The Sun Shines Bright (1953)

Toronto Film Society presented The Sun Shines Bright (1953) on Monday, March 22, 1976 in a Silent Series/Film Buff Special with The Grit of the Gilr Telegrapher (1912) and Paths to Paradise (1925) as part of the Season 28 Monday Evening Film Buff Series, Programme 5.

Production Company: Argosy Pictures-Republic. Producers: John Ford, Merian C. Cooper. Director: John Ford. Assistant Director: Wingate Smith. Scripts: Laurence Stallings, from the stories “The Sun Shines Bright, The Mob from Massac and The Lord Provides”, by Irvin S. Cobb. Photography: Archie Stout. Editor: Jack Murray. Assistant Editor: Barbara Ford. Art Direction: Frank Hotaling. Set Decoration: John McCarthy Jr., George Milo. Costumes: Adele Palmer. Music: Victor Young.

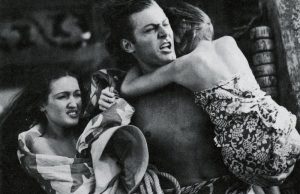

Cast: Charles Winninger (Judge William Pittman Priest), Stepin Fetchit (Jeff Poindexter), Arleen Whelan (Lucy Lee Lake), John Russell (Ashby Corwin), Russell Simpson (Dr. Lewt Lake), Ludwig Stossel (Herman Felsburg), Francis Ford (Feeney), Paul Hurst (Sgt. Jimmy Bagby), Mitchell Lewis (Sheriff Andy Redcliffe), Eve March (Mallie Cram), Grant Withers (Buck Ramsey), Milburn Stone (Horace K. Maydew), Dorothy Jordan (Lucy’s Mother), Elzie Emanuel (U.S. Grant Woodford), Henry O’Neill (Jody Habersham), Slim Pickens (Mink), James Kirkwood (General Fairfield), Mae Marsh (Old Lady at Ball), Jane Darwell (Amora Ratchitt), Ernest Whitman (Uncle Pleasant Woodford), Trevor Bardette (Rufe), Hal Baylor (His Son), Clarence Muse (Uncle Zack), Jack Pennick (Beaker), Patrick Wayne, Ken Williams.

Forty years have passed since the end of the Civil War, but the Confederate spirit, typified by the amiable, aging Judge Priest, still rules the town of Fairfield, Kentucky. It is election eve, and the Judge is up for re-election once again…

The Sun Shines Bright is the least revived of all John Ford feature films made after Stagecoach (1939). Production on the film was completed early in 1953 but it did not open in New York until the middle of March, 1954, and had already played in England almost a year earlier, in May of 1953. The film was frequently cut (once to sixty-five minutes) and often played the second half of double bills on its initial runs. The reason for this was that the film had no star or name players. Judge Priest, Charles Winninger (1884-1969), framed a career as a lovable supporting player; the rest of the cast was mainly comprised of a few old Ford stock company players such as Russell Simpson, Francis Ford, Jack Pennick, Jane Darwell and Mae Marsh. John Russell, the romantic ‘hero’, was at best a justifiably forgettable bit player, often in Westerns. His bland and rigid acting is a key weakness in The Sun Shines Bright. Another reason for the poor presentation and reception is the fact that Ford made this film not for the critics, not for the public, but for himself. Ford created The Sun Shines Bright for his own amusement, and consequently it is his own personal favourite film, the only one he liked to watch over and over.

Seldom has Ford made a more relaxed or less pretentious film than The Sun Shines Bright (it is interesting to note that Ford’s other favourite film, The Fugitive, is his most pretentious and ‘arty’ movie). The Sun Shines Bright is the one Ford film that needs the ‘auteur’ theory (one film of his cannot really be looked at as separate from the rest) more than any other. Many critics, viewing the film as a separate entity, tended to go along with Howard Thompson’s New York Times opinion: “…it would be harder to imagine a more laborious, pedantic and saccharine entertainment package.” Only Lindsay Anderson, first in the Monthly Film Bulletin (October 1953) and the in Sight And Sound (October-December 1953), placed The Sun Shines Bright in the context of Ford’s career as a whole. “The mellow, latter-day films of John Ford have an air of casualness and relaxation to them which, if it precludes the high poetic tension of his work of ten years back–The Grapes of Wrath, or Tobacco Road–is no less rich in feeling and artistry. The Sun Shines Bright is a film which follows directly in the line of his recent stories of America’s past; its mood is one of affectionate and humorous nostalgia, in which the human allegiances and faiths are as strong and refreshing as ever.”

“Ford made The Sun Shines Bright to please himself, and as a result it has all the mellowness and familiarity of one of his really personal films…With its homespun comedy of small-town snobberies and politics, its sentimental-humorous reminiscences of service in the lost cause of the South, its old-time songs and feudal atmosphere, The Sun Shines Bright is a film that Ford has enjoyed making all the way through…And personal feeling, personal statement–those qualities which seem each year to grow rarer in the American cinema–are implicit in every foot of it…It is impossible not to wonder at the way Ford has managed to preserve so freshly, all these years, this power to move and to delight, this poésie du coeur. The phrase is Cocteau’s; it evokes precisely the kind of positive poetry, full of faith and love of life, which Ford continues to create, alone.”

