Excuse My Dust (1920) and The Mollycoddle (1920)

Toronto Film Society presented Excuse My Dust (1920) and The Mollycoddle (1920) on Monday, January 23, 1967 as part of the Season 19 Monday Evening Silent Film Series, Programme 3.

(Main Auditorium, UNITARIAN CHURCH, 175 St. Clair West)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Programme No. 3

Monday January 23, 1967

8.15 pm

Part 1: Wallace Reid

1915: Excerpt from Enoch Arden with Lillian Gish (silent speed: 23 min)

1920: Excuse My Dust (Sound speed: 48 minutes)

INTERMISSION

Part 2: Douglas Fairbanks

1920: The Mollycoddle (Sound speed: 65 minutes)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In the year 1920 a popularity contest revealed Wallace Reid, Charles Ray, Thomas Meighan, Eugene O’Brien, Douglas Fairbanks and William S. Hart (in that order) to be the six top male film stars of the day. Two of these stars are being presented on tonight’s program in representative starring vehicles from that year, tailor-made to exploit their personalities, and aiming at nothing more ambitious than light entertainment, attractive to the paying public.

(Neither film therefore is likely to be artistically ruined by being projected anachronistically at 24 frames per second in order to keep our program time within reasonable limits; but bear in mind that all movement will be faster than was seen on the screens in 1920).

This is a double-bill that would never have been seen in 1920. Apart from the historical fact that the double feature program had not yet come into practice, it would have been trumping an ace to have offered two such popular films for the price of one when either one alone would have filled the theatre.

(The Enoch Arden excerpt is obviously out of place on a 1920 program; moreover, it has already been shown in the Silent Series three years ago, on the same bill with Reid’s The Dancin’ Fool. But it comes automatically with Excuse My Dust as part of a package; so since we have it we might as well throw it in as an “added short”; on a program of comedies it makes for “serious” relief.)

* * *

Enoch Arden (excerpt only)

Released by the Mutual Film Corporation, 1915

Based on the poem by Alfred Tennyson

Directed by Christy Cabanné

Supervised by D.W. Griffith

Players: Lillian Gish (as Annie), Alfred Paget (as Enoch), Wallace Reid (as Philip), Mildred Harris

This, of course, is not a Wallace Reid starring vehicle; it predates his stardom by several years, and we find him here in a supporting role. Alfred Paget, who plays the title role, will be remembered as Belshazzar in Intolerance, which was made about a year later. Mildred Harris, only 13 at this time, three years later became Charles Chaplin’s first wife.

This excerpt is approximately the second half of the film. For a modern generation unfamiliar with this once popular narrative poem by Tennyson it may be necessary to fill in the first half. The story, first published in 1864, was set in an English seacoast village “a hundred years ago”, where “…three children of three houses, Annie Lee, the prettiest little damsel in the port, and Philip Ray, the miller’s only son, and Enoch Arden, a rough sailor’s lad made orphan by a winter’s shipwreck” used to play together. As they grew older, both boys fell in love with Annie, but it was Enoch that Annie loved and married. But after a few years Enoch, in order to raise the money to support his family better, signed on as a boatswain on a China-bound merchant vessel, and left for what should have been a year’s absence. It was the last anyone heard from him; the ship never returned, and ultimately (as we see in the film) even Annie reluctantly presumed his death. In actual fact, however, he had escaped drowning, but was marooned on a tropical island for many years, like Robinson Crusoe. (Fo the rest of this thrilling story, see our film exerpt).

Excuse My Dust

A Paramount-Arcraft Picture

Director: Sam Wood

Scenario: Will M. Ritchey

Founded on the Saturday Evening Post story,

“The Bear Trap”, by Byron Morgan.

(A sequel to The Roaring Road, 1919)

Photographed by Alfred Gilks

Art Director: Wilfred Buckland

Copyright by Famous Players-Lasky, Corp., Jan 19, 1920.

In 5 reels.

Dorothy WArd Walden……………………

J.D. WArd, president of the Carco Co…

Tom Darby………………………………..

Max Henderson……………………………

President Mutchler………………………..

Ritz, a daring Fargot driver……………….

Toodles’ little boy…………………………..

Ann Little

Theadore Roberts

Guy Oliver

Otto Brower

Tully Marshall

Walter Long

Wm Wallace Reid, Jr.

