder credited Leisen for driving him to keep creative control of his work by directing his own pictures. Wilder despised Leisen’s cuts and changes to the scripts. Actually, Preston Sturges had the same complaint about Leisen and didn’t like him either, calling Leisen merely an “interior decorator who couldn’t direct” and a “bloated phony” (see TFS notes on Easy Living).

“Don’t forget, every Cinderella has her midnight.”

Claudette Colbert stars as Eve Peabody, a beautiful but penniless Cinderella pretending to fit into high society; Don Ameche is her handsome, working-class prince and John Barrymore is Eve’s benevolent Godfather. Ms. Colbert was truly a beautiful Cinderella in gowns by ‘Irene’ — Irene Lentz, one of Hollywood’s greatest costume designers (see TFS Notes on Midnight Lace for more on Irene and her tragic death.)

In the movie, John Barrymore and Mary Astor elegantly play husband and wife social elites, Georges and Helene Flammarion. A bit about Mary: born in 1906 as Lucile Vasconcellos Langhanke, studio executives gave Mary Astor her stage name, evoking the sophisticated, high-society cachet of the Astor family. However, dear Mary was of humble origins, born in Quincy, Illinois; her parents were teachers. Alas, the lovely Mary Astor is no relation to the uber-wealthy Astor family; she was an Astor not.

Barrymore and Mary Astor first met on Beau Brummell (1924) when sweet Mary was a mere 17-18 year old ingénue. Beau Brummell is notable as both Mary’s first major film role and her scandalous love affair with Barrymore, a 40-year-old superstar with a reputation as a “philandering alcoholic.”

On the set of Midnight, Elaine Barrie appeared as Simone, the haute couture hat designer – and was also John Barrymore’s wife in real life. Despite this, there were lingering feelings between Barrymore and his former lover Mary Astor, who played his on-screen wife. In her memoir My Story, Astor recalls a quiet moment off-camera when she reached for Barrymore’s hand, only for him to pull away sharply, whispering, “Don’t… my wife is very jealous.”

Barrie herself had once been an ardent Barrymore superfan, eventually marrying her idol in 1936. Their volatile relationship mirrored the emotional instability Barrymore so often brought to the screen. The uneasy personal dynamics surrounding Midnight lend an added layer of poignancy to its elegant comedy of manners, where desire, deception, and social performance are always just beneath the surface.

1939 was also the year Canada set up the National Film Commission – later renamed the National Film Board of Canada (or the NFB, for short) – with John Grierson as its first Government Film Commissioner. A Scottish filmmaker brought in by the federal government, Grierson had strong ideas about what film could (and should) do. He believed documentaries should pay attention to everyday life and help build social awareness, famously describing the NFB as the “eyes of Canada.” He even coined the term “documentary film,” and argued that cinema had a responsibility to challenge old ways of thinking and imagine something better. By 1945, shifting political winds and Cold War anxieties pushed Grierson out. There’s a great NFB documentary about this era – Shameless Propaganda.

Notes by Carol Whittaker and Bruce Whittaker

You may also like...

-

News

Thank You from TFS!

Toronto Film Society | July 21, 2025Our matinée on Sunday, August 17th – at the blessedly air conditioned Paradise Theatre – will conclude the Toronto Film Society’s 77th season! But take heart, as we’ll be...

Programming

Virtual Saturday Night at the Movies

Toronto Film Society | January 25, 2026Toronto Film Society will be screening Sabotage (1936) straight to your home on Saturday, February 28, 2026 at 7:30 p.m. (ET)! Directed by Alfred Hitchcock, starring Sylvia Sidney, Oscar...

-

Toronto Film Society | January 25, 2026

Toronto Film Society | January 25, 2026

-

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

-

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Donate to Toronto Film Society – We’re now a Registered Charity!

Copyright © 2017 Toronto Film Society.