Seven Days in May (1964)

Toronto Film Society presented Seven Days in May (1964) on Monday, January 17, 1983 in a double bill with The Snake Pit as part of the Season 35 Monday Evening Film Buffs Series “B”, Programme 5.

Production Company: Seven Arts and Joel Productions (released by Paramount). Producer: Edward Lewis. Director: John Frankenheimer. Screenplay: Rod Serling, from the novel by Fletcher Knebel and Charles W. Bailey II. Photography: Ellsworth Fredricks. Editor: Ferris Webster. Music: Jerry Goldsmith. Art Director: Cary Odell. Set Decorator: Edward Boyle. Assistant Director: Hal Polaire.

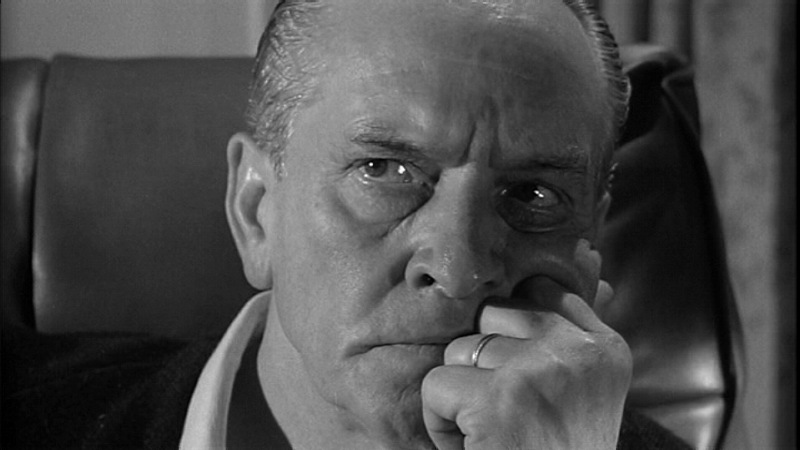

Cast: Burt Lancaster (Gen. James M. Scott), Kirk Douglas (Col. Martin Casey), Fredric March (Pres. Jordan Lyman), Ava Gardner (Eleanor Holbrook), Edmond O’Brien (Sen. Raymond Clark), Martin Balsam (Paul Girard), George Macready (Christopher Todd), Whit Bissell (Senator Prentice), Hugh Marlowe (Harold McPherson), Bart Burns (Arthur Corwin), Richard Anderson (Col. Murdock), Andrew Duggan (Col. “Mutt” Henderson), John Larkin, (Col. Broderick), John Houseman (Admiral Barnswell), Malcolm Atterbury, Helen Kleeb.

In John Frankenheimer’s Seven Days in May, it is not a psychiatrist who is called on to restore the confidence of the North American public, but none other than an imaginary 1970s President of the United States, played by Fredric March, as if to the White House born. The film presents the story of a United States Colonel (Kirk Douglas) who stumbles on an army plot to depose the President and assume power. The Colonel has only seven days to expose the plot and its originator (an Army General whom he had formerly respected).

We are led to believe that the General, played with to-billing by Burt Lancaster, was planning his coup d’etat in the best possible faith–from fear of the consequences of a nuclear disarmament treaty with Russia that the President had just signed. This feature of the plot allows March to make a stars-and-stripes forever speech, shifting some of the blame from the tarnished hero to global guilt: “The enemy is our age. A nuclear age. And out of this comes a sickness.” As one can imagine, critics cheered or jeered both this speech and the film depending on their own political persuasions. It was a box-office success, ranking 19th among the 1964 releases, and is, in the final analysis, a gripping political thriller.

Like The Snake Pit, Seven Days in May was adapted from a controversial contemporary novel. Director Frankenheimer came upon the material more or less by chance. Wishing to repeat the artistic freedom that, he felt, had led to the great success of The Manchurian Candidate (1962), he had just turned down a studio contract to film the Edith Piaf story (with Natalie Wood singing Piaf’s songs in English!), when an opportunity arose to ally himself with Kirk Douglas to produce Seven Days. Rod Serling, who had often worked with Frankenheimer in his live television days, was hired to write the script, and with bankable stars like Lancaster, Douglas and March, production backing wasn’t hard to find.

Frankenheimer has this to say about the film: “This was as important to me as The Manchurian Candidate. I felt that the voice of the military was much too strong. . . . We had just finished eight years with President Eisenhower, which were in my opinion a very discouraging eight years for the country. All kinds of factions were trying to take power. The film was the opportunity to illustrate what a tremendous force the military-industrial complex is.” (Quoted by Gerald Prately in The Cinema of John Frankenheimer, NY: A.S. Barnes, 1969)

Frankenheimer had, as a youth, been a mailboy in the Pentagon, and felt for this reason (among others) that he knew whereof his film spoke. He didn’t ask the Pentagon for co-operation in filming, because he knew he wouldn’t get it. Nevertheless, one day he had an unauthorized Kirk Douglas walk into the Pentagon in his Colonel’s uniform, where he was duly saluted by some unwitting officers. All the time, Douglas’s entrance and exit were being filmed by a camera covered by a black cloth in the back of a station wagon. (Eventually, these shots were found to be unnecessary for the film.)

At no time did the Pentagon express any reaction to filming the novel; but, as Frankenheimer informs us, Pierre Salinger’s personal helpfulness indirectly indicates President Kennedy’s tacit approval of the project: Kennedy apparently concurred with Salinger’s scheduling and was conveniently in Hyannisport at a time when Frankenheimer wished room to manoeuvre in shooting the White House scenes.

The early ’60s were years which saw a significant output of films shot in or about Washington. Comparisons inevitably arise between this film and Preminger’s Advice and Consent and Schaffner’s The Best Man. But the film that most strongly begs comparison is Kubrick’s genially quirky Dr. Strangelove, which was also released in 1964. The role of the military, the futuristic setting, and the threat to the government link the two films clearly. But the difference in directorial styles and political leanings produced two films that, each fine in its own way, seem to come from different planets.

One final note: critics of Seven Days in May were quick to weigh the relative merits of the lead performances by twice Oscared Fredric March, once-Oscared Burt Lancaster, and oft-nominated Kirk Douglas. But after all was said and done, it was Edmond O’Brien, doing a reprise of Charles Laughton’s southern senator in Advise and Consent, who was nominated for a (supporting) Oscar and won a Golden Globe award.

Notes by Cam Tolton

**********AN INFORMAL DISCUSSION OF THESE TWO FILMS**********

Tuesday, January 18, 1983, at 8:00 pm

Patio de Oro Building, 1430 Yonge Street

(second floor, corridor to left)

Please indicate your interest to any of the TFS directors

during the intermission.

Leave a Reply