Lonely Are the Brave (1962) and Hud (1963)

Toronto Film Society presented Lonely Are the Brave (1962) on Monday, April 6, 1987 in a double bill with Hud (1963) as part of the Season 39 Monday Evening Film Buffs Series “B”, Programme 9.

Lonely Are the Brave (1962)

Production Company: Universal/Joel (Kirk Douglas) Productions. Producer: Edward Lewis. Director: David Butler. Screenplay: Dalton Trumbo, from the Novel Brave Cowboy by Edward Abbey. Cinematography: Philip Lathrop. Editor: Leon Barsha. Music: Jerry Goldsmith. Assistant Directors: Tom Shaw and David Silver. Art Direction: Alexander Golitzen, Robert E. Smith.

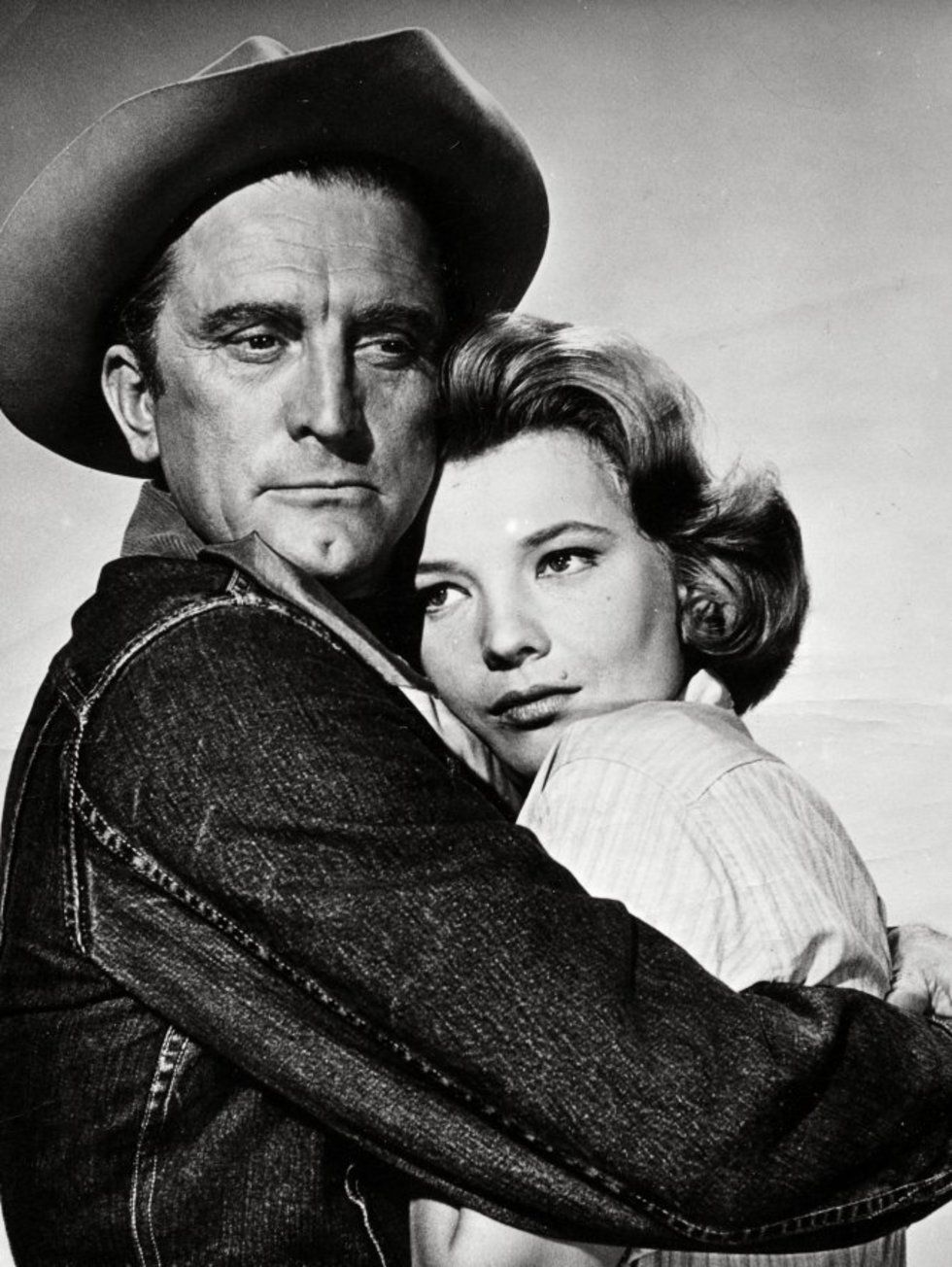

Cast: Kirk Douglas (Jack Burns), Gena Rowlands (Jerri Bondi), Walter Matthau (Sheriff Johnson), Michael Kane (Paul Bondi), Carroll O’Connor (Hinton), William Schallert (Harry), Karl Swenson (Rev. Hoskins), George Kennedy (Gutierrez), Dan Sheridan (Deputy Glynn), Bill Raisch (“One Arm”).

Hud (1963)

Production Company: Paramount. Producers: Martin Ritt, Irving Ravetch. Director: Martin Ritt. Screenplay: Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank, based on the novel Horseman, Pass By, by Larry McMurtry. Art Direction: Hal Pereira, Tambi Larsen. Musical Score: Elmer Bernstein. Cinematography: James Wong Howe. Special Photographic Effects: Paul K. Lerpac. Editor: Frank Bracht.

Cast: Paul Newman (Hud Bannon), Mervyn Douglas (Homer Bannon), Patricia Neal (Alma Brown), Brandon de Wilde (Lon Bannon), Whit Bissell (Burris), John Ashley (Hermy), George Petrie (Joe Scanlon), Sheldon Allman (Thompson), Carl Low (Kirby), Don Kennedy (Charlie Tucker).

Tonight we see, at the height of their powers, two of the most important American film actors of the third quarter of the century. Kirk Douglas was born nearly a decade before Paul Newman, and came to stardom in the late ’40s, Newman in the late ’50s. Douglas’s first major appearance was in the title role of Champion, and the parts that he played for the next thirty years were of a piece with that role, men of individuality, for good or ill. At worst, egocentric semi-psychopaths, as in Ace in the Hole and The List of Adrian Messenger. At best, and more often, the egocentricity becomes conscience and principle–the incorruptible policeman of Detective Story, the junior