Pilgrimage (1933)

Toronto Film Society presented Pilgrimage (1933) on Monday, November 14, 2016 in a double bill with Sunday Dinner for a Solider as part of the Season 69 Monday Evening Film Buff Series, Programme 3.

Toronto Film Society presented Pilgrimage (1933) on Monday, July 26, 1982 in a double bill with To Each His Own as part of the Season 35 Summer Series, Programme 4.

Production Company: Fox Film Corporation. Director: John Ford. Screenplay: Philip Klein, Barry Connors, from the story “Gold Star Mother” by I.A.R. Wylie. Dialogue: Dudley Nichols. Photography: George Schneiderman. Art Direction: William Darling. Film Editor: Louis R. Loeffler. Music: R.H. Bassett, Louis de Francesco. Dialogue Director: William Collier, Sr. Release date: July 12.

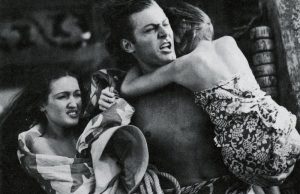

Cast: Henrietta Crosman (Hannah Jessop), Norman Foster (Jim Jessop), Heather Angel (Suzanne), Marian Nixon (Mary), Maurice Murphy (Gary Worth), Hedda Hopper (Mrs. Worth), Lucille Laverne (Mrs. Hatfield), Robert Warwick (Major), Charley Grapewin, Betty Blythe, Francis Ford, Louise Carter, Adele Watson.

Pilgrimage is the earliest film by John Ford that I have been able to see which I would call, with no hedging or qualifying, a masterpiece. It has not been an easy film to see, since it went into a limbo of non-distribution soon after its original release. This situation, as shared by most other films of the old Fox, was made prior to the merger with Zanuck’s Twentieth Century in 1935. As the majority of Ford’s earlier pictures had been made for Fox, much of his work has for far too long been impossible to see and study—not to mention enjoy. As in so many important rediscoveries, our amazingly resourceful TFS patron, William K. Everson, has helped to uncover early Fords more rewarding than Pilgrimage, which can be seen to anticipate The Informer (1935), The Hurricane (1937), and Young Mr. Lincoln (1939) in its humanity, its visual expressiveness, and its unpredictable explosions of almost raucous humour cheek-by-jowl with the most tender sentiment.

If the film, for all the Fordian fingerprints, literally looks somewhat different from most of this director’s later work, this may be for two main reasons. Firstly, he had been intelligently influenced by the extreme studio-controlled lighting and settings of the late Silent period, principally stemming from the German master F.W. Murnau’s Hollywood work (not coincidentally, at the same Fox studio). This awesomely dynamic and dramatic visual-narrative style eventually showed danger signs of overemphasis, and Ford favoured it less and less, except for specific individual scenes, after he turned from the doom-laden city of The Informer towards more open vistas in Stagecoach and his first Technicolor film, Drums Along the Mohawk, both in 1939. Secondly, Ford’s celebrated “stock company” of actors used face by face and stance by stance in similar roles, had not been established to a conspicuous extent as long ago as 1933.

In any event, on this latter point, the story would quite properly have needed to be dominated by the actress playing staunch but stubborn Hannah Jessop. The role is so rich that one wonders whether a more familiar film personality—Marie Dressler, Mae Marsh?—might ever have been held in mind. As it was, stage star Henrietta Crosman (1861-1944) was called to Hollywood from Broadway for what turned out to be her only lead role. A Fox contract let to a few other, mostly high-born roles in support of such as actors as Lionel Barrymore, in the late Henry King’s Carolina (1934), and you-know-who, in Charlie Chan’s Secret (1936). In fact, her last years were spent in partial retirement under the California sun. The wonderful Ms. Crosman approached her Indian Summer of the movies with an appropriately Fordian gratitude, combined with resignation, when she spoke briefly at Pilgrimage’s opening at the Gaiety in New York City. A little younger than her character of the film, but not much, she said simply: ‘My hair is growing white. If you like Hannah Jessop, you will make me the happiest woman in New York.”

Notes by Clive Denton

Leave a Reply