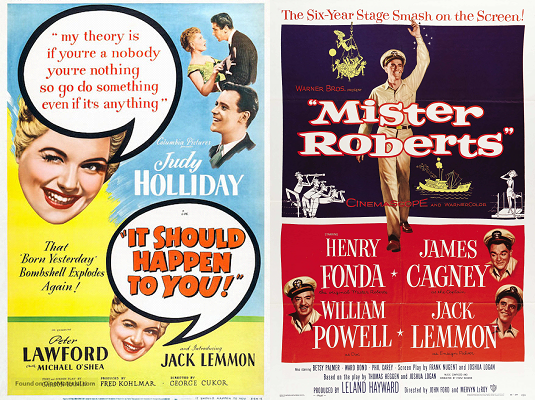

It Should Happen to You (1954) and Mister Roberts (1955)

Toronto Film Society presented It Should Happen To You (1954) on Sunday, November 2, 1986 in a double bill with Mister Roberts (1955) as part of the Season 39 Sunday Afternoon Film Buffs Series “A”, Programme 3.

It Should Happen to You (1954)

Production Company: Columbia. Producer: Fred Kohlmar. Director: George Cukor. Screenplay: Garson Kanin. Photography: Charles Lang. Editor: Charles Nelson. Art Direction: John Meehan. Music: Frederick Hollander. Costumes: Jean Louis. Release Date: January 15, 1954. Nominated for 1 Oscar, for Best Costume Design.

Cast: Judy Holliday (Gladys Glover), Peter Lawford (Evan Adams III), Jack Lemmon (Pete Sheppard), Michael O’Shea (Brod Clinton), Vaughn Taylor (Entrikin), Connie Gilchrist (Mrs. Riker), Walter Klavun (Bert Piazza), Heywood Hale Broun (sour Man), Constance Bennett, Ilka Chase, Wendy Barrie, Melville Cooper (themselves).

Mister Roberts (1955)

Production Company: Orange Productions-Warner Brothers. Producer: Leland Hayward. Directors: John Ford, Mervyn LeRoy, Joshua Logan. Screenplay: Frank Nugent, Joshua Logan, from the play by Joshua Logan and Thomas Heggen, and the novel by Thomas Heggen. Photography: Winton C. Hoch, in Warnercolor and Cinemascope. Art Direction: Art Loel. Set Decoration: William L. Kuehl. Music: Franz Waxman. Orchestrations: Leonid Raab. Editor: Jack Murray. Assistant Director: Wingate Smith. Exteriors filmed in the Pacific. Released: July 30, 1955. Nominated for 3 Oscars, including Best Picture. Winner for Best Supporting Actor, Jack Lemmon.

Cast: Henry Fonda (Lt. Roberts), James Cagney (Captain), Jack Lemmon (Ensign Frank Thurlowe Pulver), William Powell (Doc), Ward Bond (C.P.O. Dowdy), Betsy Palmer (Lt. Ann Girard), Phil Carey (Mannion), Nick Adams (Reber), Harry Carey, Jr. (Stefanowski), Ken Curtis (Dolan), Frank Aletter (Gerhart), Fritz Ford (Lidstrom), Buck Karalian (Mason), William Henry (Lt. Billings), William Hudson (Olson), Stubby Kruger (Schlemmer), Harry Tenbrook (Cookie), Pat Wayne (Kookser), Tige Andrews (Wiley), Jack Pennick (Marine Sergeant).

Both Gladys Glover in It Should Happen to You and Lt. Doug Roberts in Mister Roberts were common folk who, afraid life was passing them by, grasped at a last chance to do something. Gladys Glover, an actress whose ambition exceeded her talent, spent all her savings on leasing a Columbus Circle billboard and spelling her name on it in gigantic letters. Garson Kanin originally wrote the film as a vehicle for Danny Kaye, but soon changed it to fit Holliday’s peculiar talents. Kanin, who also wrote Holliday’s Oscar-winning role in Born Yesterday, fashioned the film after the screwball comedies of the 1930s, particularly True Confession and Nothing Sacred. Incidentally, the original title, A Name For Herself, seems a much more apt title than It Should Happen to You.

Jack Lemmon was a young TV actor on contract to Columbia when he made It Should Happen to You, which John Ford saw. Lemmon walked on the Columbia set of The Long Gray Line, which Ford was filming in early 1954. Ford walked up to the young actor and said, “Aren’t you Jack Lemmon?”

Lemmon surveyed the gnarled figure dressed in a rumpled fatigue jacket with a baseball cap set low on his forehead. He looked vaguely familiar. Probably some grip who worked around the lot.

“Yeah, said Lemmon.

“I’ve been watching you. You’re pretty good.”

“Thank you,” said Lemmon, humoring the old guy.

“You familiar with Mister Roberts?”

“Of course.”

“You’d make a helluva good Ensign Pulver.”

“Tell that to John Ford, will you?”

“I am John Ford, and you are Ensign Pulver. Shooting starts in Honolulu in September.”

Lemmon stood there slack-jawed as John turned around and went back to his work on The Long Gray Line. (Reported by Dan Ford)

Mister Roberts was one of the greatest successes in Broadway history, and Henry Fonda became absolutely identified with the role, playing it over 1600 times on Broadway and on tour. Fonda had been away from movies almost seven years when it was time to film Mister Roberts, and Warner Brothers, who owned the screen rights, offered the lead to William Holden, then a recent Oscar-winner and the hottest actor in films. Holden turned it down on moral grounds with the belief that Fonda ‘owned’ the part of Lt. Roberts. Still believing that Fonda was too old and that the public had forgotten him, Warners gave the part to Marlon Brando, then the next biggest star in movies, having just been universally acclaimed for On the Waterfront. Brando actually accepted the role. But in the meanwhile, John Ford had been signed to direct the film,and Ford, remembering the many brilliant performances Fonda gave him in such masterpieces as Drums Along the Mohawk, Young Mr. Lincoln, The Grapes of Wrath, My Darling Clementine and Fort Apache (1948, and Fonda’s last starring role before his long sojourn on Broadway), insisted on Fonda for Mr. Roberts.

