The Eagle (1925)

Toronto Film Society presented The Eagle (1925) on Monday, April 22, 1968 as part of the Season 20 Monday Evening Silent Film Series, Programme 6.

Toronto Film Society

SILENT SERIES

1967-68

Main Auditorium, UNITARIAN CHURCH, 175 St Clair West

-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-

Programme No. 6

Monday April 22, 1968

8.15 pm

Harold Lloyd in Step Lively: approx 12.00

Snub Pollard in Springtime Saps 10.30

Rudolph Valentino in The Eagle (1925) approx 70.00

—————————————————————–1.32.30

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Step Lively

with Harold Lloyd, Bebe Daniels and “Harold” Pollard.

Made by the Rolin Film Company (Hal Roach).

Copyright by Pathé Exchange, Inc., June 24, 1918.

(But Kalton Lahue lists it as having been released in late December, 1917).

1 reel. (Silent speed)

Springtime Saps

with Snub Pollard and Marvin Loback.

(Date unknown, but obviously latter 1920s)

Reissued byMotion Picture Jubilee Productions with a musical sound track).

1 reel. (Sound speed).

With these two short films, made about ten years apart, we offer further excerpts from the Snub Pollard story. Between 1916 and 1919 Pollard supported Harold Loyd in numerous one- and two-reel comedies (both the Lonesome Luke series and those in which Loyd played the bespectacled young man which, after December 1917, he was to play exclusively),–all produced by Hal Roach; after which Roach made Pollard a star of his own comedies. Kalton C. Lahue, in his book “World of Laughter” (which I should have consulted before writing last month’s notes), gives a complete list of the Snub Pollard shorts down to January, 1927. (He neglects to tell us what happened after that). The list reveals neither a Double Trouble nor a Springtime Saps, so these titles may ver well be the invention of Motion Picture Jubilee Productions, which would explain why we failed to find either of them listed int he Library of Congress catalogue. The two films were obviously (from internal evidence) made around the same time, but Sprintime Saps is presumably a cut-down version (for TV?) of what was originally a two-reeler. All the Pollard films on Lahue’s list were made by Hal Roach except the last five (Sept 1926-Jan 1927), which were produced by Pollard’s own company and released by Weiss Brothers Artclass. (This means, of course, that the credits we printed last month with Double Trouble are–apart from the players–quite wrong. If you file your program notes, please cross those credits out).

Incidently, any of you who may be seeing Harold Lloyd for the first time should be cautioned that this early film is not one of his vintage classics!

* * *

The Eagle

Producer and director: Clarence Brown

Based on the story “Dubrovsky” by Alexander Pushkin

Adaptation and screen play: Hans Kraly

Settings: William Cameron Menzies

Film Editor: Hal C. Kern

Cameraman: George Barnes

Titles: George Marion Jr.

Copyright November 16, 1925, by John W. Considine Jr.

Released byUnited Artists Corp., in 7 reels

Players: Rudolph Valentino, Vilma Banky, Louise Dresser, Albert Conti, Carrie Clark Ward, George Nichols, James Marcus.

Alexander Pushkin (1799-1837) is Russia’s greatest poet; and one wonders what Russian music (opera in particular) would ever have been without him. Boris Godonuv, Russian and Ludmilla, Eugene Onegin, The Queen of Spades, Coq D’or, Navra, The Fountain of Bakhshisarai . . these are only a few of the better known operas and ballets based on poems, plays or novels by Pushkin. (Among the lesser known operas is a Dubrovsky (1895) by Eduard Napravnik, still performed in Russia). But off-hand we can think of no other film (apart from opera films) based on Pushkin–though Russia must have produced many that we don’t know about. Dubrovsky was one of several unfinished manuscripts that were left behind at Pushkin’s early and sudden death (in a duel). It has an ending of sorts, but one cannot imagine that Ppushkin meant to leave it that way, and he may very well have put it aside until he could think up a better one.

One thing is certain: Mr Kraly was very free in his adaptation, for Pushkin’s tale was set in his own lifetime, and the person of Empress Catherine the Great (1762-96) isn’t so much as even hinted at. Why she was dragged into the film we don’t know, unless Kraly (or someone giving him instructions) had been impressed by the 1923 Pola Negri film Forbidden Paradise (in which, however, the character of Catherine of Russia was transferred to a present-day mythical kingdom). At any rate, “based on” is obviously the operative word here.

