Robin Hood (1922)

Toronto Film Society presented Robin Hood (1922) on Monday, December 3, 1956 as part of the Season 9 Monday Evening Silent Film Series, Programme 3.

Robin Hood (USA 1922) Produced by Fairbanks-United Artists. Directed by Allan Dwan. Scenario by Lotta Woods, based on Alfred Noyes’ poem. Story by Elton Thomas ( Douglas Fairbanks). Settings: Irvin J. Martin. Design: Wilfred Buckland. Photographed by Arthur Edeson.

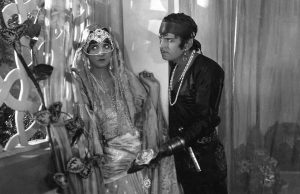

Cast: Douglas Fairbanks (Earl of Huntington); Enid Bennett (Maid Marian); Wallace Beery (Richard I); Sam de Grasse (Prince John); Willard Louis (Friar Tuck); Alan Hale (Little John); Maine Geary (Will Scarlett); Lloyd Talman (Alan-a-Dale); Paul Dickey (Sir Guy of Gisborne).

“Serving the yearning for escape into dream worlds in the early 20’s”, says Lewis Jacobs in the Rise of the American Film, “were the sentimental and nostalgic adventure tales of by-gone days. Douglas Fairbanks reached the high peak in his career as a swashbuckling hero in The Thief of Bagdad, Robin Hood, The Mark of Zorro and The Three Musketeers.”

A few vital statistics from the Museum of Modern Art’s notes on the film: “When the profits of his Three Musketeers were counted, Fairbanks saw himself for the first time as an impresario. He warmed to the risk entailed in staking his entire fortune on a new and grandiose film, Robin Hood. He started his vast project by taking 3000 actors off relief, giving them their meals and $7.50 a day. He placed the contract for the towering 200 feet of construction which was to be Nottingham Castle. On a steel structure that looked like a draft for Boulder Dam, synthetic masonry was overlaid; an army of painters aged it; landscape gardeners bound it with ivy. This construction job did not, however, involve strangulation of the Fairbanks character by drapes and decor. The decor was still a background and did not impede the flying figure of the hero. It must have been impossible for Fairbanks then, fired by a new sort of grandeur and a new career–that of showman extraordinary to the film business–to guess the moment when costume and romantic trappings would overwhelm his own acting, shackle the free-moving domain of the happy athlete. It subsequently appeared that at the premiere of Robin Hood in November 1922, he was at the exact peak of his popularity.”

Rene Clair, in March 1923 said of the movie: “Robin Hood seems quite undaunted by the tremendous reputation which preceded it. A film like this disarms the critic. How can he argue about details, faced by such a whole? I do not know if the middle ages as seen by Americans are the real middle ages. Costumes and castles do not suffice to show us an epoch. We ought to be shown its spirit as well. As this cannot be done, I like Fairbanks’ version quite as much as the allegedly exact accounts in history books. What in this film deserves our unreserved praise is its movement. People accustomed to the conventions of theatre do not understand this, and Robin Hood for them is just childish nonsense on a huge scale. But you must ignore the plot. Judge Robin Hood as you would a ballet or pantomime. Look at it with simple eyes. Watch the perfection of the movements, the whole of its movement; cinema was created in order to record that. For me, Robin Hood is an army of blazing oriflammes on the march, the galloping of iron horses, a dance of free men in a forest, a race in a giant’s castle, leaps across the void, woods, rivers and fields–would you say Victor Hugo’s Legende des Siecles is any closer to reality? It is neither more exact nor more lyrical. All the improbabilities, the prodigious exploits we expect in Fairbanks’ films are here completely justified, and in perfect harmony with the whole spirit of the film. The main quality of Hugo’s epic is undoubtedly its rhythm. The same applies to Fairbanks’ work. The rhythm of Robin Hood makes one forget its imperfections. I am aware that the whole comparison is very trite but I hope it may help me to convince some ‘intellectuals’ that a film like this can have as great value as a poem, and that it is as futile to pick out the improbabilities in one as in the other. Lyrical movement covers all their faults. Of course one may not like La Legende des Siecles. I don’t say I read it once a week. And frankly, compared with some of its more pompous passages, I prefer Robin Hood, which may be more naive but is certainly more entertaining.”

Paul Rotha in The Film Till Now says of “Doug”: “It may seem ridiculous to claim that Fairbanks, an acrobat who is unable to put drama into his gestures or emotion into his expressions, is one of the outstanding figures in the world of the cinema. Yet by reason of his rhythm, his graceful and perpetual motion, he is essentially filmic. He has, it is true, no other talent than his rhythm and his ever-present sense of pantomime, except perhaps his superior idea of showmanship. He sees in every situation of the past and the present a foundation for rhythmical movement–learning to fence, crack a whip, throw a lariat, he saw in these accomplishments some basis for filmic movement other than mere acrobatics. He realized that the actions were superbly graceful in their natural perfection, as indeed are any gestures born out of utility. He delights equally in the swing of a cloak, the fall of the ostrich feather in his hat, the mounting of his horse, the hang of his sword. In all his costume pictures Fairbanks took the utmost pleasure in the romanticism the clothes of the period offered him. Though none of his films has been nominally directed by him, he is the underlying mind behind very detail however small. The spirit of Fairbanks is at the base of every factor in his productions; behind every movement, the design of the sets, the choice of the cast, the layout of the continuity, the making of the costumes, the technical perfection of camerawork and lighting.”

Perhaps Allan Dwan, the director of Robin Hood, deserves more credit than the above would suggest. In Douglas Fairbanks, The Fourth Musketeer, his niece Letitia says: “Much of the ease and grace with which Doug performed his stunts in Robin Hood and previous pictures was due to Allan Dwan’s coaching”–and claims that Doug had been reluctant to do Robin Hood until persuaded by Dwan.

The latter, though he has never made a distinguished film, is a veteran of many years’ standing who, in this silent era, was well-known as a director of famous stars (Fairbanks, Gloria Swanson, etc.) in box-office successes. He still makes acceptable action “program pictures” today.

Leave a Reply