It should be emphasized that this was never a super-special prestige picture even in its own day. No ads in 1920 ever touted this as “greater than The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance!” The following review, reprinted in its entirety from Photoplay Magazine for October 1920, offers a contemporary reaction:

I liked Wallace Reid’s Excuse My Dust, first, because it is a good short story, attractively screened, and second, because its creators have not tried to make it anything more than that. One of the eleven or fourteen things we all find to object to in pictures is the obvious effort of scenarioist (SIC) and director, the one usually abetting the other, to build a mansion out of the material laid down for a bungalow. When the thing is finished the foundation is fairly sold, but the superstructure is so very wabbly and thus you can plainly see through it.

Excuse My Dust relates a plausible and interesting incident in the life of “Toodles” Walden, erstwhile demon driver of the good old Darco bus that won the Los Angeles-San Francisco road race in Speed Up. (SIC; SEE BELOW)

No sex stuff here, and no suave young villain. Just a good, interesting, at times exciting, and always well told short story. The ingratiating Wallace Reid is as cheering a screen hero as usual, Theodore Roberts is excellent as the blustering “J.D.”, and Ann Little is a lovable wife.

(NOTE: There was never a film with the title Speed Up; the reviewer is surely referring to The Roaring Road, to which Excuse My Dust is a sequel).

Ann Little will also be remembered as William S. Hart’s leading lady in The Cradle of Courage on our first program of this season–another 1920 film starring one of the top six male film stars of the day.

As we pointed out in our notes for Intolerance, film makers at this period of history felt no artistic compunction about letting subtitles take over the narration of the story whenever this helped speed things along. It will be quickly noticed that the director and/or scenarist of Excusse My Dust tells his story with whatever means lay closest to hand, innocently unaware that it was his duty to be “cinematic” and tell his story entirely by pictures, and that using subtitles to cut corners was simply not playing the game. Even the critic whose review we quoted above doesn’t seem to know enough to reproach him for this. Obviously it was still standard practice in 1920.

* * *

Born March 15, 1892, Wallace Reid was thus 28 years old when this film was made, and as we have already pointed out, he was in that year the most popular male star on the screen. Three years later he was dead, in circumstances unusually tragic.

The story of Wallace Reid can be found in the April 1966 issue of Films In Review, along with a complete list of Wallace Reid’s films, from his first (The Phoenix, 1910) to his 171st (Thirty Days, 1922). The interested reader is referred to this article (and urged to avoid Kenneth Anger’s account in Hollywood Babylon, which sets forth as “fact” all the lurid contemporary rumors).

To summarize it briefly: Wallace Reid’s birthplace was St. Louis, Missouri, but the family subsequently moved to New York. His father, Hal Reid, was a successful actor, director and playwright, and the family lived very comfortably in a Manhattan apartment in the winter and a country estate in New Jersey in the summer. And though his parents separated and eventually divorced, Wallace’s was otherwise never an underprivileged childhood.

In his upper teens he rejoined his father in show business, and in 1910, when he was 18, both of them landed jobs at the Selig movie studios in Chicago, Hal Reid as a scenarist, and his son as a general utility man: filling in as actor, cameraman, etc., as required. For the next few years he worked steadily in films–mostly as an actor but also as writer and director. His 109th film was The Birth of a Nation (1915) in which he played a short but outstanding role as Jeff the blacksmith(he also appeared as Christ in the concluding tableau) which brought him to the attention of Jesse Lasky and Cecil B. DeMille, who quickly snapped him up for their own company (shortly afterwards amalgamated with Zukor’s Famous Players Corp.). (Enoch Arden was his 112th film; his last for the Mutual company was No. 115, Old Heidelberg). DeMille cast him as Don José in Geraldine Farrar’s much-publicized debut film, Carmen (his 116th), and he was Farrar’s leading man in five of her six Lasky films. By 1918 he was a star in his own right, and by 1920 he was the company’s greatest asset. He was the ideal American youth–clean-cut, cheerful, easygoing; admired by men, loved by women, and adored by old ladies and small boys alike.

Jesse Lasky, in his autobiography I Blow My Own Horn, says:

Wallace Reid was the easiest actor to cast and work within the whole of my experience. He had a terrific vogue in automobile-racing pictures–the audiences couldn’t get enough of him behind a steering wheel. We virtually turned these road-racing items out on an assembly line and everyone was a money-maker. But that didn’t type Wally. He was believable in almost every role we gave him.