Pushkin or no, The Eagle gave Rudolph Valentino’s career a much-needed shot in the arm. Outwardly he was still the great matinee idol, the “sheik” of every flapper and her mother; but in truth his drawing power at the box-office had slumped considerably in the three years since he had made Blood and Sand (1922).

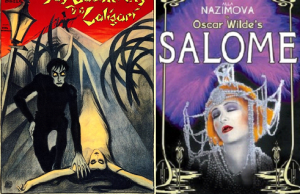

We have told the story twice before, in program notes for our TFS Silent Series showings of Blood and Sand (Nov 8, 1963) and The Son of the Sheik (Dec 6, 1965); but apart from the fact that many of our members this year may not have been with us in those previous seasons, retelling the story can also serve as a continuation of the history of that strange and enigmatic character, Natacha Rambova, whom we’ve already discussed in connection with her designs for Nazimova’s Salome (see notes for Feb 19, 1968). Besides, we have recently read two more accounts of her life of Valentino, differing in many details from each other as well as from our previous source, and some points need to be revised, or at least queried. (But we reserve the right to quote verbatim large chunks of our former notes without acknowledgement).

* * *

Rodolfo Alfonzo Rafaelo Pierre Filibert Guglielmi di Valentina d’Antonguolla was no penniless immigrant when he landed in New York in 1913, two days before Christmas, at the age of 18. (Immigrant, yes; penniless, no). His father had been a well-to-do farmer and veterinarian; his mother was French, the daughter of a Paris surgeon; and the boy, born in Castellaneto, Italy, on May 6, 1895, had graduated from the Royal Agricultural School in Genoa. (He had wanted to enter the Royal Naval Academy but had been rejected because his chest expansion wasn’t great enough–a humiliating blow which stung the boy into intensive calisthenics; small wonder that in later years Valentino was inordinately proud of his excellent physique). Having disgraced his family by a minor escapade in Paris in the summer of 1913, he was shipped off to America with a comfortable sum of money to tide him over until he got a job–presumably in some form of agriculture or gardening. He had no relatives in the New World, but he soon made good friends in New York, and had a very good time there for several months…until his money ran out and he was reduced to sleeping on park benches.

Rodolfo Alfonzo Rafaelo Pierre Filibert Guglielmi di Valentina d’Antonguolla was no penniless immigrant when he landed in New York in 1913, two days before Christmas, at the age of 18. (Immigrant, yes; penniless, no). His father had been a well-to-do farmer and veterinarian; his mother was French, the daughter of a Paris surgeon; and the boy, born in Castellaneto, Italy, on May 6, 1895, had graduated from the Royal Agricultural School in Genoa. (He had wanted to enter the Royal Naval Academy but had been rejected because his chest expansion wasn’t great enough–a humiliating blow which stung the boy into intensive calisthenics; small wonder that in later years Valentino was inordinately proud of his excellent physique). Having disgraced his family by a minor escapade in Paris in the summer of 1913, he was shipped off to America with a comfortable sum of money to tide him over until he got a job–presumably in some form of agriculture or gardening. He had no relatives in the New World, but he soon made good friends in New York, and had a very good time there for several months…until his money ran out and he was reduced to sleeping on park benches.

As it turned out, however, those prodigal months had not been altogether a waste. From his sociable friends he had picked up the latest ballroom dances, including the fashionable tango. (Or so one of our witnesses testifies. Another account claims that he had learned it during his summer in Paris). A born dancer, it came so easily to him that he thought nothing of it; but for the rest of his life his dancing would be something he was to fall back on it time of need, even during the height of his fame as a film star. In 1914 it saved him from starvation: he got a job as a hired dance partner (a gigolo) in Maxim’s restaurant in New York. This led to his becoming the partner of a popular vaudeville dancer, Bonnie Glass, (who needed him to replace her previous partner, Clifton Webb). His dancing tours took him to California, where at a friend’s suggestion he began looking for work in the movie studios.

