The Scarlet Claw (1944) and The Hound of the Baskervilles (1939)

By Toronto Film Society on July 11, 2025

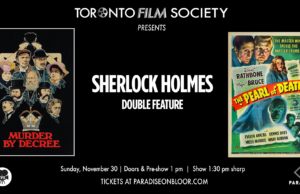

Toronto Film Society presented The Scarlet Claw (1944) on Sunday, July 13, 2025 in a double bill with The Hound of the Baskervilles (1939) as part of the Season 77 Series, Programme 9.

THE SCARLET CLAW (1944)

Production Company: Universal Pictures. Produced by: Roy William Neill. Directed by: Roy William Neill. Screenplay by: Paul Gangelin, based on characters by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Cinematography: George Robinson. Editing: Paul Landres. Music: Paul Sawtell. Released May 26, 1944. Running time: 74 minutes.

Cast: Basil Rathbone (Sherlock Holmes), Nigel Bruce (Dr. Watson), Gerald Hamer (Potts), Paul Cavanagh (Lord Penrose), Arthur Hohl (Emile Journet), Miles Mander (Judge Brisson), Kay Harding (Marie Journet).

The Secret Claw is the 8th of 14 films in the Sherlock Holmes series released between 1939 and 1946, starring Basil Rathbone as Detective Holmes and Nigel Bruce as Dr. John Watson. Thanks to adept direction, set design, photography quality, and the standard of acting exceeding that of a typical “B movie”, the film is now considered by critics and fans alike to be the best of the 12 in the series made by Universal Pictures, though it did not receive wide acclaim at the time of its release.

Although it borrows stylistic elements from other Arthur Conan Doyle works, particularly the eerie atmosphere and suspected supernatural killer from The Hound of the Baskervilles, it is not an adaptation of an actual Sherlock Holmes story. The film’s original title was Sherlock Holmes in Canada as it is set in the province of Quebec (though filmed entirely at Universal Studios in California). The action begins when Holmes and Watson learn about the death of Lady Penrose in the nearby village of La Morte Rouge while attending a Royal Canadian Occult Society conference in Quebec City. Based on a historical legend, the villagers suspect a mythical marsh monster is responsible for her death. Holmes, however, who had a telegram from Lady Penrose before she was killed in which she expressed fear for her life, suspects the culprit to be a human being blending in with the locals.

More grisly murders ensue with the victims connected by a shared secret past and killed one by one by a masked villain. This central plot, coupled with the sinister ambience, Paul Sawtell’s eerie score, and a more intense and less whimsical Holmes than we are used to seeing on screen, make The Scarlet Claw a serial killer horror-mystery before they were ubiquitous. Various camera angles, directive choices, and a mystery that keeps you guessing until the end also bring to mind many of Hitchcock’s works.

The film ends with Holmes and Watson driving to the coast, from where they will sail to England. Holmes closes the film with a flattering speech about Canada, despite the brutality he has just witnessed, which he credits to Winston Churchill: “Canada – lynchpin of the English speaking world, whose relations of friendly intimacy with the United States on the one hand and her unswerving fidelity to the British Commonwealth and the motherland on the other. Canada—the link which joins together these great branches of the human family.”

Ultimately, Rathbone grew tired of playing the famous fictional detective, likening his performances to duplicate prints made from the original film’s portrayal, and the series drew to a close. Despite his personal frustration, the films have continued to entertain viewers for decades, with the Universal entries in the series, including The Secret Claw, undergoing restoration funded by UCLA, Hugh Hefner, and later, Warner Bros from 1993-2001.

Notes by Kathleen McLarty

THE HOUND OF THE BASKERVILLES (1939)

Production Company: 20th Century Fox. Produced by: Gene Markey, Darryl F. Zanuck. Directed by: Sidney Lanfield. Screenplay by: Ernest Pascal, based on The Hound of the Baskervilles, the 1902 novel by Arthur Conan Doyle. Cinematography: Peverell Marley. Editing: Robert Simpson. Music by: David Buttolph, Charles Maxwell, Cyril J. Mockridge, David Raksin. Release date: March 31, 1939. Running time: 80 minutes.

Richard Greene (Sir Henry Baskerville), Basil Rathbone (Sherlock Holmes), Wendy Barrie (Beryl Stapleton), Nigel Bruce (Dr. Watson), Lionel Atwill (James Mortimer M.D.), John Carradine (Barryman), Barlow Borland (Frankland), Beryl Mercer (Mrs. Jennifer Mortimer).

There are few, if any, characters that have endured in terms of both longevity and popularity like the great detective, Sherlock Holmes. Since his first appearance in 1887’s A Study in Scarlet, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s bohemian sleuth has enraptured readers for generations. But despite his brilliance in terms of crime solving, one could argue that Holmes’ most impressive feat is his ability to successfully jump into different mediums. Through comic strips, video games, and even an animated television series in which he is cryogenically frozen and awoken in the far-flung future, Sherlock Holmes has truly appeared in it all. But out of all these non-literary mediums, film has proven itself to be the most enduring. Since his first movie appearance in 1900’s aptly titled Sherlock Holmes Baffled (a comedic take which ran for less than a minute), the character has had hundreds of on-screen adventures in films made around the world, introducing the character to new audiences and further cementing him in the halls of popular culture. Out of these film adaptations, the most important could very well be The Hound of the Baskervilles from 1939.

