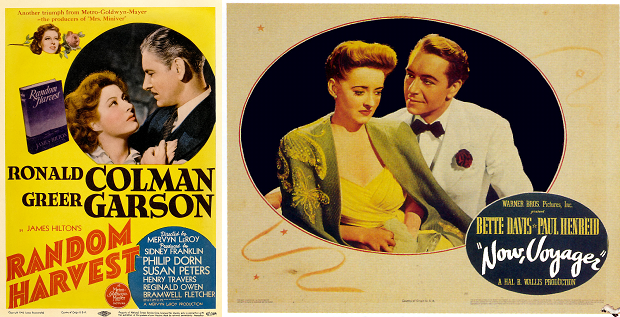

Random Harvest (1942) and Now,Voyager (1942)

Toronto Film Society presented Random Harvest (1942) on Sunday, September 27, 1981 in a double bill with Now, Voyager (1942) as part of the Season 34 Sunday Afternoon Film Buffs Series, Programme 1.

Random Harvest (1942)

Production Company: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Producer: Sidney Franklin. Director: Mervyn LeRoy. Screenplay: Claudine West, George Froeschel and Arthur Wimperis, based on the novel by James Hilton. Photography: Joseph Ruttenberg. Music: Herbert Stothart. Art Direction: Cedric Gibbons.

Cast: Ronald Colman (Charles Rainier), Greer Garson (Paula), Philip Dorn (Dr. Jonathan Benet), Susan Peters (Kitty), Henry Travers (Dr. Sims), Reginald Owen (“Biffer”), Bramwell Fletcher (Harrison), Rhys Williams (Sam), Una O’Connor (Tobacconist), Charles Waldron (Mr. Lloyd), Elizabeth Risdon (Mrs. Lloyd), Melville Cooper (George), Margaret Wycherly (Mrs. Deventer), Aubrey Mather (Sheldon), Arthur Margetson (Chetwynd), Alan Napier (Julian), Jill Emond (Lydia), Marta Linden (Jill), Ann Richards (Bridget), Norma Varden (Julia), David Cavendish (Henry Chilcet), Ivan Simpson (The Vicar), Marie De Becker (Vicar’s Wife).

Now, Voyager (1942)

Production Company: Warner Brothers. Producer: Hal B. Wallis. Director: Irving Rapper. Screenplay: Casey Robinson, based on the novel by Olive Higgins Prouty. Photography: Sol Polito. Music: Max Steiner. Them Song: “It Can’t Be Wrong” (lyrics by Kim Gannon).

Cast: Bette Davis (Charlotte Vale), Paul Henreid (Jerry Durrance), Claude Rains (Dr. Jacquith), Gladys Cooper (Mrs. Henry Windle Vale), Bonita Granville (June Vale), Ilka Chase (Lisa Vale), John Loder (Elliot Livingston), Lee Patrick (Deb McIntyre), Franklin Pangborn (Mr. Thompson), Katherine Alexander (Miss Trask), James Rennie (Frank McIntyre), Mary Wickes (Dora Pickford), Janis Wilson (Tina Durrance), Michael Ames (Dr. Dan Regan), Frank Puglia (Manoel), Charles Drake (Leslie Trotter).

After the Christmas thing was over, the goddam picture started. It was so putrid I couldn’t take my eyes off it. It was about this English guy, Alec something, that was in the war and loses his memory in the hospital and all. He comes out of the hospital carrying a cane and limping all over the place, all over London, not knowing who the hell he is. He’s really a duke, but he doesn’t know it. Then he meets this nice, homey, sincere girl getting on a bus. . . .But then, one day, some kids are playing cricket ball. Then right away he gets his goddam memory back. . . and he forgets all about the homey babe that has the publishing business. . . .Anyway, it ends up with Alec and the homey babe getting married, and the brother that’s a drunkard gets his nerves back and operates on Alex’s mother so she can see again, and then the drunken brother and old Marcia go for each other. . . .All I can say is, don’t see it if you don’t want to puke all over yourself.

J.D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye (1951)

The film that Holden Caulfield saw on that memorable December afternoon in Radio City Music Hall represents a pastiche of the type of film that Hollywood made and remade with superb assurance through much of the Depression and the War that followed–glossy, lachrymose stories of intricate plot, turning the screws of suffering upon their female protagonists. Duration, usually of some years, is essential, for brief suffering is of little interest, and renunciation is almost the sine qua non. Typical directors are John Stahl, Leo McCarey, George Stevens, and Mervyn LeRoy, using the novels of Fannie Hurst, Lloyd C. Douglas, and James Hilton, and a typical list of such films would include Back Street (1932 and 1941), Imitation of Life, Magnificent Obsession (1935), Stella Dallas (1937), Intermezzo, When Tomorrow Comes, Love Affair, Penny Serenade, The Great Lie, In This Our Life, and–the two films we see this afternoon. Salinger’s parody draws heavily upon Magnificent Obsession, and even more heavily upon Random Harvest itself, which in fact opened at the Music Hall in Christmas week 1942, and ran–still a record–for twelve weeks in that enormous theatre. Two months earlier the New York Times had dismissed Now, Voyager as “Bette Davis’ latest tribulation. . . . two lachrymose hours,” and it now turned up its nose at Random Harvest: “for all its emotional excess, . . .a strangely empty film.”