For three years (1918-20) he made a precarious living in Hollywood, falling back on his dancing whenever film jobs became too scarce. He played everything from extra to leading men; but his unmistakably Latin face mostly led to his being type-cast for villain roles–such being the outlook in the U.S.A. at that time. (The currently popular male stars were the clean-cut American types like Wallace Reid, Charles Ray and Douglas Fairbanks). Not until 1920 did someone realize that his exotic looks could be turned to advantage. The scenario writer June Mathis saw him in a minor role as a villainous dancing master in the Clara Kimball Young film Eyes of Youth, and decided that this was the ideal actor to play the tango-dancing Argentine hero of The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, which she was adapting to the screen for production by Metro. It was perfect casting, for the boy with the too-foreign face was suddenly discovered to be blazing with sex appeal. When the film was released in March, 1921, (to become one of the biggest financial successes of all time) Rudolph Valentino steed from obscurity to popularity.

At the same Metro studios, in the spring of 1921, Alla Nazimova was making preparations for her next film, Camille, with Natacha Rambova designing the sets and costumes, and, as artistic director, having the final word on all matters including casting. When Nazimova saw Valentino, it occurred to her that he would make an ideal Armand, and accordingly she sent him to Rambova for her approval. Rambova looked him over coolly, and okayed the casting. But the meeting had repercussions far beyond the filming of one more Camille. Valentino fell immediately and permanently in love with Natacha Rambova.

Metro, strangely enough, never appreciated what a potential goldmine they had in Rudolph Valentino, and didn’t bother to renew his contract. The Famous Players-Lasky Company (Paramount) was quick to take advantage of this, and his first film for them was another inspired piece of casting: the title role of The Sheik in the screen adaptation of the popular novel by E.M. Hull. Released in November 1921, this is the film that really made Valentino. The novel is what is known as “trash”: the wish-dream of a frustrated spinster novelist, but its not-yet-hackneyed tale of a white Sheik of the desert who kidnaps and tames a haughty English girl struck a responsive chord i thousands of female hearts; and its embodiment on the screen by this handsome foreign youth, whose exotic personality blended sleekness and savagery, had an intoxicating impact on the women of that time, puritanically brought up to resist advances but subconsciously hoping to be raped. In real life Valentino was no such thing; he was just a nice, likeable, shy young Italian boy. But he was a good actor, and he could assume the personality of a passionate Sheik as successfully as he had impersonated the crooks and villains of his earlier films. American women, starved for romance by their prosaic husbands and boy friends, found in Valentino the dream lover whose attitude toward women was an excitingly delicate balance between worshipful respect and ruthless seduction. Their prosaic husbands and boy friends, of course, snorted in derision; but they quickly began wearing their hair in a slick-back “pompadour” like Valentino’s; and “sheik” throughout the rest of the 1920s was the slang word for any fashionable, up-to-the-minute, sophisticated young man, attractive to the young flappers and “shebas”.

Valentino the dream lover would have swept the beautiful Natacha Rambova off her feet. The real life Rudy patiently courted her and gradually thawed her cool indifference. It is doubtful if she ever really loved him; but few people can resist the flattery of adoration, and they soon became an inseparable couple. Natacha was a woman with a great cultural background, and tastes that were firmly set. Rudy had none of his background, but he had an open mind and was eager to learn; and because he worshiped her, he dutifully absorbed the things she taught him–about books, paintings, tapestries, antiques. (She also converted him to her belief in spiritualism). Perhaps she raised his standards of Art a little too high; he might have gotten along with his studio a little better if he hadn’t been so insistent on high artistic standards. (He would never have made The Sheik if Natacha had had any say in the matter). At any rate, Natacha must have enjoyed influencing his eager young mind.

Only one thing prevented their marriage: Valentino was still legally the husband of the girl he had been briefly married to in 1919. They had separated almost at once, but no divorce action had been taken. She was now persuaded to take this step, and on March 9, 1922, she was granted an interlocutory degree of divorce: one whole year must go by before either of them could marry again. To Valentino it seemed too long; and when someone assured him that one could get married in Mexico without having to wait, he and Natacha slipped across the border into Tia Juana, on May 13, 1922, just after he’d completed Blood and Sand, and were married by a Mexican justice of the peace. But they were wrong. The moment they crossed the border back into California, Valentino was arrested and thrust into the county jail in Los Angeles on a charge of bigamy, with bail set at $10,000. Fortunately they were able to convince the judge that the marriage had not been consummated, but they were ordered to live apart until they could be married legally.

Paramount was naturally alarmed lest all this unsavory publicity ruin Valentino at the box-office. But Blood and Sand was released (Sept 1922) and proved both a money-maker and a critical success–and it was probably the best film he ever made. Indeed, though no one knew it, with Blood and Sand Valentino was at the crest of his career. The rest was a downward curve . . until The Eagle reversed this trend, The Son of the Sheik topped it, and his death sealed it off.