The first of these “road-racing items” was The Roaring Road, released around March 191. Like all the later ones, it was written by Byron Morgan. The others were Double Speed, What’s Your Hurry? and Across the Continent. Five films out of the twenty-seven that he made from The Roaring Road to Thirty Days, inclusive, hardly suggests an assembly line output, but there’s no denying that the racing car films appealed to the public, who remembered him in these films out of all proportion to their number. (In later years Wallace Reid Jr. whom we see as the little boy in Excuse My Dust, made several films himself, and one of them was an auto racing story written especially for him by Byron Morgan).

Reid seems to have been blessed with an abundance of talents. Not only was he handsome and charming, he seems also to have been intelligent; he was a talented amateur musician, a talented amateur dancer, a talented amateur painter; he was an excellent swimmer and boxer; he could operate any kind of camera; he could not only drive an automobile like a professional, but could repair and reassemble cars himself. In 1913 he had married his leading lady, Dorothy Davenport (whose mother, Alice Davenport, appeared in many of the early Chaplin Keystone pictures, and whose aunt was the famous actress Fanny Davenport), and they had two children and enjoyed a happy domestic life; and at the height of his fame he was drawing a year-round salary of $3000 a week, which wouldn’t look bad even today.

It was all too perfect, and the gods eventually took notice and struck. In 1919, during the filming of The Valley of the Giants, the train carrying the company on location to the High Sierras was involved in a wreck, and Reid received head and spinal injuries which healed quickly enough but resulted in blinding headaches, and he was given morphine injections to relieve the pain and enable him to continue acting before the cameras. Doctors knew a lot less about narcotics in those days or they would have stopped the injections sooner; instead, his system became addicted to the drug.

The rest of his life was a secret and losing battle against the addiction. The strain of the struggle literally drove him to drink, which of course only made things worse. By the latter part of 1922 his health was so undermined that at one point during the making of Thirty Days he collapsed; and when the film was finished the studio declared that it could not risk beginning a new one. Reid at last stopped fighting alone, and entered the Banksia Place Sanitarium. “I’ll either come out cured or I won’t come out at all!” he declared.

Mrs. Reid then did a very wise thing. She called the press to her home and gave them the true facts–partly to circumvent distorted rumors, but also for the avowed purpose of alerting the public to the dangers of drug addiction. The press respected this honesty, and the first newspaper accounts were dignified and sympathetic (though unfortunately later ones were lurid and sensational), and the public too was sympathetic. It is a measure of the respect in which Reid was held that, in order to prevent him from learning that the public knew about his condition, the Los Angeles Examiner voluntarily printed a special copy for delivery to Reid in which the story had been deleted.

Early in January 1923 his health began improving and he even regained a few pounds; but he was not strong enough to combat an attack of influenza, and he died on Thursday January 18, 1923. He was not yet 32 years old.

* * *

The Mollycoddle

Released by United Artists

Director: Victor Fleming

Story: Harold McGrath

Scenario: Tom J. Geraghty

Copyright by the Douglas Fairbanks Picture Corp.

June 15, 1920. In 6 reels.

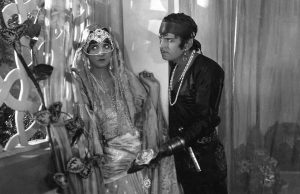

Players: Douglas Fairbanks, Ruth Renwick, Wallace Beery.

The career of Douglas Fairbanks Sr (born Denver 1883, died Hollywood 1939) falls into two divisions; the Broadway stage (1905-1915) and the motion picture screen (1915-1934). It was on the strength of his great popularity as a stage star that he was signed by the Triangle Film Corporation in 1915–along with numerous other outstanding stage stars of the day, most of whom were complete failures in films. Fairbanks was the most notable exception; his screen success quickly eclipsed his stage career–though there were those who always insisted he was a far better actor in his stage days that he ever was on the screen.

His screen career divides itself into three distinct periods:

#1: 1915-1920. In which he won enormous popularity as the bright, breezy, go-getting young American, and turned out a total of 30 feature comedies tailored to his ebullient and athletic personality.

#2: 1920-1929. Dropping the modern American character, he produced the eight large-scale costume pictures for which he is now best remembered: The Mark of Zorro, The Three Musketeers, Robin Hood, The Thief of Bagdad, Don Q, The Black Pirate, The Gaucho, and The Iron Mask.

#3: 1929-1934. With the coming of sound he dropped this type of role and made five varied films (beginning with The Taming of the Shrew) with rapidly waning enthusiasm, received similarly by the public.

Periods 1 & 2 overlap slightly because The Mask of Zorro seemed such a complete departure from his tried and true formula (actually it wasn’t, but putting it into a historical setting was) that as soon as it was finished but before it was released, Fairbanks began another of his typical modern comedies, The Nut. But The Mark of Zorro turned out to be by far his most popular picture to date, and its success confirmed him in his new direction. The post-war decade had begun, and America’s era of breezy optimism was over.

