The End of St. Petersburg (1927)

By Toronto Film Society on March 10, 2017

Toronto Film Society presented The End of St. Petersburg (1927) on Monday, October 22, 1962 as part of the Season 15 Monday Evening Silent Film Series, Programme 1.

La Lettre (France 1938). Produced by Marcel de Hubsch for Atlantic Film. Directed by Jean Mallon. Music by Jean Wiener.

Emak Bakla (France 1927). Directed by Man Ray.

This is one of several dadaist films by the artist and photographer, all of which “aimed at representing aspects of the outer world and seemingly everyday actions in a poetic context by releasing them from all rational logic”. One of Ray’s best-known “rayograms” is briefly seen.

INTERMISSION

The End of St. Petersburg (USSR 1927). Directed by V.I. Pudovkin. Assistant Director: Mikhail Doller. Scenario: N.A. Zarkhi. Photography: A.N. Golovnia. Design: S.V. Koslovski. Production: Mejrabpom-Russ.

Cast: Vera Baranovskaia, A. Christiakov, I. Chiuvelev, V. Obolenski.

The Museum of Modern Art Film Library note says of this film that it is “based on the orthodox Communist view of the War and Revolution rather than on a strictly historical account. if Ten Days that Shook the World is a political cartoon, this is a visual poem on the same theme.”

Paul Rotha wrote in The Film Till Now: “The Government commissioned several films to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the Soviet regime. Ten Days that Shook the World (October) and The End of St. Petersburg were two of the results. Out of their efforts to meet this demand, Eisenstein and Pudovkin built up a form of film technique unequalled for dramatic intensity. Symbolic intercutting is employed as an aid to the emphasis of the central theme, as with the statue of Peter the Great in The End of St. Petersburg. It is a dual theme of symbol and individual, connected mentally by association of ideas, and visually by similarity of the shooting angle. It is found that emotional effect is to be more easily reached by an intercut comparison to a like emotional effect.

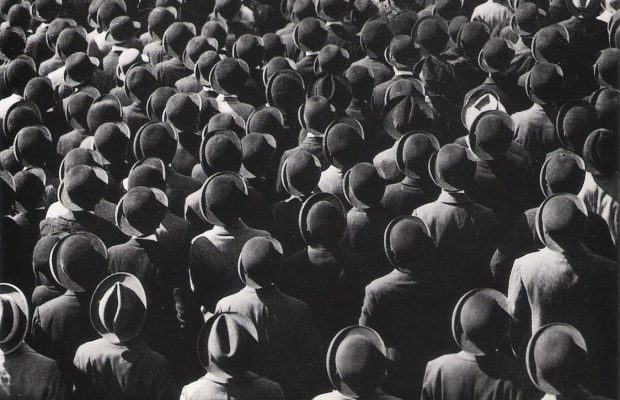

“Contrasted with Eisenstein’s ‘mass’ productions, Pudovkin’s film, which dealt with roughly the same events as October, was an example of individuals moving against a crowded background, of an epic theme seen through individuals. Though a brilliant exposition of the methods of Pudovkin, it had not the intense concentration of his Mother, nor the compelling force, the contact with reality that made the latter so great. The content sought to express the events of the war years, the overthrow of the Czarist regime, the establishment of the People’s Government. In other words, the transition of St. Petersburg to Leningrad. There were two subsidiary themes: the coming of the peasant boy to the city in search of work, his experience in the war; and the story of the old Bolshevik and his wife. An astonishing filmm, composed with the full power of Pudovkin’s filmic mind, at once overpowering and convincing. There were many memorable sequences: the amazing scenes at the outbreak of war; the shots of the war-front cross-cut with those of the stock-exchange; the attack on the Winter Palace. Every sequence was a wonderful example of construction, of the values of cutting and dramatic camera angles; but the film had neither the unity nor the universal understanding of Mother.”

Lewis Jacobs in The Rise of the American Film: “The End of St. Petersburg was so popular that it became the first Soviet film to play in America’s largest theatre, the Roxy, where it ran for several weeks after many weeks of a two-a-day run at Hammerstein’s. Pictorially it had a sweep and richness comparable to Eisenstein, but had less intellectual and structural complexities. Its feeling for the vastness of the Russian countryside, its innumerable satirical touches (the shrieking Kerensky and the pompous police commissioner), its portrait of the bewildered peasant emerging from perplexity to an understanding of the upheaval, are rendered in a quick, sharp style that emphasizes the intensity of the events”.

