The Best Man (1964)

Toronto Film Society presented The Best Man (1964) on Sunday, October 16, 1988 in a double bill with Counsellor at Law as part of the Season 41 Sunday Afternoon Film Buffs Series “A”, Programme 2.

Production Company: United Artists. Producer: Stuart Millar, Lawrence Turman. Director: Franklin Schaffner. Screenplay: Gore Vidal, based on his play. Music: Mort Lindsey. Costumes: Dorothy Jeakins. Cinematographer: Haskell Wexler. Assistant Director: Richard Moder.

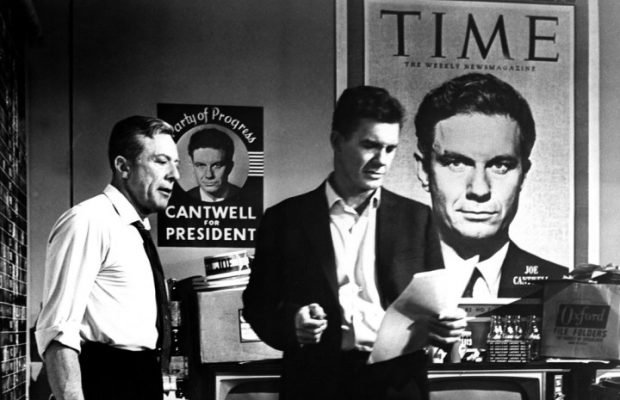

Cast: Henry Fonda (William Russell), Cliff Robertson (Joe Cantwell), Edie Adams (Mabel Cantwell), Margaret Leighton (Alice Russell), Shelley Berman (Sheldon Bascomb), Lee Tracy (Art Hocksader), Ann Sothern (Mrs. Gamadge), Gene Raymond (Don Cantwell), Kevin McCarthy (Dick Jensen), Mahalia Jackson (herself), Howard K. Smith (himself), John Henry Faulk (T.T. Claypoole), Richard Arlen (Oscar Anderson), Penny Singleton (Mrs. Claypoole), George Kirgo (Speechwriter), George Furth (Tom), Anne Newman (Janet).

The Best Man, Gore Vidal’s second play, opened in New York on March 31, 1960, toward the end of the bland Eisenhower era with its aura of invincible smugness. The year 1960 was, of course, a convention and election quadrennial, and for the first time in eight years the ultimate outcome was a betting proposition. In liberal demonology, the McCarthy hard smear had been replaced by the Nixon soft slash. Consequently, The Best Man functioned best when its allegorical archetypes suggested real-life politicians. A Time subscription was not required for the deduction that William Russell, who would rather be pure than President, passed reasonably well for Adlai Stevenson. The fit was even tighter for unscrupulously pragmatic Joseph Cantwell as Dick Nixon. Melvyn Douglas and Frank Lovejoy, two tired character actors, were evenly if uninspiringly matched in Vidal’s convention fireworks, but the play, and later the picture, was dominated by Lee Tracy’s ripsnorting outbursts as Arthur Hockstader, or Truman transcended.

Now, four years and two Presidents later, The Best Man has come to the screen, considerably improved int he process of transition. The original casting imbalance that reduced Douglas and Lovejoy to mere antagonists in the presence of Tracy’s protagonist has been righted somewhat by the substitution of Henry Fonda and Cliff Robertson in the Stevenson-Nixon roles. Fonda and Robertson not only act more subtly than Douglas and Lovejoy, they are richer in those iconographical associations that enable movies to excel in the realm of intermediate excellence. Over the years, Fonda has become entrenched as Hollywood’s populist of the Left, virtually in opposition to James Stewart’s populist of the ruggedly individualistic Right. Against Fonda’s classic awkwardness, Robertson’s compressed grace makes it own comment on the modern politician losing in passion what he gains in poise. In fact, Robertson can serve double duty in 1964 as an approximation of both Dick Nixon and Bobby Kennedy, on record as two of Gore Vidal’s lesser enthusiasms. To round out the analogies, Fonda portrayed young Abe Lincoln more than a quarter of a century ago, and Robertson young Jack Kennedy less than a year ago.

Under Franklin Shaffner’s intelligently graded direction, The Best Man has profited in its adaptation to the screen simply by being exposed to the hot air of Southern California. Even Jo Mielziner’s pointedly vulgar stage suites pale in comparison with the camera’s casual documentation of a Los Angeles hotel bleached by the sun into a dim replica of a dwelling for humans. More important is the sheer sensuousness of power unveiled for its own sake as spectacle. One shot of a frenzied convention may not be worth a thousand words of Vidal’s rhetorical discussion of power and responsibility, but said shot at the very least provides the kind and scope of objective correlative singularly lacking on an austere stage. Finally, te interplay of helicopters, walkie-talkies, and double-entry television screens establishes the cinema’s ascendancy over the theatre as the medium of modernity.

Casting coups and technical flourishes aside, The Best Man remains a writer’s picture–that is, one writer’s picture–and the critical problem is determining whose ox is being gored. Nixon’s? Stevenson’s? The electorate’s? In an article, “Notes on The Best Man” (Theatre Arts, July 1960), Mr. Vidal wrote, “I use the theatre as a place to criticize society, to satirize folly, to question presuppositions.” Allowing for the inherent pomposity of such statements of intention, the author’s tone is a striking blend of condescension and civic-mindedness, a highbrow’s acknowledgement of the mass media, an intellectual diving from his ivory tower of self-expression (the novel) into the mainstream of social responsibility (the dramatized pamphlet).

…For Vidal, however, character is less decisive than image. The author’s unsuccessful congressional campaign in New York’s heavily Republican Second District has undoubtedly contributed to his cynicism about the effect of issues on the body politic. Consequently the modifications of his stage play for the screen do not alter the basic relationships of his characters. Jokes about birth control have been replaced by jokes about civil rights. References to disarmament and recognition of Red China have been dropped outright, and Lee Tracy’s Rabelaisian showstopper–“I personally do not care if Joe Cantwell enjoys deflowering sheep by the light of a full moon”–has been wittily mechanized in tune with the agricultural revolution to “I personally do not care if Joe Cantwell has carnal knowledge of a McCormick reaper.”

Where play and screenplay are perfectly consistent is in the focus on command decisions. “My God,” Hockstader exclaims to Russell, “what would happen if you had to make a quick decision in the White House when maybe all our lives depended on whether you could act fast…and you just sat there, the way you’re doing now, having a high old time with your divided conscience?”

The final Russell-Hockstader exchange on power has the eerie ring of Vidal’s own internal dialogue as a tormented literary-political creature.

Russell: And so, one by one, these compromises, these small corruptions destroy character.

Hockstader: To want power is corruption already. Dear God, you hate yourself for being human.

Russell: No. I only want to be human…and it is not easy. Once this thing starts, there is no end to it, which is why it should never begin. And if I start…Well, Art, how does it end, this sort of thing?

Hockstader: In the grave, son, where the dust is neither good nor bad, but just nothing.

Village Voice, Andrew Sarris, August 20, 1964

Notes by Jaan Salk

Leave a Reply