On each of our past three season, the Silent Series has presented a Doug Fairbanks picture from the middle period: The Thief of Bagdad (1924), The Mark of Zorro (1920) and Don Q, Son of Zorro (1925). This year, for a change, we are presenting a film from his first period. The Mollycoddle was the last film made before The Mark of Zorro, and hence is No 29 of the 30 films of Period 1.

Douglas Fairbanks was 32 years old when he was lured away from Broadway to Hollywood by the incredible and irresistible salary of $2000 a week. His final play, “The Show Shop”, ended its run on May 15, 1915, and he left for the West Coast to fulfil his contract with Triangle.

The Triangle company had just recently been formed by the banding together of the production companies of D.W. Griffith, Mack Sennett and Thomas Ince. Fairbanks’ first film for them was The Lamb, an adaptation of his stage success “The New Henrietta”. The ebullient, irresponsible Fairbanks, whose excess energies were perpetually spilling over into almost unceasing athletic displays–on-camera as well as off–did not appeal to Griffith, who was supervising the production of The Lamb; Griffith seriously felt that Fairbanks would do much better under Sennett–a suggestion that didn’t appeal to Fairbanks, who considered he was demeaning himself quite enough by appearing in pictures at all. Fortunately, some shrewd person or persons saw to it that he got together with two other Triangle employees: scenario writer Anita Loos (future author fo the novel Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and of the recently published autobiography A Girl Like I) and director John Emerson, who soon saw how the exuberant Fairbanks off-stage personality could be exploited on the screen.

Much to everyone’s surprise, The Lamb proved a hit, and Fairbanks was turned over to the Loos-Emerson team, which produced 12 films in as many months, to the end of 1916. So popular were these films that by that time Fairbanks was drawing a salary of $10,000 a week. But even this wasn’t enough for him, so instead of renewing his contract with Triangle, he and his brother formed the Douglas Fairbanks Pictures Corporation to make his own films and thus keep all the profits himself. The films were released by Famous Players-Lasky (Paramount) under their Artcraft label (cf. Excuse My Dust). From Triangle he brought his collaborators, John Emerson and Anita Loos, and (working at a slower pace) they turned out another twelve pictures over the next two years. In 1919 Fairbanks, Pickford, Griffith and Chaplin (“the Big Four”) formed their own distributing company, United Artists Corporation, which handled all their films thereafter. Fairbanks continued to slacken his pace–he produced only three films a year in 1919 and 1920; and once into Period 2 his output averaged less than one a year–but each one a “special”.

The thirty films of Period 1 (of which only a few–including The Mollycoddle–were not written by Anita Loos and directed by John Emerson) were, in general, simply variations on a single theme: the brash, enthusiastic young “100% American”, brimming over with vigor and optimism and know-how,–“Mr. Average Man with powers of Superman”–triumphing over all obstacles. So suitable was this formula to his personality, and vice versa, and to the times, that by 1920 he was one of the most loved stars of the screen, not simply in North America but all over the world. In March of that year he married the screen’s most popular actress, Mary Pickford, a romance enthusiastically endorsed by the delighted public (in spite of the fact that both had had to divorce their current mates to make it possible–a more grievous offense then than nowadays). Their honeymoon in Europe was like a Royal Tour.

The Mollycoddle, then, belongs to the latter end of this period, and was made around the time of his wedding to Mary Pickford–either just before or jut afterwards. We regret that we don’t have a contemporary review of this film, from which to learn how it was rated at the time in comparison with his earlier films; and not having seen the film yet ourselves we cannot offer any first-hand observations or comments. The MMA catalogue simply says “During the first five years of his career, Fairbanks made great play with the character of a rich Eastern weakling transformed by the strenuous life. Here, in its most extreme form, he is a Europeanized playboy who retraces the spiritual progress of his ancestors”.

But we should add a word about the “land yacht” that figures in the film. Doug’s brother Robert, who was his production manager, had been an engineer, and thus proved very useful in dreaming up gadgets like this. This forerunner of the modern trailer was built for the picture at a cost of $20,000–but don’t let that fool you; it was still only a prop. It could indeed travel under its own power, but only for about fifty feet, and very slowly. It is trick photography that makes it go whizzing by at top speed.

