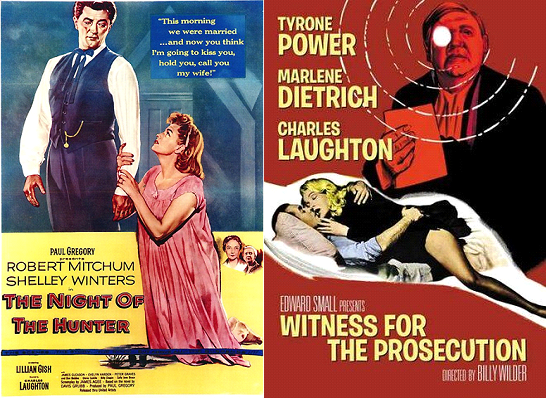

The Night of the Hunter (1955) and Witness For the Prosecution (1957)

Toronto Film Society presented The Night of the Hunter (1955) on Monday, April 30, 1984 in a double bill with Witness For the Prosecution (1957) as part of the Season 36 Monday Evening Film Buffs Series “B”, Programme 10.

The Night of the Hunter (1955)

Production Company: Paul Gregory Productions, Distributed through United Artists. Director: Charles Laughton. Screenplay: James Agee and Charles Laughton, from the novel by Davis Grubb. Photography: Stanley Cortez. Music: Walter Schumann. Editor: Robert Golden and Charles Laughton. Art Director: Hilyard Brown. Sound: Stanford Naughton.

Cast: Robert Mitchum (Preacher Harry Powell), Shelley Winters (Willa Harper), Lillian Gish (Rachel), Evelyn Varden (Icey), Peter Graves (Ben Harper), Bill Chapin (John Harper), Sally Jane Bruce (Pearl Harper), James Gleason (Uncle Birdie), Don Beddoe (Walt), Gloria Castillo (Ruby), Mary Ellen Clemons (Clary), Cheryl Callaway (Mary).

Witness For the Prosecution (1957)

Production Company: Theme Pictures, an Edward Small Presentation. Producer: Arthur Hornblow, Jr. Director: Billy Wilder. Assistant Director: Emmett Emerson. Screenplay: Billy Wilder, Harry Kurnitz, based on the short story and play by Agatha Christie. Adaptation: Larry Marcus. Director of Photography: Russell Harlan. Editor: Daniel Mandell. Art Director: Alexander Trauner. Set Decorator: Howard Bristol. Music: Matty Malneck. Musical Director: Ernest Gold. Orchestration: Leonid Raab. Song: “I Never Go There Any More,” by Ralp Arthur Roberts and Jack Brooks. Sound: Fred Lau.

Cast: Tyrone Power (Leonard Vole), Marlene Dietrich (Christine Vole), Charles Laughton (Sir Wilfrid Robarts), Elsa Lanchester (Miss Plimsoll), John Williams (Brogan-Moore), Henry Daniell (Mayhew), Ian Wolfe (Carter), Una O’Connor (Janet McKenzie), Torin Thatcher (Mr. Meyers), Francis Compton (Judge), Norma Varden (Mrs. French), Philip Tonge (Inspector Hearne), Ruta Lee (Diana), Molly Roden (Miss McHugh), Ottola Newsmith (Miss Johnson), Marjorie Eaton (Miss O’Brien).

Charles Laughton (1899-1962) was one of the most esteemed of film actors for the first thirty years of sound, an done of the most versatile. After stage experience in England, and a handful of British films, he played in his first year in Hollywood (1932) an overblown, even campy role in James Whale’s The Old Dark House, a downtrodden clerk in Lubitsch’s portion of If I Had a Million, and the Emperor Nero in DeMille’s The Sign of the Cross. These would be the main lines of his career: frequently overripe performances (even in his very last film, Advise and Consent), frequently heroic cowards or little men finally triumphant (This Land is Mine, Tales of Manhattan), frequently larger than life historical figures (The Private Life of Henry the Eighth). But his truly unforgettable roles, while related to these three basic categories, cannot so easily be pigeon-holed. Who could forget him standing legs wide apart on the quarter-deck, as Captain Blight? Or reciting the Gettysburg Address in Ruggles of Red Gap? Or his electoral malignity in The Barretts of Wimpole Street, or his spectral whimsicality with Margaret O’Brien in The Canterville Ghost? His small-time villainy in The Bribe, or his big-time villainy in The Big Clock? Or, perhaps above all, his underplayed imperiality (unlike his own Neros and Gracch uses) in Von Sternberg’s tantalizingly unfinished I, Claudius? This great, and often subtle actor, who only less often overplayed, was the subject of a TFS retrospective–the first ever devoted to a single actor–in early 1968, and our writer summed him up then: “Even his greatest admirers would admit that he occasionally indulged in excess, but even on these occasions it is the excess of gusto and dynamism of a man who truly loved acting. At his best, he has created finely-wrought, utterly believable characterizatons that have lived in the memories of moviegoers for generations.”

TFS has also shown The Night of the Hunter before, on March 5, 1973. Though this was the only film he ever made as director, and it failed at the box-office, it was by no means his only attempt at directing actors. He had taken a large part in directing what is still a landmark in the landmarks of the postwar theatre, Brecht’s Galileo, in which he also played the lead, in 1947, had had notable successes in dramatic readings of John Brown’s Body and the famous “Don Juan in Hell” sequence in Man and Superman, and was sole director, the year before The Night of the Hunter, of The Caine Mutiny Court Martial, much acclaimed on Broadway. And in Burgess Meredith’s film The Man on the Eiffel Tower (1949), he both played Inspector Maigret and directed the scenes in which Meredith himself acted.

