Hell on Frisco Bay (1955)

Toronto Film Society presented Hell on Frisco Bay (1955) on Monday, July 9, 2018 in a double bill with The Devil Thumbs a Ride as part of the Season 71 Summer Series, Programme 1.

Production Company: Jaguar Productions (Warner Bros. distribution). Producer: George C. Bertholon. Director: Frank Tuttle. Screenplay: Sydney Boehm and Martin Rackin, from the novel “The Darkest Hour” by William P. McGivern. Cinematography: John Seitz. Film Editor: Forlmar Blangsted. Music: Max Steiner. Release Date: December 1, 1955.

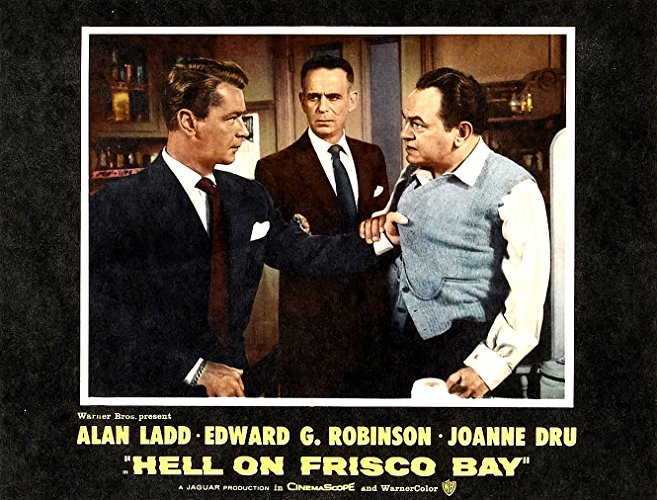

Cast: Alan Ladd (Steve Rollins), Edward G. Robinson (Victor Amato), Joanne Dru (Marcia Rollins), William Demarest (Dan Bianco), Paul Stewart (Joe Lye), Perry Lopez (Mario Amato), Fay Wray (Kay Stanley), Renata Vanni (Anna Amato), Nestor Paiva (Louis Fiaschetti), Stanley Adams (Hammy), Willis Bouchey (Police Lt. Paul Neville), Peter Hanson (Detective Connors), Anthony Caruso (Sebastian Pasmonick), Rodney Taylor (John Brodie Evans), Jayne Mansfield (Mario’s Dance Partner at Nightclub), Mae Marsh (Mrs. Cobb, Steve’s Landlady).

Alan Ladd was experiencing health issues prior to making Hell on Frisco Bay. Besides the aging process affecting his self-esteem, he had to postpone making the film until he recovered from the chicken pox. Then just before the end of filming, Ladd caught his foot in the cable of a boat with Edward G. Robinson shouting a warning preventing him from being seriously hurt. But unfortunately, this was the beginning of freak accidents, illnesses and an enervating chain of self-destructive mishaps. Still, Hell on Frisco Bay gained a minor reputation as an enjoyable throwback—a fifties film with all the verve of its thirties counterpart, causing Ladd fans to regret that he chose not to revive his street-wise tough guy more often in his last decade of stardom.

Meanwhile Edward G. was having personal troubles of his. His son was in the midst of getting divorced and was in trouble once again with the law, Robinson’s wife Gladys was having psychological episodes and was once again demanding for a divorce. To paraphrase Robinson’s memoir, taking on this role was easy but his life could have been titled “Hell in Beverly Hills”.

However, the reviews that Robinson received were all good. Bosley Crowther of the New York Times wrote that, “Every time Mr. Robinson slouches upon the scene, gnawing cigars and slobbering cynicisms, it is amusing, interesting—and good”, while William K. Zinsser of the New York Herald-Tribune stated, “This is the old meanie at the top of his form, relishing every black minute of his role.”

Sadly, during the filming a tragedy occurred. Luis Tomei, race driver and movie stunt man, died on May 15, 1955 in Cedars of Lebanon hospital of a head injury he received doubling for Robinson in a fight scene being filmed on San Francisco Bay. Tomei apparently was hurled against a metal fitting of the boat he was on, suffering a severe head injury. He was brought back to Los Angeles for hospitalization but died without having ever regaining consciousness. Tomei was widely known in western auto racing, having competed in short track racing during the early 1930s.