(The interested reader is referred to Douglas Fairbanks: The Fourth Musketeer by Ralph Hancock and Letitia Fairbanks, from which most of the foregoing information comes–including the paragraphs we lifted from our own program notes for The Thief of Bagdad, TFS Silent Series January 13, 1963).

* * *

POSTSCRIPT to the notes for Intolerance (Nov 21, 1966)

The Museum of Modern Art, in its published list of the complete cast of Intolerance, has for over a quarter of a century listed the celebrated dancer, Ruth St Denis, as the Solo Dancer in that film. But when we came to write the notes for Intolerance, we found ourselves in a situation familiar to all program note writers: we were sure that we had read somewhere that in actual fact Ruth St Denis was not in the film–but we were unable to reconfirm this impression because we had lost all recollection of where we had read it. The best we could do was pass along the MMA’s information firmly hedged about with a query indicating doubt, and appealing for confirmation.

We received two answers (coincidently, both arrived on the same day) which assured us that our memory hadn’t played us false. First of all, Louise Brooks reminded us that it was she who had told us the story in conversation, several years ago. “Not only to you but to a dozen writers have I explained that Miss Ruth was not in the film. But either because they like to be detectives, or name-droppers, or never wrong, they never correct this mistake. It is hopeless to buck the inventions of Iris Barry”.

Here is Miss Brooks’s account:

Having danced with Ruth St Denis and Ted Shawn for two years (1922-23 and 1923-24), when I was writing an article. “Word and Movement in Film”, in 1961, I wrote Mr Shawn to find out whether this wild assumption that Miss Ruth appeared in Intolerance had any truth in it. Mr Shawn wrote me that it wasn’t true. Here is the truth and far more fascinating than invention. In 1915 Miss Ruth and Mr Shawn opened the Denishawn school in Los Angeles. Mr Griffith, who understood that movement was the essence of film acting, sent Lillian Gish to study there. Her spiraling anguish in the closet scene of Broken Blossoms was learned from Miss Ruth. Griffith found Carol Dempster at Denishawn. Seena Owen studied with Miss Ruth and copied her Egyptian make-up and costume so perfectly that I shall not be surprised to read in another ten years that Seena is really Miss Ruth in Intolerance. Mr Shawn wrote that Griffith wanted Miss Ruth and him to dance and to direct the ballets in Intolerance, but the deal fell through because Griffith could not “meet their fee”. Whereupon Griffith used students of Denishawn who worked extra in all his pictures. And, like Seena, the “Solo Dancer” made up and dressed like Miss Ruth. A final comment on screen detectives is this: Why haven’t any of them ever spotted Charles Weidman in a mad scene in Orphans of the Storm? Next to Martha Graham and Doris Humphrey, he was the most famous of Deishawn dancers.

In the same mail came a letter from one of our Silent Series members, Cora Hartwell, who, in response to the appeal I uttered in the Intolerance notes, wrote directly to Ted Shawn himself, and passed along to me a copy of his reply to her:

Your enquiry is one that I and Ruth have answered thousands of times during these fifty years since Intolerance was produced, and our answer has been a complete and categorical denial–we neither of us appeared in the film, nor any of our dancers that we know of–in any event if any of our dancers did appear it was without our knowledge at the time. We saw the film, and repudiated the dancing artistically, and did not want, in any way, to have our names associated with it–as in fact neither of us appeared, and did not “choreograph” or direct the dancing.

If you can so advise the people who showed the film–using Miss St Denis’s name in any way is a falsehood and should be stopped! I do not even know who the dancers were!

During that period, I worked with many directors and supplied dancers, and choreographed many dance sequences in films but never worked with D.W. Griffith.

The message seems to be clear and unmistakable. Ruth St Denis did NOT appear in Intolerance. Future historians please copy.

(Neither of my correspondants pointed out that I had misspelled Miss St Denis’s name. That error was my own, not the MMA’s).

* * *

Incidently, Miss Brooks tells us that an article by her on Humphrey Bogart is due to appear in the Winter edition of the film quarterly, Sight and Sound. TFS members will all want to watch out for it. (Miss Brooks, in case you didn’t know, is one of the official Patrons of Toronto Film Society)

Notes by Fraser Macdonald

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Next meeting of the TFS Silent Series: Monday February 27, 1967. Those of you who enjoyed René Clair’s Les Deux Timides on the Main Series recently will not want to miss his previous film, The Italian Straw Hat (1927). It will be an all-French program, rounded out with two short films made twenty years prior to that: Ferdinand Zecca’s Fun After the Wedding (1907) and Georges Méliès’ The Doctor’s Secret (1908).

Leave a Reply