Warners wanted the stage play opened up for the screen and thus sought naval cooperation to film at naval bases and with naval ships. The navy refused, on the grounds that ‘the Captain’ character was detrimental to the navy image. Ford, who still had enormous influence with the navy due to his extraordinary work during WWII, simply went to the chief of naval operations and the navy immediately relented, giving Warners the use of cargo ship U.S.S. Hewell, and permission to film at naval bases at Midway and Hawaii.

Warners wanted the stage play opened up for the screen and thus sought naval cooperation to film at naval bases and with naval ships. The navy refused, on the grounds that ‘the Captain’ character was detrimental to the navy image. Ford, who still had enormous influence with the navy due to his extraordinary work during WWII, simply went to the cheif of naval operations and the navy immediately relented, giving Warners the use of cargo ship U.S.S. Hewell, and permission to film at naval bases at Midway and Hawaii.

When Frank Nugent (Ford’s son-in-law and former star film critic at the New York Times) and Ford began work on the script they decided to make the humour of the play more physical, more slapstick. This worried Fonda, who feared the subtlety of the play would be lost. Fonda and Leland Hayward felt the play should be filmed so that what worked on stage would work on film. Fonda later said: “Playing Mr. Roberts on the screen started out as a dream come true for m. After all those years I would be back with Pappy. He was the right man for it for every reason that I could think of. H was a navy man, a location man, and a man’s director. He was a giant in the business, and when he was on the battery nobody could touch him. I think that I can say that after all our years together we were a love story. He loved me just like he loved Duke and Ward. Still, I was uneasy about the changes he was making. As far as Leland and I were concerned, there was only one way to do things, the way we had done them in the play. I can remember laying awake at night wondering what Pappy was going to do with this property which had been so successful for so many years. How was he going to film it? What changes was he going to make? I had forgotten that Pappy was an egomaniac, and Irish egomaniac as well.”

Fonda continued: “I guess I was just a purist about the play. Maybe it was my fault, but I had played it for seven years, and I had very strong opinions about it. I didn’t like the kind of roughhouse humor that Pappy was bringing to it. I knew where the laughs were, and I knew the timing. The scene where the crew is looking through binoculars and they see the nurses taking their shower was one of the funniest in the play. But Pappy shot it all wrong. He didn’t know the timing. He didn’t know where the laughs were and how long to wait for them to die down. He had them all talking at once, throwing one line in on top of another. When I said something he just handed me the script and said, ‘Here, you wanna direct?'”

One evening when Fonda complained about what he thought Ford was doing wrong, Ford got up and slugged Fonda, knocking him backwards onto the floor. Ford, always an Irish drinker, started drinking during production, and later had a gall bladder operation that resulted in his removal from the film. Mervyn LeRoy was brought in and tried to shoot the picture as he thought Ford would have wanted. Joshua Logan then finished directing and directed the editing.

For an interesting attempt at separating these efforts, we have Tag Gallagher’s description in his book, John Ford: The Man and His Films: “Ford shot most of the exteriors, but there are few of these, and many of them are integrated with studio work, so that there are virtually no significant sequences of Fordian cinema, with the editing Ford intended. His segments are recognizable by their faster tempo, spiffier style, greater physicality, and more inventive employment of space. The LeRoy segments–long, sparsely edited, talky, and static–lack visual interest and resemble a filmed play, as Fonda wished. Ford can be distinguished during the nurses’ visit; in the altercation (in crosscuts) between Fonda and James Cagney over shirtless sailors; and in individual shots of the Liberty Port sequence. Ford evidently intended a speedier, many-charactered portrait of a crew, and more ambivalence about duty and obedience. His Roberts, in contrast to the fairly simple one of LeRoy and Fonda, would have enriched contradictions: his druggy pomposity and thirst for glory that make him prefer to be the crew’s hero rather than an effective intermediary. Ford had wished to eliminate the scotch-making and the laundry scenes–which Joshua Logan directed after LeRoy left. Some of the slapstick comedy Ford inserted–such as the drunk sailor riding a motorcycle off a pier–was cut out by Fonda and Hayward and then restored by Warners.”

A final resolution to the dispute of who directed what or how much will probably never occur. Compare Ford’s comments: “I got a gall bladder attack towards the end of shooting, but I did most of the picture. A lot of that forced comedy inside the ship wasn’t mine. A lot of my stuff was cut out by the producer, Leland Hayward, because it wasn’t in the original play. Then Josh Logan, who wrote the play, looked at the stuff that had been cut and he said, ‘This is funny stuff, for Pete’s sake,’ and insisted on putting a lot of it back in.”

Yet Mervyn LeRoy’s version differs more than slightly: “After he (Ford) had been working a week or so, something happened…They called me that Sunday morning and then they came over to see me and brought the shooting script…The original play, as I had seen it in New York and read it the night before was far superior to the script Ford had been using…I would estimate that I shot 90 percent of the finished product. I insisted, however, that the credits read: “Directed by John Ford and Mervyn LeRoy.’ They told me it wasn’t necessary to give Ford credit, but I felt it was a nice gesture to make.”

Notes by Jaan Salk

Leave a Reply