Blood and Sand was followed by a clinker called The Young Rajah (Nov 1922), and Valentino, unhappy about the film and unhappy in his personal life, became increasingly irritable, and finally insisted on having both a raise in salary and full approval of every script. When the studio refused, he walked out. And as he was still under legal contract, Famous Players slapped an injunction on him that prevented him from making films for anyone else until after February 1, 1924.

Valentino was paying dearly for the artistic idealism that Natacha had instilled into him. He was penniless, unemployed, and $48,000 in debt to his lawyers. But once again his talent for dancing came to his rescue–coupled with that of Natacha, a former ballet dancer. They toured the country in vaudeville as dancing partners, sponsored by a beauty cream manufacturer, and played to packed houses. (and this might be the place to point out that, apart from a beauty contest gimmick and Valentino’s sales pitch for the face cream, their act consisted of dancing only. In short, Valentino never sang. That recording of him singing the Kashmiri Song, which Max Ferguson periodically plays on his radio program–usually accompanied by nide comments–was a private recording which, unfortunately, was released commercially after his death by someone hoping to cash in on his posthumous popularity).

Valentino was off the screen for nearly two years (not counting the reissues of many of his pre-1921 pictures by film companies eagerly digging out the forgotten treasures buried in their vaults), but the success of his vaudeville tour convinced Hollywood that he was still a valuable property. He finally signed two film contracts: one with an independent producer named J.D. Williams, to take effect as soon as he was legally free from Paramount; the other, settling his differences with Paramount, for whom he agreed to make two more films.

His first film for Paramount was Monsieur Beaucaire (released August 1924), for which Natacha Rambova (now legally Mrs Valentino) designed the costumes. Even Jesse Lasky concedes that her costumes were very beautiful; but it’s the only good thing he can say for her. With her husband’s loving approval she insisted on supervising every detail of his films, arguing with everyone from the director down to the lowliest grip, and generally getting into everyone’s hair. Monsieur Beaucaire generally received good reviews, A Sainted Devil (Nov 1924) did not; but box-office returns indicated that Valentino’s popularity had slipped noticeably, and these weren’t the films to lure his public back. The Valentinos left at the end of his contract, and the Paramount studios heaved a sigh of relief.

Natacha looked forward to the new company, where she’d be free to run things exactly as she wished. She wrote a story about Moorish Spain called The Hooded Falcon. They got June Mathis to write the script, and Rudy and Natacha went off to Spain and had a wonderful time buying all sorts of authentic properties to be used in the film. A fortune was lavished on The Hooded Falcon before the script was even written; and J.D. Williams, who was nearly going out of his mind, finally persuaded them to put off the extravagant Hooded Falcon until after they’d done another film whose script was ready: Cobra, based on a Broadway play that had starred Judith Anderson. By the time this was finished, Williams threw up his hands in despair and frankly broke his contract. Once again Valentino was out of a job and deeply in debt.

United Artists then offered Valentino a very good contract, but made one firm stipulation: Mrs Valentino was to keep strictly out of it. Desperate, Valentino signed it. Natacha, as can be expected, was deeply hurt. But Valentino softened the blow by agreeing to finance a film which she was to produce by herself, exactly as she wanted it. Here at last was Natacha’s big opportunity, which she had been wanting ever since Nazimova’s company had folded. Her story was about the cosmetics business and was called What Price Beauty? Nita Naldi was the star, and the cast included one young actress making what seems to have been her first screen appearance: Myrna Loy. But What Price Beauty? was a complete and utter failure. It didn’t even leave a legend behind it; it just sank. Was it indeed a bad film? Is it true that Rambova had more ambition than talent, except as a designer? Or was it a film too far in advance of its time? If we could see it today, would we discover it to be a masterpiece? or even a flawed masterpiece? Natacha made so many enemies in Hollywood that there were few if any who would give her the benefit of the doubt. And we today will never know, for it’s highly improbable that there’s a single print of What Price Beauty? left in existence.

At any rate, after its failure Natacha gave up all pretense of being interested in Rudolph Valentino. She moved to New York, where her next film venture was in front of the camera–a leading role in a film that was notable only for its ironically apt title: When Love Grows Cold. After that she moved to Paris, and a divorce soon followed.