Bardeche and Brasillach in History of the Film: “Pudovkin’s films are always extraordinarily orchestrated; their construction often empahsized by the use of a dominant theme or the prepetition of themes. In The End of St. Petersburg three conflicting themes are readily identified at the beginning, and united finally with the triumph of the Revolution. We are far from documentary here. All has been selected and ordered: actors, sentiments, settings, lighting and rhythm. Attacking the same subject as October, Pudovkin touches us more deeply than Eisenstein by methods analogous to those in Mother. The revolution is explained to us by the central figure who suffers and rejoices. A theme used often by Soviet directors, in Pudovkin it was full of novelty; the ardor with which he develooped it was a guarantee against any trite or hackneyed element.”

Jay Leyda in Kino: “The End of St. Petersburg was originally planned as an epic film covering two centuries of the city’s history, through Petrograd to Leningrad, but this grand design had to be abandoned. It is the most deliberately symbolistic of Pudovkin’s films. It was full of echoes or tributes to Eisensteins Strike–the elegant automobiles and luxurious waste, the monarch capitalist lonely in the spaces of his office or home (surely Griffith introduced this stylized image in Intolerance, 1916 – GGP), the hysterical typist, the prisoner who enjoys another prisoner’s beating.” Speaking of charges that “graft” had occurred during the production of some of the more elaborate and costly scenes, Leyda says: “these scenes–the flower-bedecked trooping off to war, the elegant assumption of power by Kerensky, were perhaps worth a little graft, for they are among the most striking moments. The artificially induced hysteria that follows the declaration of war in 1914 is one of the most graphic anti-war statements in film; indeed the coments on ‘war’ seem far more meaningful than those on ‘revolution’. The man who made the agonizing battlefield scenes of St. Petersburg had seen both real battlefields and those shown in The Birth of a Nation; but the man who related those scenes to the frantically grabbing scenes at the stock-exchange had stepped intellectually beyond his master, Griffith”.

Two Examples of Pudovkin’s Technique

“By constructive editing it is possible to convey the dramatic content of an occurrence without even showing the actual happening. To render the effect of an explosion in St. Petersburg, he caused a charge of high explosive to be buried and detonated; the explosion was terrific but filmically quite ineffective. So by means of editing, he built an explosion out of small bits of film, taking separate shots of clouds of smoke and of a magnesium flare, welding them into a rhythmic pattern of light and dark. Into this series of images he cut a shot of a river taken some time before, which was appropriate owing to its tones of light and shade. The whole assembly when seen on the screen was vividly effective, but it had been achieved without employing a shot of the real explosion”.

“The glass of hot tea on the table in the worker’s home isnever tasted, no one drinks it–but it serves to measure time by showing the steam coming from it as thinner and thinner; and by itself on the empty table indicates lack of food, poverty; and it’s finally thrown through a window as a danger signal, saving a life!”

Notes compiled by George G. Patterson

You may also like...

-

News

Frances Blau

Toronto Film Society | February 27, 2024On Monday, February 26th, 2024, Toronto Film Society lost longtime friend, supporter, and board member Frances Blau. Known for her sense of humour, her love of film, her generosity,...

-

Special Events

Arsenic and Old Lace (1944) at the Paradise Theatre

Toronto Film Society | April 21, 2024Toronto Film Society presents Arsenic and Old Lace (1944) at the Paradise Theatre on Sunday, May 5, 2024 at 2:30 p.m. Screwball comedy meets the macabre in one of...

Programming

Virtual Saturday Night at the Movies

Toronto Film Society | April 11, 2024Toronto Film Society is back in the theatre! However, we’re still pleased to continue to bring you films straight to your home! Beginning Season 73 until now we have...

4-

Toronto Film Society | April 21, 2024

Toronto Film Society | April 21, 2024

-

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

Toronto Film Society | November 6, 2022

-

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Toronto Film Society | August 1, 2023

Donate to Toronto Film Society – We’re now a Registered Charity!

-

Copyright © 2017 Toronto Film Society.

Leave a Reply