Yet when Robert Mulligan took the adolescent characters of Summer of ’42 (1971) to the pictures in that first year of the War, what did they see but Now, Voyager? The New York Times, Holden Caulfield, and most film critics aside, how does one account for the great–and continuing–appeal of these romantic melodramas, forty or fifty years old? That the immediate vogue of such films was past by the 1950s is suggested both by Holden’s remarks and by Douglas Sirk’s mordant and cynical remakes of two of the most famous of them (Magnificent Obsession and Imitation of Life). Certainly the genre was well suited to offsetting the woes of the ‘thirties and ‘forties. It is, surely, the other side of screwball comedy, perhaps symbolized by Colman’s appearance, this same year, in The Talk of the Town, and by Davis’s in The Man Who Came to Dinner. The screwball comedies enabled the Depression audience to laugh its troubles away at the antics of the rich; these melodramas enabled them to cry, while noticing that the rich might be worse off than they. We may be poor, afflicted by a great war, but isn’t Charles Rainier less fortunate, maimed by the great war, and living an empty life, with his very identity lost to him? Surely our lives are not as barren as the mother-dominated Charlotte Vale’s? And the end of each film gives us the best of both worlds: Charles (or Smithy) goes back to his true love, presumably retaining still his manorial estates; Charlotte and Jerry have a great, if limited, affair to remember–the stars if not the moon.

Both these films are based on strong melodramas by strongly sentimental novelists: James Hilton gave at least five romantic blockbusters to the American cinema, including Lost Horizon and Goodbye Mr Chips, and he wrote the screenplay for Mrs Miniver; and Olive Higgins Prouty wrote as well the novel from which Stella Dallas was adapted (Hilton liked the film version of his Random Harvest so well that he volunteered to speak the opening narration).

Both films, moreover, are directed by strongly sentimental artisans of the studio system: Random Harvest by Mervyn LeRoy, whose other films in this genre include Waterloo Bridge, Blossoms in the Dust, and the 1949 remake of Little Women; Now, Voyager by Irving Rapper, whose first important film this was, and who went on to direct The Corn is Green, The Voice of the Turtle, The Glass Menagerie, and Marjorie Morningstar.

But the greatest strength of the two films probably lies in their line-up of players, another product of the more disciplined studio system of forty years ago. What would an M-G-M picture of those years be worth without Reginald Owen, or a Warners without Franklin Pangborn? The acting strength holds down to the briefest walk-on parts: to Peter Lawford in Random Harvest, his career still before him; to Frank Puglia, an old D.W. Griffith regular, and Tempe Pigott, of many a silent film, their careers largely behind them.

And then there are the stars! In Random Harvest, Ronald Colman, who had begun his career playing opposite Lillian Gish in The White Sister twenty years before, and who still had an Academy Award before him in A Double Life, is joined by Greer Garson, who had sprung into the first rank of Hollywood’s leading ladies with Goodbye Mr Chips three years before, and was already pidgeon-holed with Blossoms in the Dust and Mrs Miniver. The lovely young Susan Peters should be mentioned; on the threshold here, she would soon be felled by a spinal injury, making her last film in a wheelchair, and dead at thirty. In Now, Voyager, Bette Davis, at the pinnacle of Hollywood in 1942, the year Garbo abdicated, Carole Lombard died, and her only other rivals, Crawford and Marlene, saw their careers in temporary decline (They All Kissed the Bride and The Spoilers). Opposite Davis is Paul Henreid, who had made his American debut with Greer Garson in Goodbye Mr Chips, and would play his most famous role this same year of 1942: how many stars have had two such parts as Jerry Durrance and Victor Laszlo within so brief a space? Unless perhaps Claude Rains, who had three such in 1942: with Henreid in Casablanca and Now, Voyager, and in King’s Row. And between these stars and the walk-ons, a minor galaxy: Philip Dorn, John Loder, Gladys Cooper, Melville Cooper, Una O’Connor, Alan Napier.

Backing up the more visible talents are, again, the teams who gave the studio system its reason for being. Perhaps most important, in these two very glossy films, are the cinematographers: Joseph Ruttenberg, who won Oscars for The Great Waltz, Mrs Miniver, Somebody Up There Likes Me, and Gigi, photographed Random Harvest; and Sol Polito, one of Warners’ very best cameramen of the ’30s and 40s (42nd Street, Angels With Dirty Faces, Adventures of Robin Hood, Sergeant York) photographed Now, Voyager.

Finally, these two pictures must be seen as deriving their excellence as great popular artifacts from the best features of the studio and star systems. It may, however, still be beyond analysis to separate their undeniably moving qualities from their no less undeniably trashy ones. Ultimately we may just have to sit and watch them, suspending our critical disbelief while admiring their production values and their actors’ performances. Let’s not reach for the moon when we already have the stars!

Notes by Barrie Hayne

Leave a Reply