John Ford was never reluctant to repeat or borrow scenes and ‘set pieces’ from his own earlier films. Judge Priest’s dispersal of an angry lynch mob by reasoning with individuals in the group is remarkably similar to Abe Lincoln’s mob break-up in Young Mr. Lincoln (1939). Ford always repeated favourite musical tunes: the dance music in The Sun Shines Bright was prominently used in Young Mr. Lincoln. The formal military dance/march of Fort Apache (1948) appears again in The Sun Shines Bright. The tune “Dixie”, loved by Abe in Young Mr. Lincoln, figures strongly in The Sun Shines Bright. This repetition of ‘touches’ extended to Ford’s use of stereotype characters. And perhaps his preference for stereotypes continued into his employment of a regular stock company of actors and old cronies playing bit parts. He was familiar with what performers such as John Wayne, Ward Bond,Victor McLaglen, Maureen O’Hara, George O’Brien, Jane Darwell and Henry Fonda could do, and was thus able to begin his direction of these players from a point other directors would finish. Victor McLaglen and Barry Fitzgerald were his Irish ‘types’–Stepin Fetchit was one of his black stereotypes, the dumb but excitable black. It is intriguing to observe how far the reverse is true today–the super cool black stereotype in modern films is the complete antithesis of the Fetchit ‘type’. And as Film Quarterly put it, “Cooler second sight must admit that Stepin Fetchit was an artist, and that his art consisted precisely in mocking and caricaturing the white man’s vision of the black: his sly contortions, his surly and exaggerated subservience, can now be seen as a secret weapon in the long racial struggle.”

Though The Sun Shines Bright is not one of Ford’s best photographed films, there are still a few of the visual trademarks that made Ford the best in the business. There is a beautiful shot of Arleen Whelan looking through a window glass at her departing mother. While many of the interior scenes are quite ordinarily filmed, there are some, like the festival dance and the gathering of old army veterans in a meeting room, that rival the best Ford work. The funeral procession is flawlessly constructed and edited. And the final sequence, with Judge Priest standing outside his house watching the whole town parade by, is one of Ford’s greatest compositions.

The Sun Shines Bright is a much richer and more complex film than it first seems. The moral problems and solutions are simple enough, but Ford manages to diffuse this simplicity by spreading and intertwining the various plot elements to equal degrees. The film shuffles along imperceptively from courtroom proceedings, to old warrior reunions, to rape, to moralizing about children’s obligations to elders, to a lynch mob, to romance, to prostitution, to an illegitimate child, to a funeral, and to an election without pausing at one situation unduly. The narrative flows freely and it is easy to lose track of its direction. In this sense it’s probably more a strictly mood piece than any Ford film since Just Pals in 1920.

In Ford’s first version of the story (Judge Priest, filmed in 1934), Will Rogers played Billy Priest with greater charisma and originality than Winninger does in The Sun Shines Bright. Yet, Winninger’s characterization gains in gentle strength and poetic beauty as the film nears completion, and it is difficult to imagine Will Rogers evoking a comparative emotional quality and sincerity to Winninger’s in The Sun Shines Bright‘s concluding sequence.

Joseph McBride and Michael Wilmington (John Ford, Da Capo, 1975, New York) have some further comments on the film:

But what makes The Sun Shines Bright more powerful as a film [than Judge Priest] is the complex portrayal of the community of Fairfield, built up from many small moments of poetry and drama: the festival with its promenading cadets and girls who seem removed in time even as they go through their clock-like movements; the image of Judge Priest, faintly absurd in his white Southern gentleman’s outfit, as he stands outside the jail with Uncle Pleasant to await the mob; the old Confederates’ palsied rush into the courtroom when they hear the strains of ‘Dixie’; the majestic funeral procession, with the astonished populace falling in one by one behind the Judge and the carriage bearing the town whores; Jeff’s reflective harmonica commentary as the Judge and his cronies sit on the verandah lamenting the disruption of communal order. The Sun Shines Bright is like a précis of the Judge’s life, a testing and a summary of his ideas in a series of events which dovetail into each other with the uncanny symmetry of a dream. But the film finally seems less concerned with the Judge himself than with the community’s reaction to him. Rogers is the catalyst for most of what happens in Judge Priest; Winninger, on the other hand, is largely acted upon. It is a film about the last stand of honour and decency, and Ford’s casting of a roly-poly old vaudevillian in the role of the town’s noblest citizen is a beautiful touch, suggesting the frailty and perhaps even the anachronism of the principles he represents. The law, to Ford, is ot an impersonal system but a human instrument requiring delicate handling, and Judge Priest, to use Chesterton’s description of a judge in one of his Father Brown stories, is ‘one of those who are jeered at as humorous judges, but who are generally much more serious than the serious judges, for their levity comes from a living impatience of professional solemnity; while the serious judge is really filled with frivolity, because he is, filled with vanity’.

The twentieth century hangs over The Sun Shines Bright like a shroud. Like How Green Was My Valley, The Sun Shines Bright is a larger-than-llife, wide-eyed fanatas of past innocence, seen from the viewpoint of an old man looking back on a vanished society: there Huw Morgan looking back on his own childhood, here Ford looking back with the same ingenuous perspective which the Judge has in the ‘second childhood’ of old age.

By any standard of historical accuracy, Ford’s view of the Old South is rosy and unreal, and by contemporary standards, his solution to the racial problem is drastically limited by its overtone of paternalist condescension. The beauty of The Sun Shines Bright is in its innocence; the film is not a piece of historical documentation but one man’s fervent creation of a simpler, kindlier and more gentlemanly America than ever existed. Five years later, when Ford filmed another story of an old paternalist politician, The Last Hurrah, he bitterly echoed the finale of The Sun Shines Bright by having Mayor Skeffington walk home alone on the evening of his defeat, with his opponent’s victory parade marching in the opposite direction to the tune of ‘Hail, Hail, the Gang’s All Here’. Ford knew there is no room for a Judge Priest in modern America.

Notes by Jaan Salk

Leave a Reply