officer at odds with his generals of Paths of Glory and Seven Days in May, the American patriot fighting the British governors of The Devil’s Disciple. The quintessence of the Douglas persona is contained, on the one hand, in the totally self-centred producer of The Bad and the Beautiful and, on the other, in the slave whose individualism cannot be tamed, in Spartacus.

The Newman persona is similar, yet more relaxed, his individualism less that of pathological egocentricity, his outsider qualities less tortured, more genial than Douglas’s. Coll Hand Luke rather than Vincent Van Gough; Billy the Kid rather than Doc Holliday. While Douglas is found most often working within the system for change (and beating his head against a brick wall), Newman is more often the drifter, the man who moves on, avoiding annihilation, when the accommodation fails. (The novels on which these two pictures are based rather aptly suggest the difference as well–Brave Cowboy versus Horseman, Pass By). While both Douglas and Newman studied acting, Newman studied at the Actors’ Studio, where he was taught by Martin Ritt, with whom he would make several of his films; and his stage career was more auspicious. His first role on Broadway was that of the drifter in William Inge’s Picnic (the part played by William Holden in the picture), and he went on to play like roles in such films as The Long Hot Summer (for Ritt), Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (his one notable tortured role, for which he is much less suited than Ben Gazzara), and The Hustler. The quintessence of the Newman persona is there, and in Butch Cassidy.

Douglas’s performances tend to be more internalized than Newman’s, despite the latter’s training in “method” acting; and this difference is reflected in the directors for whom they worked. Douglas made his film debut with Lewis Milestone, a director of the internal world of his characters, and he made his best films for directors just as psychologically attuned: Wilder, Mankiewicz, Huston. Newman made his first important film for Robert Wise, the blandest of the bland, and went on to work for Martin Ritt, Leo McCarey, Mark Robson, all directors more concerned with surfaces than internalities. Could one imagine Hitchcock directing Douglas, or Kubrick directing Newman?