Directed by Sidney Lanfield and starring the incomparable duo of Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce as Sherlock Holmes and John Watson, The Hound of the Baskervilles is based on the third Holmes novel to come from the mind of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. The film follows Holmes and Watson as they take on a case from one James Mortimer (Lionel Atwill), a friend of Sir Charles Baskerville, head of the Baskerville family. After Sir Charles is found dead near some strange footprints, Mortimer recalls an old legend that the Baskerville family would be hunted by a demonic hound. As fantastical sounding as that may be, it is now up to Holmes and Watson to get to the bottom of this mysterious death as Sir Henry Baskerville, the final heir to the Baskerville estate (Richard Greene), is set to arrive at the secluded family home and possibly walk into a trap.

As the story is a whodunnit at its core, the film hosts an ensemble cast in order to provide plausible culprits within the narrative. With the likes of John Carradine, Wendy Barrie, and a cavalcade of character actors of the time, the characters they portray aren’t necessarily the most three-dimensional characters in film history. However, they fit the needs of the narrative. The story, as all Holmes’s adventures do, requires a cast with specific backstories and motivations that make them probable perpetrators of the crime at hand. But every character feels slightly elevated in a sense, perhaps by the story or perhaps by the direction. Even small characters in this adaptation are memorable and distinct through their dialogue and idiosyncrasies, even if they only exist to be red herrings or to bounce dialogue off of the two leads.

The portrayal of Sherlock Holmes by veteran actor Basil Rathbone has gone down as one of the most popular incarnations of the character and it is easy to ascertain why that is the case. Rathbone plays the bohemian Holmes with an air of grandiosity that audiences had not seen before or perhaps even since. His command of a scene is second to none and he delivers his dialogue with a blunt but intelligent cadence. Even during stretches of the film where Holmes is not present, his aura permeates through his absence. This extends to even the bare essentials of Rathbone’s take on the character. In modern adaptations of the great sleuth, there is a tendency to make Holmes standoffish and rude. In short, modern filmmakers make him an arrogant know-it-all. And while productions such as the BBC Sherlock series and the big-budget Hollywood films from director Guy Richie may be better known to a modern audience, it is Basil Rathbone’s portrayal that is by far the most influential. His Holmes is stoic and cool; almost as if he knows the outcome of the case well beforehand. He is a Holmes whose intelligence doesn’t come at the expense of his personality. Is it any wonder why this version of the character endured for so many entries?

Similarly, Nigel Bruce as the faithful John Watson gets a lot of play in the story, especially in the second act. Many over the decades have chastised Watson as a character who only exists to ask questions and thus enhance the intelligence of our hero. To that end, more recent adaptations see fit to have the two bicker and quarrel like an old married couple. However, The Hound of the Baskervilles, allows Watson to have his own agency beyond the typical dynamic. Bruce plays him as loyal to Holmes but with his own set of skills that is not only recognized by the audience but by Holmes as well. Even if Watson doesn’t have the answers, he has the puzzle pieces that build to those answers. To that end, Nigel Bruce plays the character with warmth and a brotherly quality that gels so very well with Basil Rathbone.

Beyond this film, Rathbone and Bruce became the definitive incarnations of Holmes and Watson of their era, doing one more feature with 20th Century Fox before transitioning to making over a dozen adventures with Universal throughout the 1940s. As both the actors aged, their takes on the characters became more and more solid and would become the defining incarnations for years to come.

A fascinating fun fact is that The Hound of the Baskervilles is one of the first, if not the first, Sherlock Holmes film to take place in the character’s native Victorian Era. Adaptations of the time had a proclivity to advance the timeline so to speak and set the stories contemporaneously (even the later Rathbone and Bruce films are guilty of this; The Pearl of Death (1944) has the two as near victims in a drive-by shooting). However, The Hound of the Baskervilles stands out from the crowd in this way. Trading in automobiles and electricity for carriages and gas-powered lamps may seem superficial for a story that largely takes place in a secluded country estate, but that is far from true. The atmosphere and inclinations of the Victorian period find themselves at home in the story, with the gothic manor and foggy moors creating a fantastic setting for the story. It also adds some narrative sense to the tale, as it is slightly more believable that a family in the 1800s would believe that they were being hunted by a demonic dog.

Even eight decades after its release, The Hound of the Baskervilles remains one of the most popular adaptations of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s work. With its story, atmosphere and legendary portrayals of Sherlock Holmes and Watson, it’s clear to see why it has enjoyed the praise of so many generations of filmgoers. Long may this legendary status continue.

But while watching the film, don’t forget to lock your doors. Because the Hound may be out there…

Notes by Ryan Tocheri

You may also like...

-

News

Thank You from TFS!

Toronto Film Society | July 21, 2025Our matinée on Sunday, August 17th – at the blessedly air conditioned Paradise Theatre – will conclude the Toronto Film Society’s 77th season! But take heart, as we’ll be...

Programming

Sunday Afternoons at the Paradise

Toronto Film Society | January 25, 2026Join TFS for Season 78’s Sunday Matinée Series generously sponsored by our good friend, author and documentary filmmaker, Mr. Don Hutchison. Please save this date and visit us regularly...

-

Toronto Film Society | January 25, 2026

Toronto Film Society | January 25, 2026

-

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

-

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Donate to Toronto Film Society – We’re now a Registered Charity!

Copyright © 2017 Toronto Film Society.