In the meantime, things were prospering for Valentino at last. Now under proper management, his career took a turn for the better. His first film for United Artists was The Eagle, and it quickly began rounding up the fans who had loved him once but had become more discriminating. Here was the old Rudy back at last. His second film for U.A., The Son of the Sheik (July 1926), was an obvious attempt to capitalize on the popularity of his most famous role; but it actually worked. Indeed, for once a sequel was better than the original. Valentino’s four years of troubles were over at last.

Following the Los Angeles premiere in July, Valentino went east to make personal appearances with the New York opening in August. Everywhere he went the fans mobbed him.

For several months Valentino had been plagued with mysterious sharp pains in his stomach; but with his native distrust of doctors he ignored these symptoms, suffering in silence till they went away. Suddenly, on August 15, he collapsed and was rushed to the hospital where he was operated on for appendicitis and gastric ulcers; but it was already too late. He died of peritonitis on August 23, 1926, at the age of 31.

With perfect timing, Valentino died at the beginning of an upswing of renewed popularity, thereby ensuring its permanence. His five year career as a screen idol, in spite of its birlliant moments, is a sad record of fumbled opportunities and tragic mismanagement, but he bought atonement for this with his life. Natacha Rambova inevitably emerges as the villainess of the story, the woman for whom he ruined himself,–but like many a villain of fiction, a very fascinating a colorful character that one would like to know more about.

* * *

VILMA BANKY was also Valentino’s leading lady in The Son of the Sheik, but she is best remembered by surviving moviegoers of that era for the series of films in which she co-starred with Ronald Colman, including the first version of The Dark Angel which later became a very successful vehicle for Bette Davis. She was born in Budapest in 1903 and began her movie career in Vienna. She was brought to Hollywood in 1925 by Samuel Goldwyn. She later married Rod La Roque, and retired from films in 1930.

LOUISE DRESSER was a prominent character actress in films at that time. Another important role she played that year was in a film called The Goose Woman. At the moment of writing htese lines we are unable to lay hands on any reference book that can confirm our recollection that she was related (sister?) to Paul Dresser, the turn-of-the-century composer of popular songs (MY GAL SAL, et al). Paul Dresser was a brother of the novelist Theodore Dreiser; but his connection with Louise Dresser is something we’re less certain about . . except that we’re sure there is a connection.

* * *

APPENDIX: Louise Brooks called attention to some errors in the notes on The White Hell of Pitz Palu last month. That film did not “immediately” precede Die Dreigroschenoper, L’Atlantide and Kamaradschaft, as was carelessly stated; there were a few others in between. (A complete filmography for G.W. Pabst can be found in the February 1964 issue of FILMS IN REVIEW). We might add that White Hell, though made prior to Diary of a Lost Girl, was not released till after it. Miss Brooks also points out that Gustav Diessel died, not in the “early 1950’s” but on March 20, 1948, in Vienna, at the age of 48.

Program-note writers who, like myself, have to take their material like jackdaws from the writings of others whom they trustfully assume to have done the research that we have neither time nor facilities for, are often dismayed to discover these “authorities” blandly contradicting one another. Here is just one example: Adela Rogers St Johns, in an article on “Valentino, the Life Story of ‘the Sheik'”, which first appeared on September 1929, says “The definite break with Paramount came on October 1, 1922“. Brad Steiger and Chaw Mank, in their paperback VALENTINO (1966), say “….Rudy looked upon their action as a breach of contract. He would, he announced on August 30, 1922, look for a better deal elsewhere”. (They go on to give the actual date of the injunction as September 14, and the affirmation of this, by the Appellate Division in New York, as December 8). Who is right? Which one (if either) checked the dates carefully, and which one seemingly made something up? As Louise Brooks says: “Both of us could be wrong–only one of us could be right”. And what is a poor jackdaw, writing his notes in his spare time at night, with a deadline coming up, to do when he runs into these conflicting statistics? What is he to do if he wants to “tell it like it was”, but is in no position to know when his authorities are reliable? (As long as you know you don’t know, you’re fairly safe. But what if I’d read only one of those two accounts?)

And with that caveat on everything in the foregoing pages, we end the 1967-68 season of the Toronto Film Society’s Silent Film Series. Shall we all be together again in the fall?

Notes by Fraser Macdonald

April 9, 1968

Leave a Reply