Tonight’s two films embellish these differences between the two personas, Lonely Are the Brave presenting Douglas as the last individualist, broken by the society of technology, and Hud presenting Newman as the oblivious outsider, whom the society simply abandons, leaving him to go his own way. Both films, too, are Westerns of a sort, and seen as such they show how the values embodied in the frontier have become tarnished and irrelevant a century after the opening up of the West. By the 1960s, even the Master was turning away from the Westerns: of John Ford’s last six films only three deal literally with the American West, and those three are distinctly elegiac; The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, with its “Print the legend,” appeared at much the same time as Lonely Are the Brave. And the endings of our two films call attention to the doom of the cowboy in the modern world. Jack Burns is run down on the highway by a truckload of toilet bowls, driven by Carroll O’Connor (seeing retrospectively, we notice with a certain neatness how the worst features of the late twentieth century–Archie Bunker no less!–annihilate the idealism of the older world). And Hud, viewed through the eyes of Brandon de Wilde, whose eyes a decade earlier had watched Shane riding off into an illimitable distance, is left alone; his values are not really triumphant, for here it is the boy who rides into the future.

Lonely Are the Brave was released in June, 1962, Hud in May, 1963, and even the brief year between them was enough to give intimations of the future of both the society and the films that measure it. Lonely Are the Brave really belongs to the Age of Eisenhower. Our sympathies are ultimately enlisted on the side of the reluctant and rather inept sheriff played by Walter Mathau. We regret the passing of the cowboy, but grasp its inevitability; Matthau is allowed to say the valedictory at the end. The values of a society, however disagreeably represented by jet planes overhead, cars flashing by, and “no trespassing” signs, prevail, and we see the propriety of their prevailing. Though “the Sixties” properly began with the assassination of John Kennedy, Hud, appearing six months before, shows signs of social values unravelling. The most memorable scene in the picture is the rounding up of the cattle afflicted with foot-in-mouth disease, and the wholesale shooting of them as they crowd into a trench in the ground. While this scene recalls two earlier set pieces of mass extermination of animals, in Fenimore Cooper’s novel The Pioneers, and Renoir’s film The Rules of the Game, both symbolic of the passage of an older, more civilized order, it goes one step further by underlining the malevolence of this society, and even associates Hud with it, for he has used its machinery to declare his father incompetent. Only the boy gives us much hope for the future, and this hope is undercut by Hud’s final statement that there is “so much crap” in the world, in which he Lon, will have to wallow sooner or later. His image calls back the trench with its dying herds, reminiscent as well, as Ritt has acknowledged, of the dark stain laid on human values by the slaughter of the death camps under the Nazis.

Both films were well received by the critics, though Lonely Are the Brave was not a popular success; it acquired a certain “relevance” in “The Sixties,” when youthful audiences identified, rather more than they were supposed to, with the cowboy. Hud was labelled “a near miss” by Variety, who found it too abstract, its thesis insufficiently filtered through its characters. But Bosley Crowther liked it (“this year’s most powerful film”), and the Academy hailed it as well, nominating it for seven Oscars, and giving it three, for Best Actress (Patricia Neal), Best Supporting Actor (Melvyn Douglas), and Best Cinematography (the veteran James Wong Howe). Newman was nominated for the second time of seven, having been nominated two years before for the role of Fast Eddie in The Hustler, the reprise of which role in The Color of Money finally brought him the Best Actor award this year; in 1963 he lost out to Sidney Poitier in Lilies of the Field.

Though these two films are both actor’s films, with Lonely Are the Brave produced by its star, and Hud more the product of a collective than Ritt’s pictures, even with the Ravetches and Newman, usually are, it is the more surprising that Dalton Trumbo’s script does not assert itself more in Lonely Are the Brave. Trumbo was the first to emerge of the Hollywood Ten, and after winning an Oscar pseudonymously in 1956 had been billed for the first time under his own name–under Douglas’s wing-in Spartacus, the year before Hud. Such sympathy, anti-socially based, as we feel for Jack Burns must owe a lot to Trumbo.

Notes by Barrie Hayne

Leave a Reply