Such is the directorial background, then, that Laughton brought to The Night of the Hunter. And its quality may be prejudged through Lillian Gish’s story that before making it he spent a great deal of time at the Museum of Modern Art running and rerunning the films of D.W. Griffith. And there perhaps is the key to understanding this film–by seeing it as an attempt to transpose certain qualities of the silent cinema, lost for twenty-five years, to the sound film. As Ron Anger said in his notes for the 1973 presentation: “Surely the introduction of sound should not necessarily and in itself have amputated that wonderful ability to see things with the eye of a poet? That ability to tell volumes with a single shot? Many key scenes in The Night of the Hunter are either completely without dialogue or use words as incidental sounds, not to tell the story…. The use of the ‘iris’ effect and the use of extreme long-shots in this movie are direct bows to Griffith, but the whole style of the movie reminds us of the silent era generally.” If the use of animals to define the children and our feelings towards them are pure Griffith, the expressionistic photography calls to mind the silent film in its last years of near-perfection.

Yet though the personal, even eccentric, quality of the vision makes this film distinctly Laughton’s, it is also, to varying degrees, Davis Grubb’s, James Agee’s, Stanley Cortez’s, Lillian Gish’s, and Robert Mitchum’s. Grubb’s novel is a terrifying one, an inverted Tom Sawyer, seen partly through the eyes of the children (named Harper, perhaps to recall Tom’s friend Joe), and involving a treasure and a stalking murderer much more threatening than Injun Joe: it is an adult’s dark childhood fantasy rather than a child’s… As Laughton himself said: “It’s really a nightmarish sort of Mother Goose tale we are telling.” Out of the novel James Agee fashioned a taut script, probably superior to his other fine works (the unrealized Blue Hotel, after Stephen Crane, or The African Queen); he did not live to see the finished film. And Stanley Cortez, who had photographed The Magnificent Ambersons, carried Agee’s script into superb realization, brilliantly capturing the sense of the terror that walks by day as well as by night, and balancing light against dark, frame by frame.

And perhaps only moralists would insist that Lillian Gish’s performance (as LOVE) is superior to Robert Mitchum’s (as HATE). The Night of the Hunter contains, arguably, the best sound performances from these two players: Gish exporing the vein of true grit which always underlay her most vulnerable roles, from Way Down East and Orphans of the Storm to, especially, The Scarlet Letter and The Wind; and Mitchum exploring the kind of seedy menace he had conveyed so well in such diverse films as Out of the Past, Angel Face, and, later, Cape Fear, and combining it with the dogged will to survive which is also very much a part of his screen personality, and so evident in such films as The Red Pony, The Track of the Cat, and his later incarnation as Philip Marlowe.

To turn to Witness for the Prosecution, which contains Laughton’s fourth-last screen performance, is to turn to a world where the menace is more domesticated, but ultimately threatens the stability of the legal system itself. Billy Wilder took Agatha Christie’s highly successful stage play (her own favourite) and made of it a fairly set-bound film. Which suggests that this is less of a Wilder film than most of his are, being restrained by both the play and the dominance of Laughton, whose presence dictated one major change in the play, where Sir Wilfrid is not an invalid, and therefore is not in the toils of his insistent nurse. There are, however, Wilder touches–the characteristic flashback to the wartime meeting of Leonard and Christine, which puts us in possession of essential clues to the characters of the two, and predicts the double denouement. And the running banter between Sir Wilfrid and Miss Plimsoll goes far beyond the piquancy of playing upon the real-life marriage of the two actors, to suggest that major theme: as Sir Wilfrid rides up and downstairs in his mobile chair, both chafing under and evading the nurse’s importunities, we have the theme of the man seemingly in control, actually manipulated by the woman, but with more than one transfer of power, which is seen more seriously in Leonard and Mrs. French, Leonard and Christine, Christine and Sir Wilfrid himself.

The theme of disguises, an obsessive one in Wilder’s work from The Major and the Minor on, and about to come to comic climax in his very next film, Some Like It Hot, is also present here, and may have been one of the featurs of the play that attracted him–though it is difficult to see, under the camera’s relentless eye, how an audience can be fooled by the masquerade upon which the plot turns. (Look at the hands, which Wilder regards as so important in Fedora). And so many of Wilder’s films end, affirming his comic or mordant vision, with a journey begun–even if Walter Neff does not walk down the corridor to the gas chamber (as he originally did) but merely dies in it of gunshot wounds, Norma Desmond makes her journey down the staircase, Sabrina and Linus make theirs on the Ile de France to happiness, and Macnamara his back to the States and an uncertain future. But Witness for the Prosecution ends with a cancelled journey, as Sir Wilfrid foregoes his holiday in Bermuda to take up a new client’s defence (this ending is altered from the play). But the Wilderian questions remain. Can his health survive another trial? Are his new clients manipulations finally at an end? (The plot is already so incredible, perhaps she set up her final action as well?)

For Wilder, according to one of his biographers, Laughton had “the greatest technical range and power of any actor, man or woman, whom he (Wilder) has known.” He wanted him again for the part of Moustache in Irma La Douce, but he was already on his deathbed. Sir Wilfrid was his last great role (we can forgive him the moncle). Nominated for an Oscar, he lost, like just about everything else in that year of elephantiasis, to The Bridge on the River Kwai. He abides and he endures.

Notes by Barrie Hayne

Leave a Reply