The Invisible Man (1933)

Toronto Film Society presented The Invisible Man (1933) on Monday, November 11, 1985 in a double bill with The Seventh Cross as part of the Season 38 Monday Evening Film Buffs Series “B”, Programme 3.

Production Company: Universal. Directed by: James Whale. Screenplay: Philip Wylie and R.C. Sheriff, from H.G. Wells’ novel and The Murderer Invisible by Wylie. Photography: Arthur Edeson, John Mescall. Special Effects: John P. Fulton. Makeup: Jack Pierce.

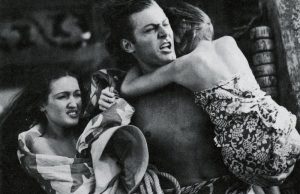

Cast: Claude Rains (Jack Griffin), Gloria Stuart (Flora Cranley), William Harrigan (Doctor Kemp), Henry Travers (Doctor Cranley), Una O’Connor (Jenny Hall), Forrester Harvey (Herbert Hall), Holmes Herbert (Chief of Police), E.E. Clive (Jaffers), Dudley Digges (Chief of Detectives), Harry Stubbs (Inspector Bird), Donald Stuart (Inspector Lane), Merle Tottenham (Milly), Walter Brennan (Man With Bike), Dwight Frye (Reporter), Jameson Thomas (Doctor), John Carradine (Informer), John Merivale (Boy).

All of us must have, at least once, fantasized about being invisible, and in The Invisible Man, H.G. Wells explores the possibilities and consequences on an ill-fated scientist who discovers the secret of invisibility, applies it to himself, but, alas, fails to develop a restorative. “There must be a way back!” he cries to himself. “God knows, there’s a way back!”

“I meddled in things that man must leave alone,” the scientist, Griffin, (Claude Rains), confesses during the dying moments of the movie. But before those moments occur we are treated to 70 minutes of fascinating film that expertly combine science fiction and horror with humour. The film suceeds in presenting an aura of mystery from the initial entrance of the Invisible Man, his head covered with bandages and dark glasses over his eyes, to the scene where the police force him out into the snow, (his footprints can be seen, you see), by setting ablaze the barn in which he has taken shelter.

Boris Karloff turned down the title role, balking at the requirement that his face be swathed in bandages and entirely unseen until the last moments of the film. This led the way for Claude Rains’ Hollywood debut, and he ran away with the part, creating a malevolent presence with his expressive British voice (which someone once described as sounding “like honey with some gravel in it”) and arch delivery of the incisive, elegant dialogue. Rains reveled in such melodramatic speeches as “We’ll begin with a Reign of Terror. A few murders, here and there. Murders of great men, murders of little men, just to show we make no distinction. We might even wreck a train or two. Just these fingers, ’round a signalman’s throat.”

James Whale directs the film with that mordant wit which also made The Old Dark House and Bride of Frankenstein classics of their genre, and he receives valiant support, not only from Rains, but from Philip Wylie and R.C. Sheriff who combined to write the intelligent script, and John P. Fulton who created the artful visual effects, borrowing techniques from stage magicians. The unsettling experience of watching Rains remove his glasses, bandages and clothing to reveal absolutely nothing underneath was accomplished by dressing a stunt man in a black velvet body suit, complete with gloves and mask. Over this he wore the Invisible Man’s clothing and disrobed in front of a matching black velvet background. When the mortally wounded megalomaniac loses his invisibility, Fulton produced another chilling bit of trickery. First, we see a depression in the pillow of the death bed and a carpet draped over an unseen form. Gradually, his bones appear, fleshed out by muscles, nerves and finally, skin. This sequence was done in the camera without matte work involved. The pillow and sheet were made of plaster and papier-mache, and the rest was Fulton’s sophisticated reverse motion of Georges Melies’ old illusion: in a series of stop-motion shots, a skeleton was dissolved into a more complete dummy and so on, ending with actor Rains.

Apparently a French film entitled The Invisible Man was made as early as 1910. But this picture is most likely just a retitling of “Les Invisible” (seen in the United States as Invisible Thief), directed by Gaston Velle and Gabriel Moreau in 1905 for the French company Pathe and released in 1910. It was not until 1931 that an authorized version of The Invisible Man was announced for filming by Universal. As Donald Glut writes in Classic Movie Monsters: “Universal had already purchased a novel similar to The Invisible Man, the Philip Wylie story The Murderer Invisible (1931). It was the studio’s intention to merge the two stories into one and they brought in a number of staff writers to perform this task. By the time Sherriff was given the assignment of writing The Invisible Man, Universal had already amassed a stack of rejected scripts, from which he was supposed to extract the best elements and create the final screenplay. When Sherriff asked for a copy of the original Wells novel upon which to base his screenplay, he was informed that none existed on the lot and that he was to base his version on the other adaptations on file at Universal. Finally, Sherriff was able to locate a copy of the novel at a market in Chinatown and purchased it for 15 cents.

Like Dracula, Frankenstein and The Mummy, The Invisible Man inspired a number of sequels–principally, The Invisible Man Returns (1939) with Vincent Price and Sir Cedric Hardwick, directed by Joe May (with script by May and Curt Siodmak); Invisible Agent (1942) with Jon Hall, Sir Cedric Hardwicke and Peter Lorre, directed by Edwin L. Marin, andThe Invisible Man’s Revenge (1944) with Jon Hall, Gale Sondergaard and John Carradine, directed by Phil Forde, with a screenplay by Bertram Millhauser. The Invisible Woman (1940) with Virginia Bruce and John Barrymore was not really a sequel but an outright comedy directed by A. Edward Sutherland, with a script by Siodmak and May. We won’t even mention Abbott and Costello Meet the Invisible Man (1951) or the countless inferior versions that have turned up on television.

Notes by Harry Purvis

Leave a Reply