Sources: Chicago Tribune, May 17, 1955, page 55; The Cinema of Edward G. Robinson by James Robert Parish and Alvin H. Marill (1972); All My Yesterdays: An Autobiography by Edward G. Robinson with Leonard Spigelgass (1973); Ladd: A Hollywood Tragedy by Beverly Linet (1979); The Films of Alan Ladd by Marilyn Henry and Ron DeSourdis (1981)

Introduction by Caren Feldman

By 1955, Alan Ladd had already climbed to the top of Paramount—he had the pictures to prove it. His famous pairings with Veronica Lake; a couple dozen western, adventure, and war films; and his iconic role in Shane had cemented his status as a bankable tough-guy, popular with both ladies and gents. Thirteen years after he broke out, his face may have displayed a bit more middle-aged thickness and his contract with Paramount may have been in the rearview mirror, but, intent on controlling his destiny, he had formed his own Jaguar Productions. It was the safest way to maintain a regular slate of pictures while being in charge of what story material was chosen and the cast and crew that surrounded him. Besides creative control, owning a share of the profits through distribution deals with major studios (for the vast majority of the projects it was Warner Bros.) meant more money both up front and down the road. This mature, businesslike sense informs every aspect of Jaguar’s second film (following the Delmer Daves helmed western Drum Beat), Hell on Frisco Bay, a cops and gangsters movie that could have been studio fodder anytime in the preceding 25 years. To wit, Edward G. Robinson plays the lead heavy, mob boss Victor Amato, a casting choice as safe as giving a bloodsucker role to Bela Lugosi. (Although James Cagney was the initial choice for this role, the point still stands.) When it comes to producing pictures, familiarity breeds a healthy profit.

Speaking of sticking to one’s stock in trade, novelist William P. McGivern made an industry of stories of cops gone off the straight and narrow. McGivern’s novels provided blueprints for several Eisenhower-era crime films: Glenn Ford dispensing justice in Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat (1953); Edmond O’Brien’s corruption in Shield for Murder and Robert Taylor in the role of a slick grafter with a badge in Rogue Cop (both 1954); while Ed Begley’s ex-cop is the least of a sorry lot in Odds Against Tomorrow (1959). McGivern penned “The Darkest Hour” in 1954 and the film rights were snatched up by Ladd before the ink had dried. No doubt, Ladd could easily envision himself as protagonist Steve Retnick (changed to Rollins in the film), an ex-cop whose five-year sentence in Sing Sing on a trumped-up manslaughter charge had carved his mind down to the solitary thought of revenge. Ladd enlisted screenwriters Sydney Boehm and Martin Rackin to tackle the adaptation. Again, choosing these writers was a safe bet: Boehm had already written The Big Heat and Rogue Cop, among many other crime films, and Rackin had scripted the Bogart-against-the-mob film The Enforcer (1951).

The direction of the picture was assigned to Frank Tuttle, whose This Gun for Hire (1942) had lifted Ladd from the proverbial cellar of (mostly) uncredited roles in B-films. This reunion, a two-picture deal with Jaguar, allowed the veteran Tuttle a chance to rebound after a string of flops. It was a warm gesture to hand the reigns over to a man who had been in the industry since the silent era. After his second Jaguar film, the Edmond O’Brien-starring A Cry in the Night (1956), Tuttle would only direct one more film before his death in 1963 at the age of 70. Rounding out this crew of consummate professionals are cinematographer John F. Seitz, who had photographed Ladd through his prime, including This Gun for Hire (1942); Calcutta (1947); Saigon (1948); The Great Gatsby (1949); and Chicago Deadline (1949). He would continue as a staple of the Jaguar crew. Costume designer Moss Mabry had just months earlier made his mark on pop culture history by adorning James Dean in a red nylon windbreaker. And mention must be made of Max Steiner, who contributes an appropriately sonorous score.

Supporting Ladd and Robinson are a cast of familiar mugs, including former member of Orson Welles’ Mercury Theatre, Paul Stewart (who lent his sinister presence to Kiss Me Deadly the same year); Preston Sturges’ regular, William Demarest; and a young Rod Taylor (billed here as Rodney). If the names Willis Bouchey or Anthony Caruso are not familiar, I guarantee their weathered faces are. Joanne Dru most likely enjoyed being in a non-western, and her scenes singing in the film’s swanky midnight-blue nightclub The Lookout Room provide nice respites from the bouts of fisticuffs. Fay Wray plays a film actress washed up at the ripe old age of 35. Her tête-à-tête with Edward G. Robinson is the most charged scene in the movie (“You filthy peasant!”), as it flays the gangster, entirely exposing his sexual repression and antipathy towards his devout Roman Catholic wife. Keep a look out for Mae Marsh, stock player for both D.W. Griffith and John Ford, as Steve’s starstruck landlady. It’ll be harder to miss an uncredited Jayne Mansfield as a ditzy blonde (what else?) who gets pummeled by a couple of spicy quips.

For a movie with a grim subject, there’s an oddly comforting familiarity to every aspect of Hell on Frisco Bay: The crisp Cinemascope/Warnercolor photography; the mixture of authentic San Francisco locations and obviously stage-bound sets (I particularly love seeing the flashing Southern Pacific railroad sign—“SP”—in the miniature skyline); and the veteran cast hitting all their marks. It’s difficult to imagine that it was in theatres at roughly the same time as On the Waterfront (1954) and Rebel Without a Cause (1955)—two films that undoubtedly forged the style of the coming years—as it seems worlds away from the grittiness of the former and the histrionics of the latter. It’s a movie that harkens back to the Golden Age.

Notes by Adam Williams

Leave a Reply